This article was taken from the Moscow Times archive and was first published on July 12, 1994.

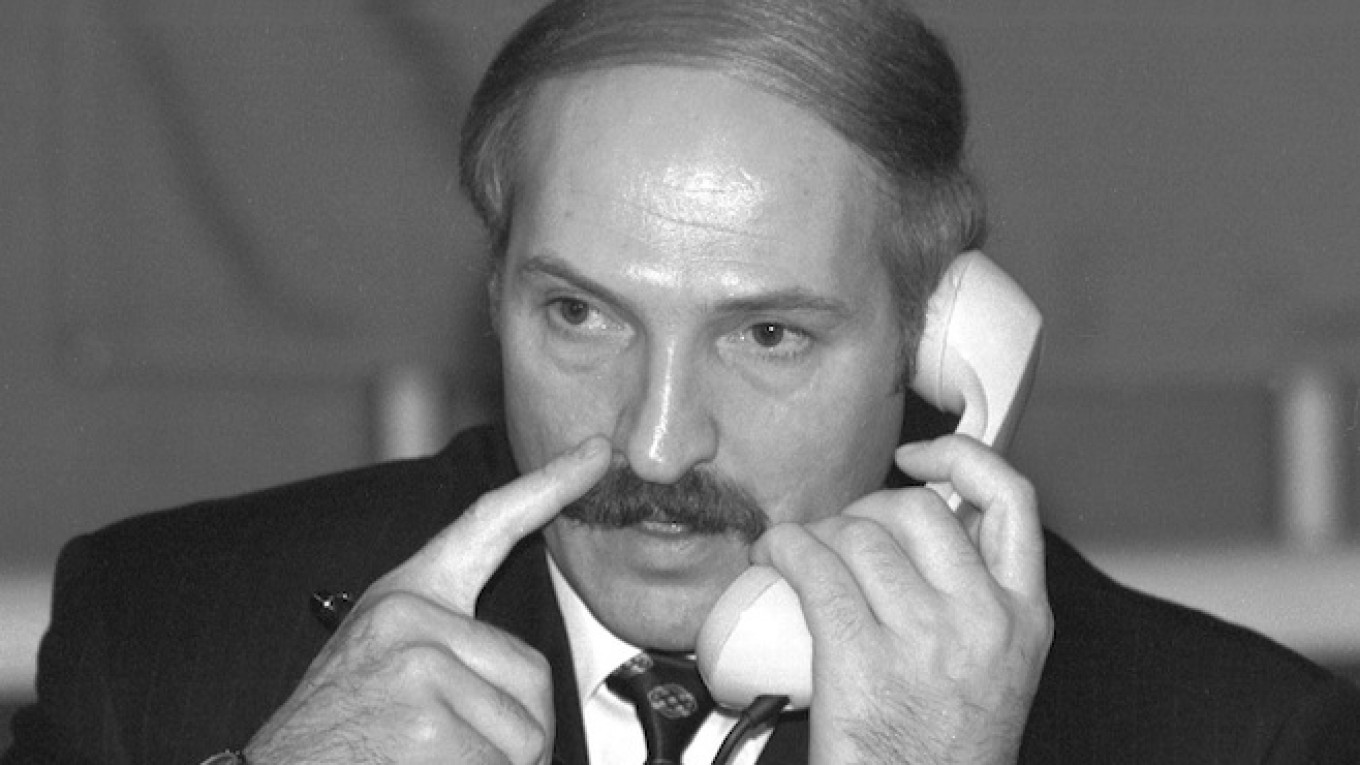

MINSK, Belarus -- Alexander Lukashenko, the flamboyant populist who has promised to clamp down on corruption and restore the Soviet Union, was set to take power Monday after winning a landslide victory to become the first elected president of Belarus.

