Originally published by EurasiaNet.org

Russia’s aggressive actions toward Ukraine are vexing Central Asian states.

First, officials in Kazakhstan were chagrined to hear comments by President Vladimir Putin, who, during a recent town hall-style meeting with university students, appeared to denigrate Kazakhstani statehood. Now, Uzbek leaders are showing signs of displeasure with Moscow.

Insular Uzbekistan has long viewed Russia with a wary eye: it has kept its distance from Moscow-led regional bodies and has shown no interest in joining the Eurasian Economic Union, Putin’s pet project to reassert Kremlin influence across the former Soviet Union.

The rhetoric currently coming out of Tashkent suggests that the conflict playing out in Ukraine has unsettled President Islam Karimov’s administration, and is prompting Uzbek officials to consider new steps to distance themselves further from the Kremlin.

During Independence Day celebrations on Sept. 1, Karimov pointedly denounced the tyranny of the Soviet past — and effectively thumbed his nose at Moscow. The “totalitarian” Soviet period, Karimov said, was a time of “oppressive injustice” and “humiliation and affront, when our national values, traditions, and customs were trampled upon.”

Karimov was harking back to the past, but given the battles raging in southeastern Ukraine, and with Putin making no secret of his ambition to expand Russia’s sway over former Soviet territory, the remarks were a clear sally at the Kremlin.

Karimov did not name Ukraine, but spoke of the need to prevent the escalation of conflicts into full-blown warfare in the current “alarming situation.” In comments clearly aimed at Russia, he went on to call for sovereignty and borders to be respected, and the use of force rejected.

Like other post-Soviet states, Uzbekistan has struggled to formulate a response to the Ukraine conflict, in large part because the Karimov administration finds neither side appealing. On one hand, Tashkent is leery of Kremlin expansionism; on the other, the dictatorial Karimov is no fan of popular uprisings, such as that embodied in the Euromaidan movement. Ukraine “has raised grave concerns [for Uzbekistan], precisely because each side has given the [Karimov] regime something to fear,” Alexander Cooley, a professor at New York’s Barnard College who specializes in Central Asian affairs, told EurasiaNet.org.

Until recently, Karimov’s government may have viewed Euromaidan as representing the larger threat to Uzbekistan’s status quo. But attitudes in Tashkent may be shifting.

“Revolutionary change of power seen in Ukraine is something that Uzbek authorities under Rresident Karimov have been tirelessly working to prevent in their country by effectively rooting out any potential pockets of political dissent,” Lilit Gevorgyan, a regional analyst at IHS Global Insight, told EurasiaNet.org.

“It is hard to see Uzbekistan cheering for the popular uprising in Ukraine,” she added, but “they are still likely to be critical, albeit not openly, of Russia's meddling in Ukraine.”

What Karimov is clearly apprehensive about is the Kremlin’s capacity to use soft power to undermine his long rule if he fails to toe Russia’s line, suggested Cooley.

“Tashkent is deeply concerned about the potency of Russian media and disinformation campaigns, as well as the potential political vulnerability of the status of millions of Uzbek [labor] migrants in Russia,” said Cooley. “They could be a lever for Moscow to bring Uzbekistan further in line with its position.”

Uzbekistan could face a destabilizing social crisis if Russia opted to expel Uzbek guest workers. Uzbekistan’s economy would be ill-equipped to absorb such a vast number of returning workers.

Russia’s assertion of a right to defend Russian speakers abroad is also viewed with trepidation in Tashkent, David Dalton, Uzbekistan analyst at the London-based Economist Intelligence Unit, told EurasiaNet.org.

“As with the other Central Asian countries that have a Russian minority, the Uzbek leadership, already wary of Russia's ambitions in the area, will have viewed with great alarm Russia's military intervention in Ukraine on the pretext of protecting Russian speakers,” he said. Uzbekistan does not share a border with Russia and has a relatively small ethnic Russian minority, comprising 5.5 percent of the country’s overall population of almost 29 million, but Kremlin policies still make Tashkent nervous.

The Kremlin’s muscle-flexing incentivizes Uzbekistan to boost other alliances, analysts believe. “It will emphasize Uzbekistan's need to diversify security and economic partnerships to the greatest extent possible,” Cooley said, mainly “through growing partnership with China, as well as economic partnerships with emerging Asian powers such as South Korea, Japan and the Gulf States.”

Tilting east is more promising for Tashkent than attempting to turn westward: partly since Uzbekistan’s geopolitical importance to the West is waning as NATO withdraws from Afghanistan; and partly since many Western states consider doing business with Karimov toxic due to Uzbekistan’s poor human rights record.

