Since Vladimir Putin has held the reins of the Russian leadership, Russia has actively integrated into the global economy, making the era of his rule even more liberal in an economic respect than it was under former President Boris Yeltsin. Russia ranked seventh in the world for stock market capitalization at the time of the 2008 crisis, foreign assets in its banking system reached 26 percent, and foreign trade increased by almost five times from 2000 to 2008.

The number of Russians traveling abroad rose from 9.8 million in 2000 to 32.7 million in 2008, and Russia's rate of development in modern communications and various segments of the Internet economy was one of the fastest in the world.

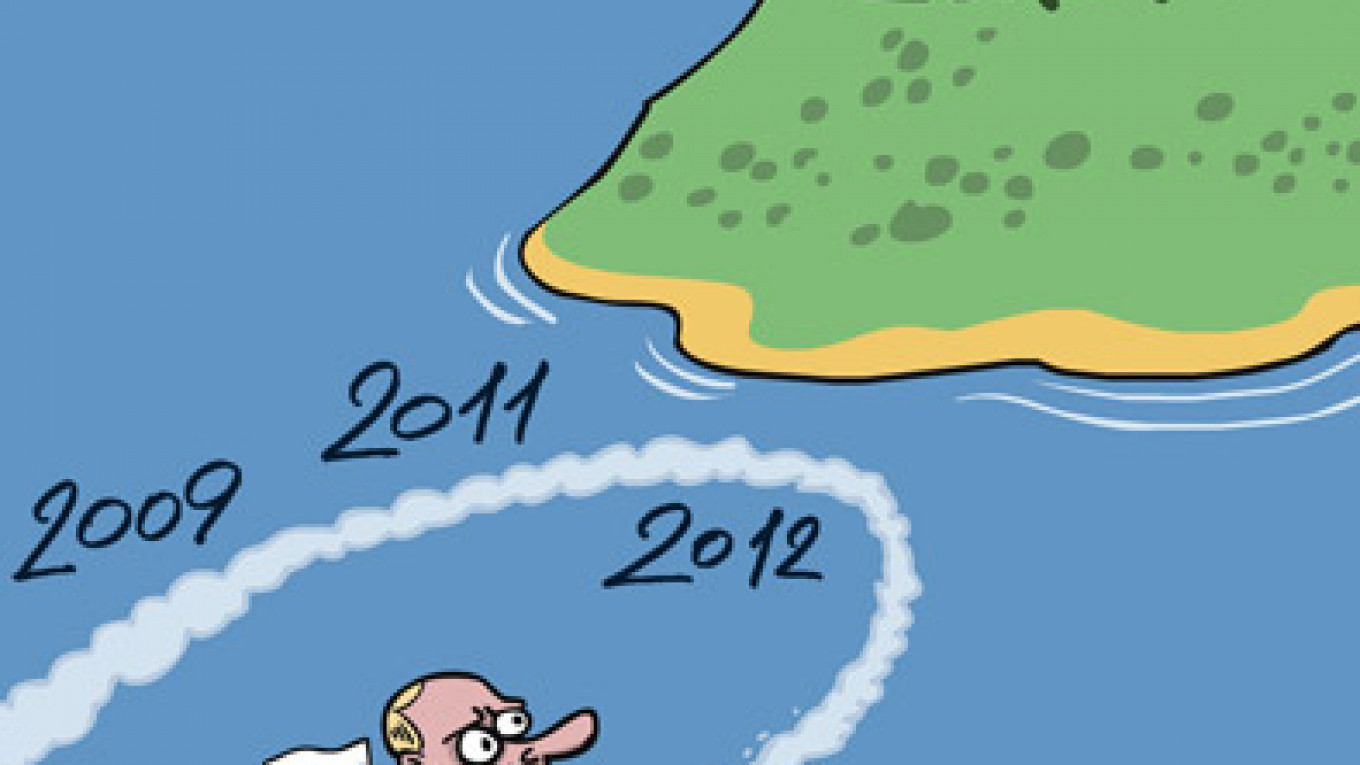

But the situation began to change in 2011 when two important circumstances became clear. On one hand, the relative success of the Russian economy gave rise to a call for political change, and many anticipated a "new perestroika" under the more progressive and tech-savvy President Dmitry Medvedev.

