In the depths of the Russian State Library, Marina Chestnykh takes the creaking elevator up to the ninth floor. She walks past stack after stack of books behind metal cages, the shelves barely visible in the dim light from the frosted-glass windows. This is the spetskhran, or old special storage collection — the restricted-access cemetery for material deemed “ideologically harmful” by the Soviet state.

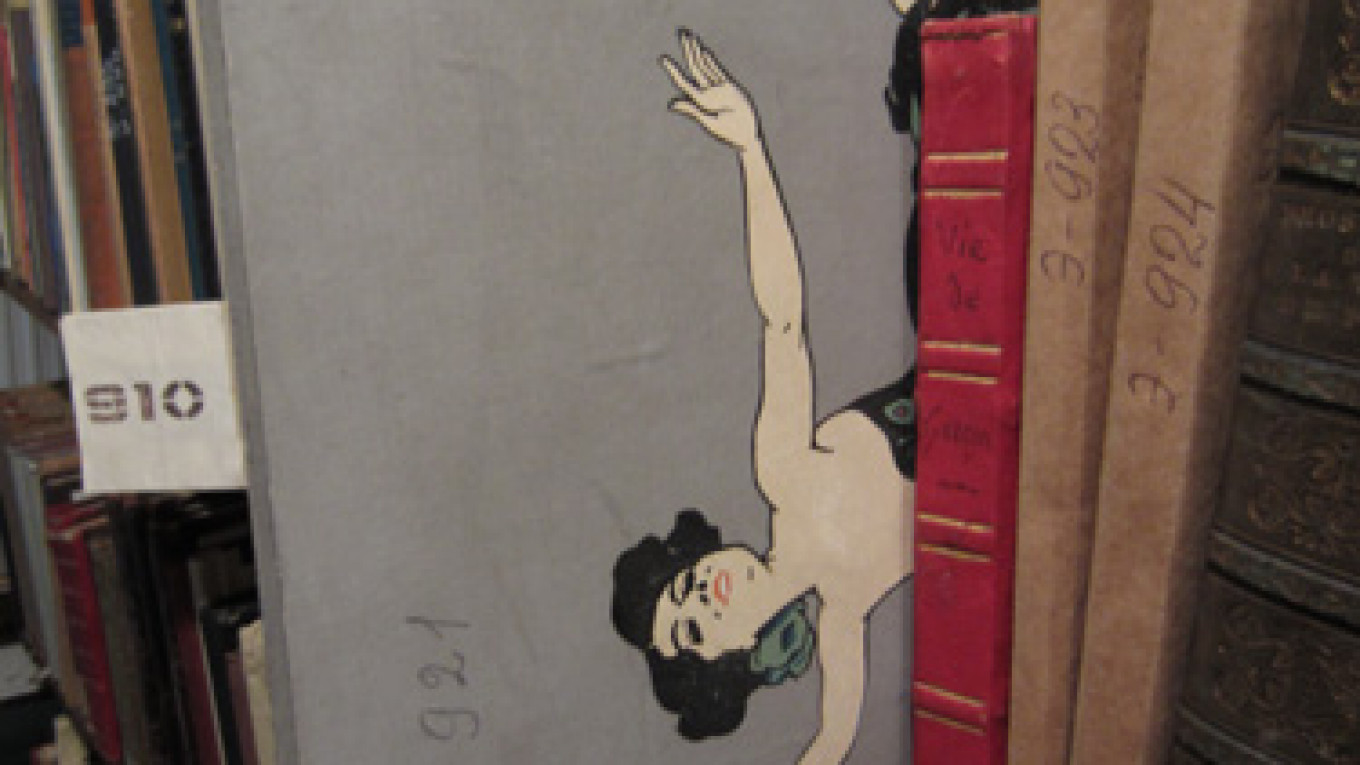

She arrives at a cage in the floor’s back corner. When she inserts a key in the padlock, the door swings open to reveal thousands of books, paintings, engravings, photographs and films — all, in one way or another, connected to sex.

It was the kinkiest secret in the Soviet Union: Across from the Kremlin, the country’s main library held a pornographic treasure trove. Founded by the Bolsheviks as a repository for aristocrats’ erotica, the collection eventually grew to house 12,000 items from around the world, ranging from 18th-century Japanese engravings to Nixon-era romance novels.

Off limits to the general public, the collection was always open to top party brass, some of whom are said to have enjoyed visiting. Today, the spetskhran is no more, but the collection is still something of a secret: There is no complete compendium of its contents, and many of them are still unlisted in the catalogue.

“We chose to preserve it intact, as a relic of the era when it was created,” Chestnykh said.

Chestnykh, who traverses the drafty stacks in a purple knit poncho, is the collection’s main overseer. After joining the library in the 1980s, she only learned of its existence in the 1990s, when she was asked to help reassign its holdings to a different department.

Did its contents come as a surprise?

“Yes and no,” she said. “There was a special collection, so I knew something pretty special had to be kept there.”

