On the last day of summer, a Russian Orthodox priest imposed against his parishioners who had fought in Ukraine's "fratricidal war" a 20-year ban on receiving communion.

Those deemed to have only promoted the conflict raging in Ukraine's east, either verbally or in writing, will be hit with an 11-year ban, Father Grigory Mikhnov-Voitenko told his congregation in the small northern town of Staraya Russa.

Father Grigory is somewhat of an anomaly in the Russian Orthodox Church, which has remained surprisingly tight-lipped through the months of bloodshed in eastern Ukraine.

The silence is surprising, given the church's recent track record of vocal support for the Kremlin, which itself has endorsed the pro-Russian insurgents in Ukraine, who — for their part — are mostly radical conservatives claiming to be fighting in the name of God.

Ukraine has three separate Orthodox churches, only one of which — the Ukrainian Orthodox Church — is subordinate to Moscow. And the Moscow Patriarchate must remain on the fence if it wants to retain its already slippery grasp on that church, religious experts said Tuesday.

"If the Moscow patriarch is too pro-Moscow, then Moscow is all he'll be left with," quipped Maxim Goryunov, a prominent philosopher and acquaintance of Mikhnov-Voitenko.

"Of course, that may change because of pressure from the Kremlin," said Roman Lunkin of the independent pollster Sreda, which focuses on religious-themed surveys.

The Old PTSD Treatment

Mikhnov-Voitenko on Tuesday confirmed to The Moscow Times that he has denied the Eucharist to warmongers.

"It was a political statement," he said by telephone from Staraya Russa, an ancient town of 30,000 residents in the Novgorod region, the hotbed of medieval Russian democracy.

The cleric declined to elaborate, saying only that he had received "informal" feedback from the church leadership — of what kind, he would not say.

The Moscow Patriarchate had not publicly commented on Mikhnov-Voitenko's words as of Tuesday. Patriarchate spokesman Vladimir Legoida was unavailable to speak with The Moscow Times, while Alexander Volkov, a spokesman for church leader Patriarch Kirill, said he was unaware of the incident.

Mikhnov-Voitenko was technically within his right to ban his parishioners from communion, said Father Andrei Kurayev, a famous Orthodox missionary and informal spokesman for the church's liberal wing.

The Novgorod cleric based his decision on the writings of the famous fourth-century saint, Basil the Great. Kurayev confirmed these writings do, indeed, prescribe a temporary ban on the Eucharist for soldiers returning from war — which, he said, was "to mitigate the post-traumatic stress disorder."

Worry, Not Act

Kurayev declined to say whether Mikhnov-Voitenko's ban was an indication of the inner feelings of the Russian clergy, or whether he had gone against the grain by denouncing what many in Russia see as their compatriots' struggle for freedom in Ukraine.

