YASNAYA POLYANA, Tula Region — When they were in their 50s, Elaine and Alfred Podovinikoff packed up their lives in their native Canada and emigrated to a muddy, provincial Russian settlement with a single paved road and freely roaming chickens.

The Podovinikoffs resettled just south of Tula — an industrial city of half a million known for its gingerbread, samovars and weapons factory — in Yasnaya Polyana, the ancestral estate of revered writer Leo Tolstoy. The white and emerald house that Tolstoy shared with his family can be seen from their back porch.

It was the connection with Tolstoy that brought Elaine and Alfred — third and fourth generation descendants of Russia's Doukhobors, a sectarian Christian denomination that was persecuted under the Russian Empire — to Yasnaya Polyana from the city of Grand Forks, British Columbia. After all, it was thanks to the great Russian writer that their ancestors found refuge in Canada.

"There is something enchanting in Yasnaya Polyana, because Tolstoy lived here," said Alfred, a 69-year-old retired teacher specialized in industrial education. "And he was the one who helped the Doukhobors."

The Doukhobors emerged in the 18th century in protest against practices of the Russian Orthodox Church. The group's name is believed to have been coined by Archbishop Ambrosius of Moscow, who in 1785 dubbed its members "Dukhobortsy," which literally means "spirit wrestlers." The Orthodox Church viewed them as being at odds with the Holy Spirit. The Doukhobors accepted the name but gave it their own interpretation: They would "wrestle" injustice with the strength of their spirit, and not with force.

The Doukhobors lived simply, rejected icons and the Bible as literal teaching, and believed that God dwells in every human being. As firm pacifists, they refused to fight for the tsar, despite decrees in the 1820s that forced them into conscription and to adopt Orthodox Christianity.

Conscientious objectors were not welcome in tsarist Russia. Doukhobors were persecuted on a vast scale and most of their population, which totaled several thousand, were exiled to the Caucasus and Siberia.

Kindred Spirits

Upon hearing of the Doukhobors' hardships in 1894, Tolstoy became intrigued by their communal lifestyle, pacifism and rejection of the Oxthodox Church's institutions. The Doukhobors' philosophy, he realized, was similar to his own.

"The Doukhobors have been subjected to floggings, incarcerations and all kinds of tortures in disciplinary battalions, from which many have died," Tolstoy wrote in an appeal to raise awareness about their plight in 1898.

"They have asked me to help them, and so I consider it my duty to address all good people, both of Russian and of European society, asking them to help the Doukhobors get out of the painful situation in which they now find themselves."

Tolstoy reportedly donated $17,000 of his earnings from his last novel, "Resurrection," to resettle the Doukhobors in Canada. Elaine and Alfred's families were among those that benefitted from Tolstoy's largesse.

"Tolstoy and the Doukhobors had a symbiotic relationship," said Andrew Donskov, a Tolstoy scholar at the University of Ottawa. "The Doukhobors needed help from Tolstoy to leave Russia, and Tolstoy — who was very pragmatic — needed the Doukhobors to serve as an example of his teachings."

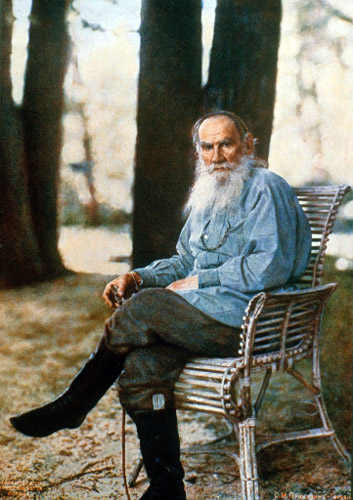

Leo Tolstoy at Yasnaya Polyana.

Exodus to the Promised Land

In 1899, nearly 7,500 of the Caucasus Doukhobors — a third of the community — emigrated to Canada. Tolstoy's eldest son, Sergei, accompanied 2,300 of them on the 23-day trans-Atlantic journey to Halifax. The Doukhobors then made their way to the central and western provinces of Saskatchewan, Alberta and British Columbia.

Today there are between 30,000 and 40,000 people of Doukhobor descent in Canada, according to the country's federal library and archives. In the 2011 Canadian census, 2,290 individuals described their faith as "Doukhobor." Canada's Doukhobors are integrated into society but maintain their traditions through Russian-language spiritual songs.

Elaine and Alfred grew up reading and writing Russian, and after 14 years here, are now fluent in the language, though their foreign roots are audible in their speech. Elaine, 67, said she is sometimes taken for a Ukrainian.

"My dad would always say, 'Po-russki, po-russki!' ('Say it in Russian, in Russian!')," said Elaine, who runs two English-language playschools in Moscow. "We were always encouraged to speak Russian. Language was part of how we keep our traditions alive."

They visited the Soviet Union for the first time in 1969, and Elaine, who taught Russian in Canada, made three trips to the country with her students in the 1990s.

A New Life

The Podovinikoffs had a good life in Canada: a loving family, a supportive community and occupations they loved. But the comfort of Canada, to which they return at least once a year, left them longing for something more.

"I realized something was missing in my life in Canada," Elaine said. "My Russian soul was not attached there. And you can't get away from a Russian soul."

"The Doukhobors built railroads and granaries in Canada, but I still felt a bit like a foreigner there," Alfred said. "When I came back here, to Russia, I really felt at home. I lived half of my life in Canada. Why not live the other half here?"

Their three children, who all grew up in Canada, moved to Russia after completing their university education. They settled in Moscow starting in the mid-1990s, fulfilling their desire to see the world and seek out their ancestors' lifestyle. Six of Elaine and Alfred's nine grandchildren also currently live in Russia.

"We took a year off from work in 2000 to visit our children here," Elaine said. "And we just kept on staying. There was no convincing to be done."

Starting Anew

Upon settling in Russia, Elaine worked at the British International School in Moscow, while Alfred put his Canadian experience to use in a Russian construction company. It was not long before Elaine established her own institution.

In 2006, the family opened English-language playschools called "Our Children, Our School" in two locations in southeastern Moscow. Now semi-retired, Elaine commutes to Moscow three times a week to oversee work being done at the schools. She hopes to establish another English school in Tula, where students could study the language for free.

For several years, the Podovinikoffs split their time between Moscow and Tula, which they used as a base to build their home at the heart of Tolstoy's birthplace, Yasnaya Polyana.

"In 2007, we rented an small apartment in Tula and commuted from there while we were working on our house," Elaine said. "We started with an unfinished building that had to be knocked down, and we turned it into a complete home two years ago."

The couple, who said they have many Russian friends of all beliefs, asserted that they have not been discriminated against or ostracized since their return to Russia, despite the public prominence of the Orthodox Church, the same institution that drove their ancestors away.

Alfred recalled only one incident. Many years ago, an Orthodox priest called him "sinful" for being a Doukhobor.

"I am not sinful," he answered the priest. "The sinful are those who teach our young how to kill and those who bless them."

And with that, Alfred did what any Doukhobor would do: He continued on his way.

Contact the author at g.tetraultfarber@imedia.ru

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.