Olesya asks if her glittery hair clips are in place, if her hot pink lipstick needs reapplication.

It's all she can do to detract attention from the stump where her arm used to be, the price she paid for injecting drugs even after the site became gangrenous.

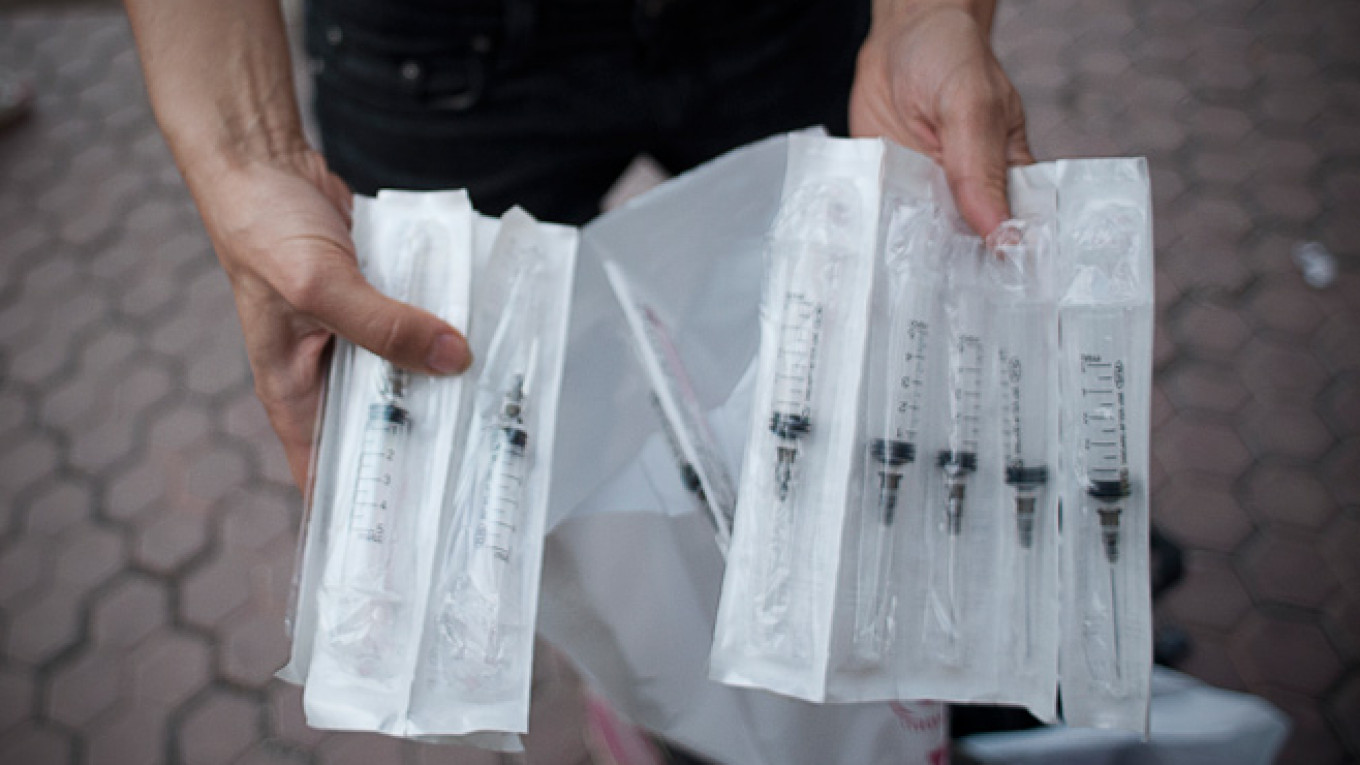

People walking past the pharmacy where volunteers chat with Olesya — an intravenous drug user with HIV — glare at the young woman, quickening their pace as they go. Others, many of them also young women, stop to accept the clean syringes, HIV tests and pregnancy tests being handed out as part of an outreach program to do the things that many specialists say authorities are not: acknowledge the fact that a full-blown HIV epidemic is becoming more and more of a reality each day.

Behind the pharmacy in northern Moscow is a field where some drug users go to shoot up. This one, in stark contrast with many others, is mostly free from used syringes.

"There is one other field that is just a carpet of used syringes," one of the volunteers says.

The same group running the outreach program, the Andrei Rylkov Foundation, a grassroots organization in Moscow that seeks to promote awareness of drug addiction and develop a humane drug policy, conducts periodic cleanup operations in public places to dispose of used syringes. These are often the same parks where families take their children to play, an alarming reminder of how close the epidemic is to spreading to non-drug users.

