Foreign political analysts frequently question the rationality of President Vladimir Putin's policies, especially when they differ so markedly from those of other world leaders.

But in my view, even a cursory analysis of Putin's personal history provides a simple explanation. Putin's professional career was twice overturned by the democratic process, and consequently he sees it as his greatest threat. Furthermore, although he is not the first leader to be unduly influenced by personal history, Putin's obsession is particularly resistant to change.

In both instances, the fears of a small group decided the foreign policy of a world power.

Putin was a relatively successful young man, hired by the vaunted KGB soon after graduating from university in the mid-1970s. His 10-year career trajectory was impressive: He obtained a post in East Germany and rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel, a respected achievement in the Soviet era.

However, as democracy spread like wildfire in the 1980s, the underlying principles of the communist system began to blur and the KGB lost its former status. To stay in the game, Putin found a place for himself close to former St. Petersburg Mayor Anatoly Sobchak, without a doubt one of the officials responsible for destroying the old Soviet order.

Putin was skilled at climbing the career ladder and by 1994 the future president had secured the post of first deputy chairman of the St. Petersburg government. But in 1996 Mayor Sobchak lost the election to one of his deputies, and Putin was again out of a job. Only after some time was Putin able to gain a foothold in Moscow and begin his next, final round of promotions, culminating in his current 15-year run in the Kremlin.

All of this makes it possible to understand what Putin fears most. More than anything, he is afraid of democracy and free expression of the popular will. Twice democracy defeated him, first throwing the KGB under the bus and then taking Sobchak from power. The entire history of his presidency has thus been a process of narrowing the democratic "field" that he first inherited from former President Boris Yeltsin and, to some extent, from the president-turned-prime minister, Dmitry Medvedev.

Putin's return to the presidency in 2012 was largely due to the events of the "Arab Spring," which convinced him that Russia's stability was at risk. His foreign policy failure in Ukraine in 2004 and his feeling that a new failure was imminent in 2014 prompted him to harden his position this spring, actions that he will never admit were a mistake.

In this way, the fears of a single person, and the team he has assembled from friends over various periods of his career, have formed the policy of a leading world power.