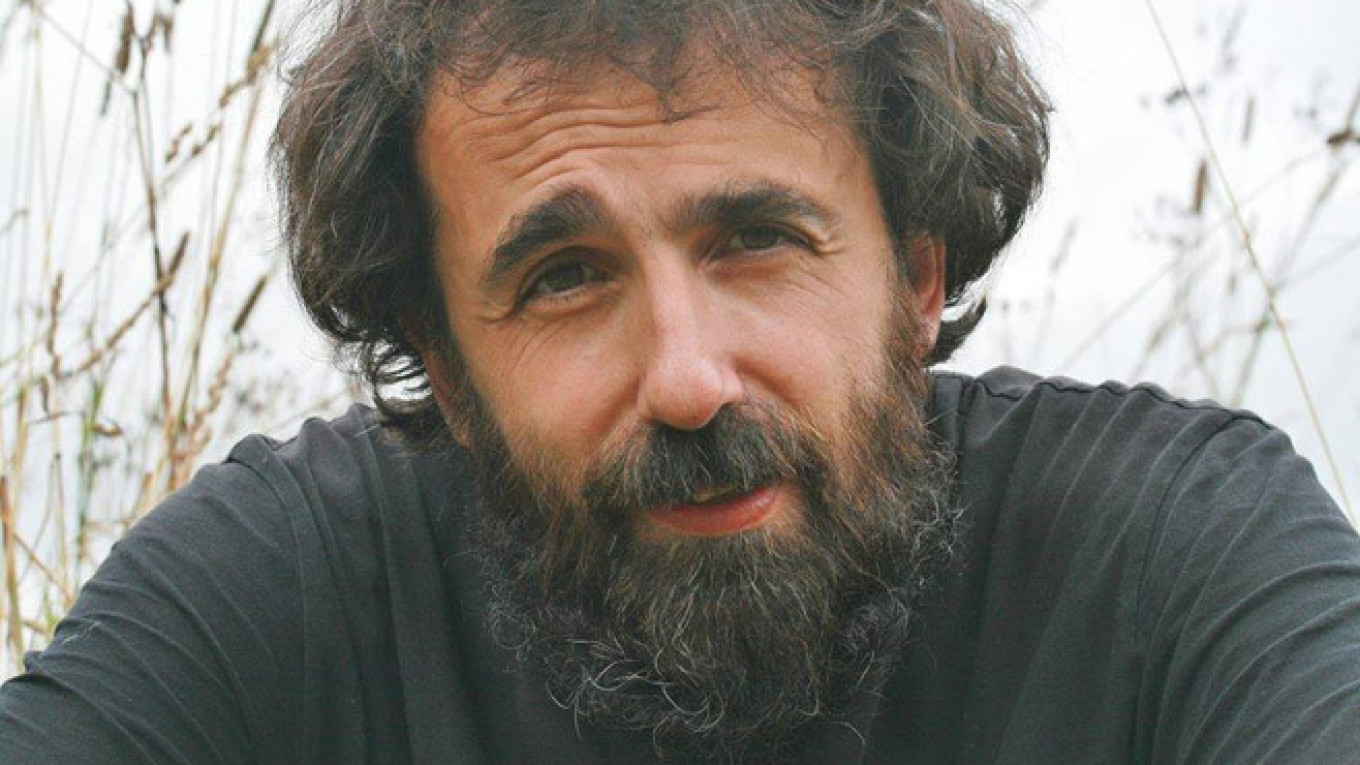

Mikhnov-Voitenko, 46, is not an entirely typical Orthodox Christian priest: The son of the late dissident singer-songwriter Alexander Galich — a darling of Soviet intelligentsia expelled from Russia in 1974 — Mikhnov-Voitenko was among the founding fathers of the uncensored Russian television in the 1990s until he quit to serve the Lord, disgruntled by failure of his ambitious TV projects.

In any case, the outspoken cleric has done what his superiors avoided: The Moscow Patriarchate has refrained from either endorsing or chastising combatants and warmongers fighting in Ukraine, where — by the UN's estimate, 2,600 lives have been lost since April — in the fight between the Ukrainian army and a pro-Russian insurgency.

While Patriarch Kirill also sees the conflict as a "fratricidal war," according to his spokesman Volkov, the hierarch's sentiments have been limited to an expression of "deep concern" over the situation.

Embracing the Kremlin

Tellingly, Kirill has retained public contacts with Ukrainian authorities, including President Petro Poroshenko, who has been vilified by pro-Kremlin state media.

This balanced approach stands in stark contrast to the position taken by the Moscow Patriarchate during the much-contested presidential elections in Russia in 2012, which saw Vladimir Putin return to the Kremlin amid unprecedented mass protests and allegations of election fraud.

Patriarch Kirill explicitly endorsed Putin's bid after trying for some time to stay out of the fray. Church hierarchs denounced opposition protests at the time.

Kirill, enthroned in 2009, has led a sweeping program to bring the church into all spheres of public life, from charity programs to schools and the army.

But the church has overreached, and is now unable to manage its social programs and massive assets — including thousands of church buildings — without state support, said Lunkin of Sreda.

The Kremlin has embraced traditionalist rhetoric since 2012 to better counterpose the liberal opposition, and was able to co-opt the church into endorsing its new policies, Lunkin said.

Exodus Looming

But the Moscow Patriarchate has to step very gingerly in Ukraine, said philosopher Goryunov.

The Ukrainian Orthodox Church is the biggest of Ukraine's Orthodox churches, and the only one recognized by other Orthodox churches worldwide.

Backing the Kremlin on Ukraine could prompt an exodus of the flock from the Moscow-controlled church to the other branches, Goryunov said. Most Ukrainians support official Kiev's stance on the rebellion, and so do independent churches.

"It's all about Ukraine," Goryunov said. "If Patriarch [Kirill] starts to act gung-ho, everyone there will desert him."

Lunkin suggested that the Kremlin may be pressuring the Moscow Patriarchate for support, but only behind closed doors and so far to no avail.

"But Patriarch Kirill may cave in yet, given how he changed his mind [on the elections] in 2012," Lunkin said.

Kirill said in Putin's presence in July that Russia "poses no military threat." It remains unclear how many followers it has cost his church.

Contact the author at a.eremenko@imedia.ru

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.