Olesya pulls up her pants to reveal another festering injection wound.

"Maybe you should go to the hospital," the volunteers tell her.

"Will they take me?"

"You're officially registered as a Moscow resident, right? Then they'll take you."

"Last time they refused because of my leg. They said gangrene is for drug addicts."

See No Evil

"It's obvious that we need to work with drug users; they have always been around and always will be. For more than 1,000 years there has been a culture of drug use. … Neither you nor I, nor [former public health official Gennady] Onishchenko, nor [Health Minister Veronika] Skvortsova, nor [President Vladimir] Putin have a magic cure to stop them being drug addicts. There isn't one," says Ilya Lapin, an HIV activist who works with patients on behalf of Esvero, a non-profit partnership that conducts preventative programs among members of the population especially vulnerable to HIV in more than 30 Russian cities.

Last year, there were an estimated 8.5 million drug users in the country, according to the Federal Drug Control Service. That number had skyrocketed from 2.5 million in 2010.

Activists have long warned authorities that the rise in HIV infections in recent years is a direct result of this spike in the number of drug users, but many say the problem is mostly being ignored.

"It's always the same thing: We say there is a problem, the government says there is not," Lapin said.

Pavel Aksyonov, the general director of Esvero, said the government had conducted preventative measures across the entire spectrum of the population except for the one group that is most vulnerable to HIV infection: drug users.

"Sure, it's hard to supervise their treatment, hard to catch them. They are wrongdoers and all that, but they are not martians, they are part of our society … and as long as society ignores their problems, they won't go away, they just go underground," Aksyonov told The Moscow Times.

Too Little, Too Late

Even the most zealous activists in Russia's fight against the spread of HIV agree that, compared to several years ago, there has been progress — but not enough to stave off the epidemic that they say is undoubtedly coming if the government does not take more drastic measures to confront the problem.

Last year, the country's health watchdog recorded nearly 78,000 new cases of HIV infection, compared to 69,000 in 2012 and 62,000 in 2011.

As of Jan. 1 of this year, there were 798,122 Russians registered as HIV-positive, more than 7,500 of them children.

"Even if the Russian government wakes up and finally begins to really actively fight the epidemic, the effect of preventative measures will not begin to show until two or three years later, and by that time Russia will need to cure up to 1 million HIV-positive people, which requires huge resources: not only money, but also infrastructure, doctors, etc.," said Vadim Pokrovsky, director of the Federal AIDS Center.

Andrei Skvortsov, coordinator of the grassroots organization Patients' Watchdog, which monitors the government's treatment of HIV-positive people, echoed that sentiment.

"If 18 billion rubles ($500 million) is continued to be allocated each year for the epidemic that keeps growing, rather than the 40 billion called for in the state program, a catastrophe awaits us. … Maybe the ministers will start to actually think about these things when they begin to bury their own children, and not just ours," Skvortsov said.

Aksyonov of Esvero said that the government had improved its efforts in the fight against HIV in the past several years — setting up a coordination council within the Health Ministry in February 2013 to handle HIV issues, and improving diagnostics and treatment — but the situation has nonetheless deteriorated in the past couple of years, he said.

Both he and Lapin cited the government's often hostile attitude to NGOs as a factor.

"Unfortunately, in Russia, once again this negative attitude to Western technology, to the Western understanding of the problem is making a comeback. This has a negative effect on both the epidemic and the treatment of patients," Lapin said.

"With everything we achieved with the help of NGOs in Russia, unfortunately, right now we are moving backwards. Why? Because the government does not support the programs implemented by NGOs that are recognized all over the world: harm-reduction programs, safe-sex programs."

Lapin said his group had once asked the government for funds that had been promised earlier only to be "told that we are foreign agents, that we promote pedophilia, homosexuality and drug addiction. It all comes back to that."

"That's why, unfortunately, these programs that, in my view and in the view of the international community, are effective, are retreating if not to the underground, to the shadows," Lapin said.

Activists handing out HIV tests and clean syringes.

Funding Crisis

The warnings voiced by activists and specialists come at a particularly critical time in the country's fight against the illness: Russia is now classified in the international effort as a donor country, not a recipient, meaning it contributes funds to help other countries fight the disease and as such is not afforded the same privileges from international organizations like the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria.

"The problem is that Russia helps the Global Fund but does not increase funds for the fight against HIV/AIDS within the country," Pokrovsky said.

Financing from the Global Fund, which has provided the bulk of HIV/AIDS funding to Russia for nearly a decade, is set to be drastically reduced by 2015 and phased out by 2017 in connection with Russia's new classification.