On the other hand, it became evident that Russia lacked the mobilization and technological capacity to achieve large-scale modernization and end the country's reliance on natural resource exports in the near future.

That began Russia's "reversal of 2012" — the point at which the political elite understood that a gas and oil economy worked best under a nondemocratic "power vertical" and that restructuring the country's political foundations in hopes of achieving an uncertain result — and at a time when mass public protests were on the rise — was simply too risky.

Russia began turning away from Europe, and the West as a whole, not during the Ukrainian revolution in February, but when Putin began his third term as president in 2012. The fact that many Western leaders in recent years had what Polish President Bronislaw Komorowski called "hopes for Russia's democratic modernization" only proves that they misunderstood the nature and outlook of the Russian elite and people.

By 2014, Russia had once again become a country whose leadership showed no intention of complying with the rules of foreign or domestic policy. In fact, those leaders would probably act even more decisively if economic considerations did not hold them back. But the truth is that Russia depends heavily on the world economy, even if its political elite believe otherwise.

That is the reason observers hold little hope for a "return to normalcy" for the Russian economy. The convulsive turn that Russia took between March and August 2014 could lead to disastrous economic losses in the near future. Investment is expected to fall by 10 to 15 percent in 2015, personal incomes will gradually begin to fall and the government's "major projects" will either proceed at a crawl or stop altogether.

Hardships will hit Russia's private businesses hardest, even while the government continues pumping budgetary funds into bailouts for state-owned corporations headed by Putin's close associates. And yet, private businesses will ultimately suffer even more from retaliatory measures taken by the Russian government and by the actions of state-owned corporations that are jacking up prices for their services and reducing market liquidity.

Over the next few years, Russia will also fail to benefit in almost any way from its "turn toward the East." The failure of that project will grow increasingly evident just as anti-Western sentiment in Russia declines, giving way once again to envy of Western prosperity and a desire for renewed friendship.

Russia cannot survive without the outside world. The external debts of its banks and corporations exceed the size of its foreign exchange reserves. Russia finances more than half of its budget with the export of raw materials and imports 100 percent of its computers, mobile communications devices, telecommunications technology and many types of equipment. Under such conditions, the economy itself will have an impact on the country's political course.

Many people raise the objection that the process of globalization in the early 20th century did not prevent the outbreak of World War I. That is true, but 100 years ago European powers were constantly fighting either each other or in their colonies, human life meant less, and war seemed like a perfectly appropriate means for solving many problems.

Today nobody is prepared to give their life for the sake of Gazprom or Rosneft, and most citizens and politicians understand that it is no longer possible to solve serious problems through direct confrontation. Russia's "foreign offensive" will fail not because of a defeat at the front, but for lack of support at the rear. And the more actively Russia isolates itself from the international system, the sooner that mutiny will occur.

The Russian reversal that occurred between 2012 and 2014 is a dead-end maneuver that robs the country of any way to operate in a rational and constructive way. Under such circumstances, the West should adopt a very cautious approach to provoking Russia. There is no need to cut off Russia from the SWIFT money-transfer system: Just threaten to do so several times, and Moscow will quickly jerry-rig its own closed network.

No need for the West to block the Russian segment of the Internet: Washington need only remind Moscow of its "information vulnerability," and Russia will cut itself off from the world post haste. The only way to stop Russia's "convulsive turn" is to show the Russian people that their own leaders carry far more responsibility for the country's problems and failures than any perceived enemies in the West.

No further sanctions are even necessary: Those already in effect are enough to prod Moscow leaders into taking retaliatory measures that will derail Russia's economy.

And when that happens, Russia will turn once again to the West — as it has turned many times in the past — in search of investment, technology and innovation. At that point, both sides will need to build economic and political ties that are strong enough to resist the machinations and adventurism of a handful of oligarchs with close ties to the Kremlin.

Vladislav Inozemtsev is a professor of economics at the Higher School of Economics and director of the Moscow-based Center for Post-Industrial Studies.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.