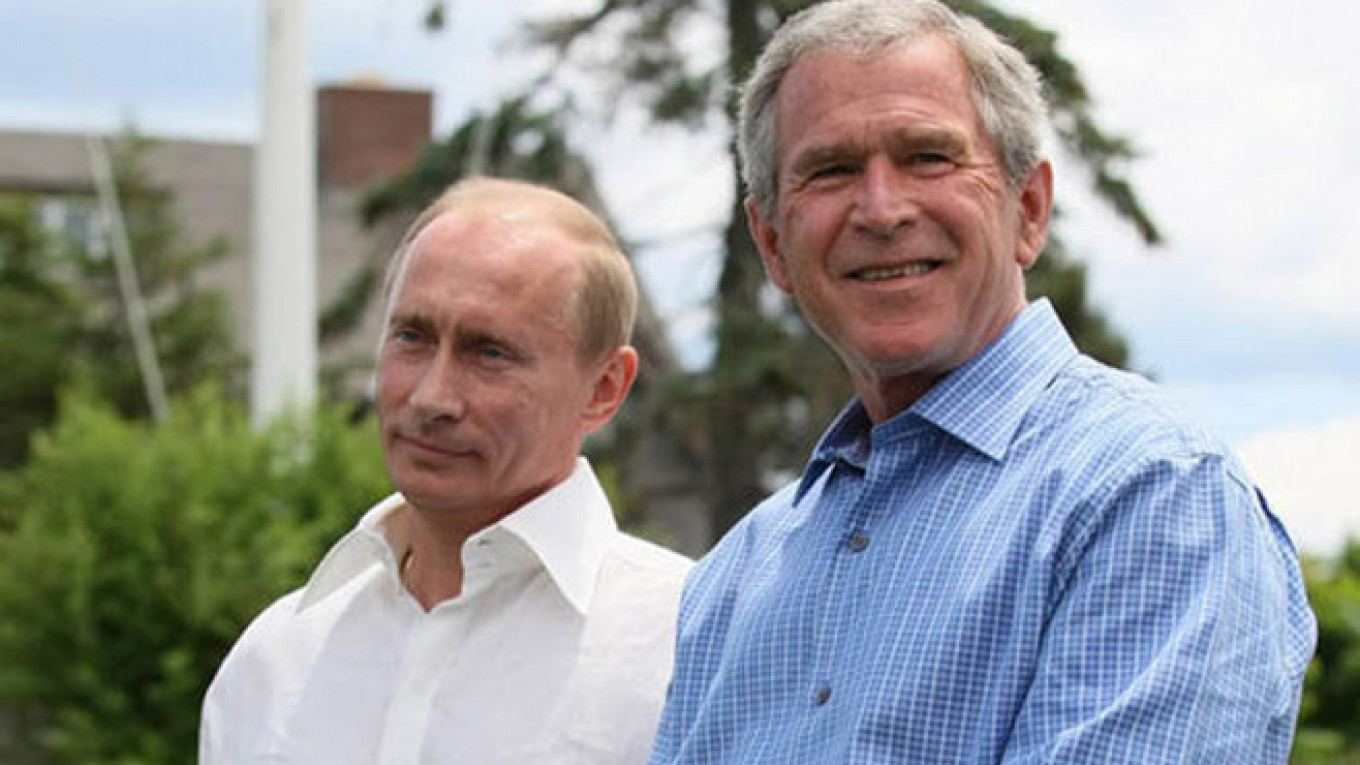

Putin, of course, is not the only world leader to have been influenced by personal fears and complexes: This was also true of former U.S. President George W. Bush and his inner circle.

Most of the members of Bush's team — former U.S. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, former U.S. Vice President Dick Cheney, former U.S. Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz and a number of others — began their political careers in the late 1960s and early 1970s, when the Vietnam War was at its height. Their support for the war, and their dismay over the U.S.'s humiliating defeat, eventually encouraged them to develop a militaristic and confrontational world view.

When they returned to big-time politics under former U.S. President George Bush Sr., they were determined to establish a new international role for the country. Although pushed out of power by the Democrats, their passion for projecting U.S. power essentially preordained the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq. A similar passion prompted Putin's current gamble in Ukraine.

The results of Washington's actions are perfectly clear: Despite the $1.2 trillion spent on the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq and the thousands of U.S. lives lost in those battles, let alone civilian casualties, the ventures were unsuccessful. Both Afghanistan and Iraq are now far more unstable and dangerous than they were prior to the U.S. invasions, and support for the fundamentalists and anti-U.S. forces in the region has only grown.

The events unfolding today in the Middle East and Ukraine are the result of reckless policies set in motion by two world leaders governed by their own personal fears and complexes. It will take many years to completely overcome the consequences of such ill-conceived political decisions.

But whereas the U.S. leadership has since made major alterations to its outlook, Putin has only become more confirmed in his "conservatism." This way of thinking requires the destabilization of neighboring countries that might otherwise take a pro-Western path, thus presenting Russians with a more attractive alternative and undermining the foundations of Putin's system.

Unfortunately, Putin's hardened outlook means it is highly unlikely that any combination of sanctions or international condemnation will stop him. He will continue pursuing his policies of curtailing democratic freedoms at home and putting pressure on any neighboring countries that seek an alternative path of development.

Putin's Russia is becoming increasingly dangerous for the world. This is all the more so because Russia, unlike other countries where leaders have made similar miscalculations, lacks a legitimate mechanism for the peaceful transfer of power away from the "national leader."

Although both the East and West have had their share of misguided rulers, Putin's particular enmity for democracy has compounded the magnitude of the problem now facing the West.

Vladislav Inozemtsev is a professor of economics, director of the Moscow-based Center for Post-Industrial Studies.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.