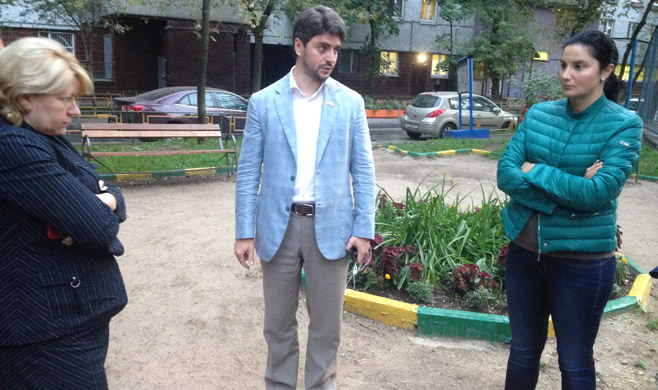

A pint-sized lapdog runs laps around the voters mingling with Moscow legislature candidate Igor Sviridov in the darkening gloom of a local playground, as a child chases after it.

The grownups try their hardest to go on talking about playground equipment and the alcoholics who occupy it, but eventually crack a smile at the dog or stoop down to pet it. No one notices the child.

All of which looks like a metaphor for the Moscow elections, one of 5,800 local votes set to take place across 84 of Russia's 85 regions on Sunday. A third of the governor corps faces reelection, with most incumbents slated to win, and 14 regional legislatures will be up for grabs.

Like most local elections, this round will be desperately dull to people outside of the cities and municipalities affected — but it will provide a vital political read on a nation that has recently sent the world into a state of political shock.

The read is not good: Most opposition candidates have been carefully weeded out, leaving the loyalists to compete or act as extras to the ruling establishment's unchallenged nominees.

Rules of electoral engagement will, admittedly, change and change again before the more influential federal parliamentary elections of 2016 or the presidential vote of 2018.

What is more strategically important is that the regional elections are, in a democracy, meant to serve as an incubator for budding political elites.

And it remains to be seen whether this season's elite hopefuls are political children awaiting a growth spurt, or lapdogs who will never get any bigger.

"Any election is useful: Even in Soviet times, with a single candidate on the ballots, the votes were a good exercise for developing political skills," regional expert Alexei Titkov said Thursday.

"And these days, we're at least more open than back then," Titkov, a professor at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow, said with reserved optimism.

City Duma hopeful Barbara Babich

The Latest in Vote Fraud

Ever since Russia allowed multiple parties in 1989, electoral fraud has been recognized as an inevitability.

Outright vote-rigging fell out of fashion after the mass protests of 2011-2013 and mathematicians pointing out that official voting results in Russia routinely defy the basic rules of statistics.

But the political arsenal in Russia still has many tricks, some home-grown and others seemingly taken straight out of the American book of 1930's vote meddling.

There is the multifaceted "administrative resource," when people in power running for reelection or new job milk their positions of authority for promotion.

Rank-and-file state employees are reportedly forced or coerced to vote for or promote candidates, who also enjoy sympathetic blanket coverage of their daily toil in mostly state-run local media.

There are spoiler and "technical" candidates, who serve primarily to distract the public by turning the vote into a sort of a pro-wrestling match: kitschy, entertaining and scripted.

Russia's top spoiler is Sergei "Spider" Troitsky, an inane heavy metal icon who pops up periodically on ballots across the nation, riding high on a platform of booze, gratuitous sex and general debauchery.

Troitsky is sitting out this round of elections, but in his place, the Moscow ballots will feature one Barbara Babich, 23, an unemployed theater college graduate and passionate football fan with impressively deep cleavage.

Bosom aside, Babich gained notoriety on the strength of her social network posts, which attest to a love of violence and vodka, and a loathing of romance and rival football fans, who are invited to "suck off."

She outlined in emailed comments a sensible political agenda focusing on youth problems, complete with boosting the efficiency of budget spending in the area, as well as applying unspecified "unorthodox methods" to get kids off the streets.

But her nonexistent campaign and reluctance to appear in public led many, The Moscow Times including, to suspect she may have been an ironic virtual entity, though she eventually confirmed her physical existence by appearing in televised debates.

A Curiously Selective Process

But the most efficient tool of political selection remains kicking candidates off the ballots on technicalities.

Candidates have to gather signatures in their support prior to being allowed on the ballots. Many flunk the procedure, as election authorities dub their signatures fakes or cite paperwork gripes less significant than a lapdog at a voter meeting — such as spelling the date as "'14" and not "2014."

Curiously, these problems affected candidates from the "non-systemic" opposition, many of whom have high public profiles and deployed dozens of signature collectors — but not many other candidates. Babich, a total unknown, had no problems collecting the requisite signatures.

"Their removal was a political decision," shrugged candidate Sviridov, who runs on the ticket of A Just Russia, a pro-Kremlin parliamentary party, and is thus spared the arduous task of collecting signatures.

"It's a shame, it would have been a much more interesting campaign otherwise," Sviridov, currently a district legislator in the capital, said in an interview on Wednesday night.

"And Moscow is still an isle of relative freedom compared to other regions," quipped Yury Korgunyuk, an expert on the Russian party system with the non-profit think-tank Indem.

Candidate Igor Sviridov mingling with his constituents in a playground Wednesday ahead of this weekend’s polls.

Lackeys or Democrats?

Speaking with The Moscow Times, a spin doctor working for a candidate in the upcoming elections classed the race's hopefuls into four categories, not counting the spoilers.

There are old political hands looking to keep their sinecures; doctors, teachers and other state employees whom the authorities asked to run to boost the legislature's public image; "systemic," or semi-loyal, members of the opposition; and up-and-coming careerists, the spin doctor said. He refused to go on the record because of his involvement in the campaign.

All of the above types will merge to shape up the regional elite, the manured ground from which federal-level politicians will spring, political analysts said.

But given the state of the regional electoral system, Russia should not expect too much from the politicians it is breeding, they said.

In a telling illustrations of the quality of the candidates, the incumbent head of the Moscow City Duma, Vladimir Platonov, was exposed as an alleged scientific plagiarist by Dissernet anti-plagiarism group earlier this week.

Another Kremlin-affiliated candidate in Moscow was accused of simply faking her Ph.D. diploma. Neither have commented on the allegations as of this article's publication.

In western Siberia, dozens of municipal votes had to be scrapped due to candidate shortages after most nominees were found to boast criminal records, which legislators are so longer allowed to have.

The vote still serves a valid purpose, because any electoral procedure promotes democracy, which is something Russians are still getting used to, said Titkov of the Higher School of Economics.

"But the ambitious see that the current system limits their career opportunities, and voters are alienated because they believe everything is decided without them," Titkov conceded.

Korgunyuk of Indem was more explicit in his diagnosis: "We're breeding clever, wily greasers who are only looking out for themselves," he said.

"All politicians are such, but ours are worse than usual," the expert said. "We're building an elite of lackeys."

Contact the author at a.eremenko@imedia.ru

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.