Russia's decision to become a donor country was met with cautious optimism by the international community, but activists say it is not ready.

"Russia has become a developed country in the eyes of the World Bank, and thus we can provide things for ourselves, and more than that we have even become a donor country for various international organizations, so we finance harm-reduction programs in other countries that we forbid here at home," Lapin said.

"That's why when we appeal to international organizations, they say 'Wait, you yourselves are giving us money for this.' It's a stupid situation. But the government is nevertheless closing its eyes to that as well."

Not the Russian Way

Drug substitution therapies are financed by Russia in other countries but outlawed domestically. The same is true for clean needle programs and needle disposal programs.

Clean needle programs are conducted exclusively by nongovernmental organizations like the Andrei Rylkov Foundation, as the official line on such programs is that they promote unhealthy lifestyles and do nothing to curb the rate of infection.

Maria Preobrazhenskaya, one of the activists from the Andrei Rylkov Foundation who distributes syringes, HIV and pregnancy tests and other medications to drug users each week, said police sometimes stop to scold her or other volunteers for what they see as promoting drug use.

Outside the pharmacy in northern Moscow, nearly a dozen people in two hours stopped to accept HIV tests and brochures with information on the disease from Preobrazhenskaya: a dozen people who activists say, at the very least, have more awareness than they did before.

According to Pokrovsky of the Federal AIDS Center, the programs outlawed in Russia have proven to be effective in Europe, U.S. and Canada, and they could work just as well here.

"The problem is that it has not been analyzed in depth in Russia. The bias against methadone in Russia is based entirely on the opinions of certain experts who may have their own motives for being against the drug," he said.

According to Anya Sarang, president of the Andrei Rylkov Foundation, the use of methadone in treating heroin users would solve more than just the problem of infection.

"You're hooked on heroin: Switch to methadone. Then you will not need to steal from your grandmother or wife every day. You'll get methadone for free. Of course it will no solve the problem of addiction, but it will solve a bunch of other problems: crime, health and more. But we don't even have [this practice], although in Iran, China and India — everywhere else they do this. But with us, this simple solution just evokes idiotic opposition from the government," Sarang said in comments published on the foundation's website late last month.

No Access to Medication

Worst of all for Russia's existing HIV patients, the medication they desperately need to stave off their development of their illness is not always available to them.

Up until mid-2013, the Health Ministry had run a centralized system for medicating HIV-positive people. But last year, the ministry decided to hand over responsibility for the procurement of medications to regional authorities.

As a result, patients in regions including Moscow, Nizhny Novgorod, Ivanovo, Perm, Krasnoyarsk, Novosibirsk, Kazan, Kaliningrad, Murmansk and Rostov-on-Don have complained about a lack of access to life-sustaining medications throughout much of 2014.

The website Pereboi.ru, which tracks shortages of medications for HIV-positive patients, has been inundated with warnings and complaints of deficits.

"For the third month in a row now, I am unable to get my full set of medications," wrote one patient from Murmansk in late July.

Activists say the decision to delegate medications procurement to regional authorities only muddied the waters in an already overly bureaucratic system.

"They put all responsibility on the regions. Now there is no one to make demands to," said Skvortsov of Patients' Watchdog. "The ministry says they are allocating the money to the regions, and they in turn are supposed to buy everything," but then the regional bureaucrats respond by "citing resolutions and decrees of the Health Ministry or playing ping-pong with the patients," he said.

Skvortsov said that even if officials wanted to help patients, the move created so much red tape that it made it virtually impossible.

Although the work of Skvortsov's group prompted prosecutors in Murmansk to look into these shortages and ensured early supplies of medications in some cities, he said it was a sad but undeniable truth that the patients who survive in today's Russia are those who are prepared to fight for the state medical care to which they are entitled.

Lack of Political Will

The main method for receiving funding from the Health Ministry for preventative programs — which all specialists agreed is the most crucial part of the fight — is tenders run by the ministry.

But according to Aksyonov of Esvero, there is no mechanism in place to check the effectiveness of the projects implemented by the tender winners: Funding is being funneled into programs that have not been properly vetted, and nobody bothers to check whether these programs have any result at all.

Lapin said such problems were symptomatic of an overall lack of political will to fight the epidemic. "Nothing changes [in the fight against HIV]. ... If there is no political will, we probably won't be able to change anything," he said.

"We'll try, we'll make temporary changes. But financing will run dry, programs will end. Yeah, we'll save some lives, which is very, very important, but at some point people will just get tired of running in circles," he said.

Contact the author at a.quinn@imedia.ru

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.