Western states, especially the U.S. and Britain, “remain constrained from increasing their engagement by political and human rights concerns, as well as the negative blowback they received from forging close security ties with Tashkent in the 2000s,” Cooley pointed out.

After 9/11, Washington wooed Uzbekistan — which sits on Afghanistan’s northern border — to open a military base, from which it was summarily ejected after criticizing the killing of protesters by Uzbek security forces in Andijan in 2005.

“Uzbekistan has tended to ‘turn West’ when it finds that Russia is becoming too assertive, and then back again to Russia when pressed too strongly by the West on its poor human rights record,” said Dalton. “This could happen again this time — although with most of its gas pipelines connecting with China, and Western forces pulling out from Afghanistan this year, it is not clear what Uzbekistan could offer the West in return.”

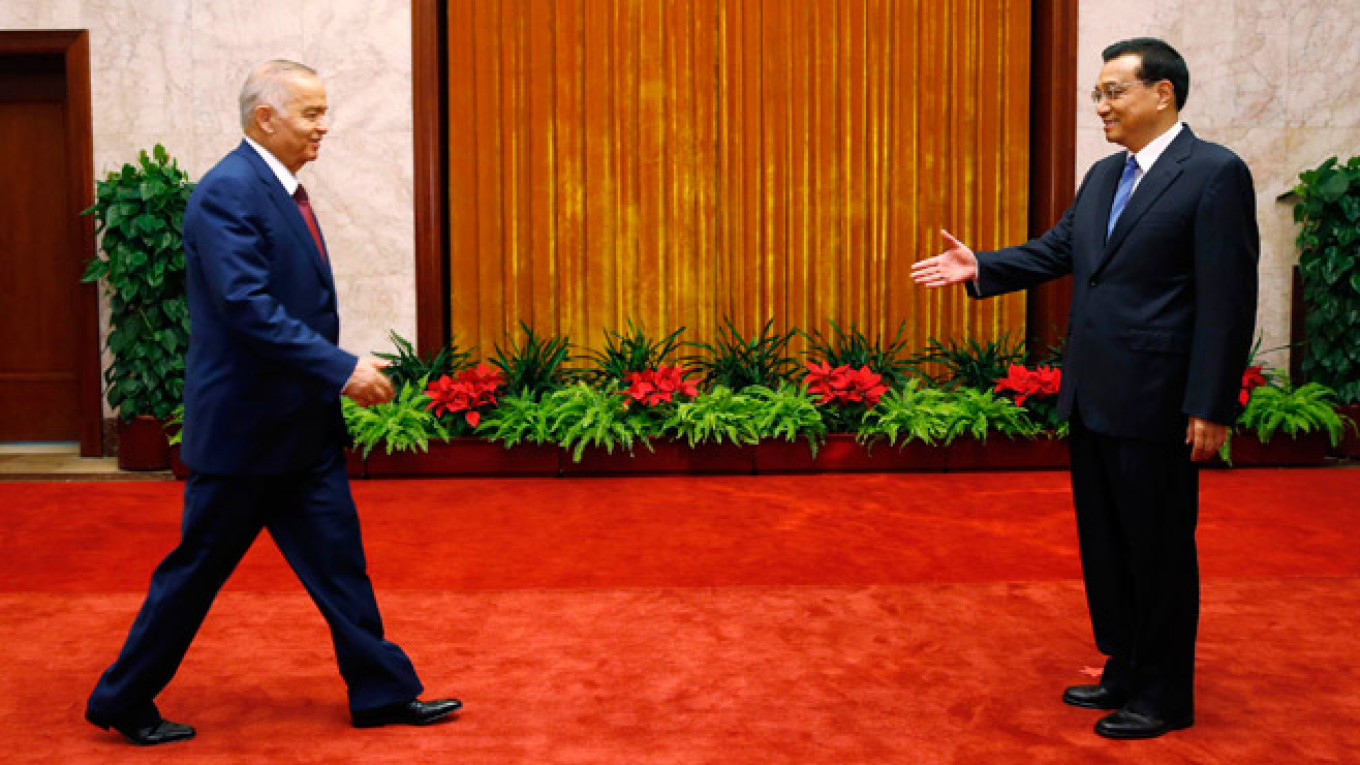

Ultimately, China — now a major purchaser of Uzbek gas — stands to benefit from Uzbekistan’s present dilemma. Karimov’s visit to Beijing in August was “an important signal,” said Dalton, “that Uzbekistan wishes to maintain good ties with strong foreign partners, to counterbalance Russian influence.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.