In a lopsided run-off vote Sunday, Lukashenko, 39, won over 80.12 percent of the turnout against only 14.2 percent for the man he has vowed to put behind bars, conservative Prime Minister Vyacheslav Kebich, 59, according to preliminary results provided by the central election commission.

In Sunday's balloting, 69.9 percent of Belarus' 7.5 million voters took to the polls, responding to Lukashenko's 11th-hour appeal for a large turnout. If voter participation had been less than 50 percent, another election would have been required.

Lukashenko will take the oath of office and assume the presidency when the Belarus parliament convenes later this month. Parliament speaker Mechislav Grib said the session would probably be held July 19, Belinform news agency reported.Kebich, apparently taking the result as a vote of no confidence, resigned Monday as prime minister, a post he has held since 1990. But his deputy Mikhail Miesnikovich said the Kebich government would continue to work until Lukashenko takes office.

Speaking after he cast his vote in his home town of Shklov, 200 kilometers east of Minsk, Lukashenko said, "There will be radical changes in the government as soon as I take the oath, but honest people will stay in work," the agency reported. Lukashenko's grassroots campaign and promise to lead the country from crisis by routing corrupt officials from their posts apparently struck a chord with Belarus' voters, who are reeling from the effects of the Kebich government's economic policies: factories at a near standstill, 50 percent monthly inflation, and the woeful buying power of the local currency, called the zaichik, or "bunny," which trades 25,100 to the dollar.

"Kebich said he had provided us with the survival minimum," said Anna Tolkach, a farmer in Dzerzhinsk region, 50 kilometers west of Minsk. "Hah! 80,000 zaichiki a month! What kind of minimum is that? Lukashenko will restore order."

But many in the Belarussian capital appeared more concerned about what reprisals might be in store from Lukashenko, who is often compared to Russian ultranationalist Vladimir Zhirinovsky for his promises of resolute action against his enemies.

"Lukashenko is a dictator; we need a leader, not someone who is going to shoot people and put them in prison," said Vasily Panysh, a Minsk construction worker. "Like Zhirinovsky, he will try to start a war with everyone."

Lukashenko has heard the Zhirinovsky comparisons, and dismissed them with forecasts of civil upheavals.

"Who is going to fight against a president who has been elected by the people? Seventy corrupt bureaucrats?" Lukashenko said in a recent interview. "They've all got their suitcases packed and their tickets for somewhere in the Himalayas."

Although the former collective farm director supported the 1991 hardline coup against Mikhail Gorbachev and now calls for the immediate resurrection of the Soviet Union, he insists that he is not a Communist retread.

"I am not red," Lukashenko said. "I am not going to go back to the dogmas I got rid of long ago."

But the planks of Lukashenko's program -- halting privatization of industry, a ban on land privatization, and a return to state management of the economy -- leave little hope for Belarus' embryonic market reforms.

"The first thing Lukashenko will do is shut this all down," said Oleg Gulevich, 25, a young entrepreneur who sells cheap imported clothing and other goods from tents at Minsk's Dinamo stadium. "He doesn't realize that if I invest my money in something, it's business. He thinks it's speculation."

Despite Lukashenko's calls for closer ties with Moscow, many Russian officials believe the defeat of Kebich is a setback. Deputy Prime Minister Alexander Shokhin expressed concern about a possible Lukashenko victory, saying it would mean starting from scratch negotiations on a planned monetary union between the two republics.

A self-styled underdog who shot from obscurity to national popularity as head of an anti-corruption drive this spring, Lukashenko turned to his advantage the state-run media's barely concealed and often embarrassing efforts to discredit him.

Election officials said 90 percent of soldiers and police voted for Lukashenko and he swept rural areas.

Despite his overwhelming victory, Lukashenko's ability to deliver on his promises will depend largely on his relationship with the Soviet-era parliament, which in recent months has been a bastion of support for Kebich. And once in office, Lukashenko may turn out to be less radical than his campaign promises indicate.

Read more stories from our archive every Friday оr search the archive yourself here.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.