The collection’s story begins in the 1920s, when the Bolsheviks turned what was once the Rumyantsev arts museum into the country’s national library. As the newly anointed Lenin Library began amassing new literature, it also opened a rare book department to house compromising materials, acquired primarily from confiscated noble libraries.

One of the most stunning items seized from an unknown owner is “The Seven Deadly Sins,” an oversized book of engravings self-published in 1918 by Vasily Masyutin, who also illustrated classics by Pushkin and Chekhov. Among its depictions of gluttony is a large woman masturbating with a ghoulish smile.

Before the revolution, it was fashionable among the upper classes to assemble so-called knigi dlya dam, or “Ladies’ Books,” a kind of bawdy scrapbook. Anostentatious leather-bound album with “Kniga Dlya Dam” embossed in gold on the cover opens to reveal a Chinese silk drawing of an entwined couple. Farther on, dozens of engravings show aristocratic duos fornicating in sumptuously upholstered settings.

For the full gallery see: Inside The Soviet Secret Erotica Collection

Erotica was also consumed by Russia’s masses, as evidenced by a set of pamphlets from the 1910s. A pamphlet labeled “Pikantnaya Biblioteka,” or “Naughty Library” containing a tale from the 14th century Italian classic “Decameron” and a story titled “A Consultation,” retailed for 50 kopeks. On the cover, a satanic figure grips a silky-tressed damsel in distress.

In the 1930s, increasing control over books led to hundreds of new additions. Items deemed inappropriate now extended to Soviet writings on sexuality from the previous decade, when abortion was legalized and Alexandra Kollontai, the most famous woman in the Bolshevik government, called for the destruction of the traditional family — a movement reversed under Stalin.

One 1927 publication provided a round up of scientific research into birth control methods. Another title from the same year looked at “Delinquency in the Sphere of Sexual Relations,” with charts on subjects such as “The Social Composition of Sex Criminals.”

The collection got its biggest boost from Nikolai Skorodumov, who began collecting books while at school, and eventually became the deputy director of the Moscow State University library. The librarian led a quiet personal life, taking on his maid as a common-law wife, but his appetite for books was voracious. Interested in rare Russian material as well as foreign acquisitions from France, Germany, the U.S. and beyond, Skorodumov kept collecting until his death in 1947.

Among Skorodumov’s treasures was a portfolio of drawings and watercolors by the avant-garde titan Mikhail Larionov. Made in the 1910s, they are no less scandalous in today’s Russia. One pencil sketch features a happily panting dog standing in front of a human, who is engaged in much more than petting. A watercolor depicts two soldiers having an intimate encounter on a bench.

How did Skorodumov amass such a collection when owning a foreign title could result in a Gulag sentence?

There are 12,000 items in the collection, from Japanese engravings to 1970s romance novels.

First, he was careful to frame it within the discourse of communist ideology, receiving documents from a variety of organizations attesting to its scientific value. Ivan Yermakov, the director of the soon-to-be-disbanded State Psychoanalytic Institute, provided one such letter in 1926:

“Sexuality demands serious and rigorous scientific examination, particularly as it has played such an extensive role in the evolution of culture and daily life,” wrote Yermakov, who published many of Freud’s works in Russian for the first time. “It is highly important to preserve the collection in unadulterated form as a socially valuable work.”

There is also a second theory. Stalin’s secret police chief Genrikh Yagoda — a pornography aficionado whose apartment reportedly held a dildo collection — is said to have enjoyed viewing Skorodumov’s holdings. Librarians believe that he personally ensured the latter’s safety.

After Skorodumov’s death, the NKVD, the forerunner of the KGB, raided his collection. According to a letter sent by library director Vasily Olishev to the Council of Ministers, a post-mortem search of his apartment revealed a staggering 40,000 items, 1,763 of which were “books of an erotic nature” while 5,000 were “pornographic or vulgar” brochures and magazines.

The Soviet state snapped up the collection from Skorodumov’s widow for 14,000 rubles, then a considerable sum. However, Olishev was careful to note that the money did not extend to the erotica.

“The library did not deem it appropriate to pay citizen Burovaya [Skorodumov widow] for the erotic literature, broadsheets and magazines, as this literature presents neither scientific nor historical value to the library’s readers, and is an especially harmful vestige of bourgeois ideology,” he wrote.

For just this reason, however, it was necessary to hang on to it: “The Lenin Library did not deem it appropriate to return literature of such a harmful nature to citizen Burovaya, as its possession in the home of a private citizen presents considerable danger.”

Safely ensconced in the spetskhran, the erotica collection became available for viewing by top Stalinist henchmen. According to legend, they included the mustachioed cavalry officer and civil war hero Semyon Budyonny and grandfatherly Mikhail Kalinin, the longtime figurehead of the Soviet state.

“They were supposedly interested in the visual stuff — postcards, photos,” Chestnykh said. A Politburo member did not need a pass: “No one could refuse them.”

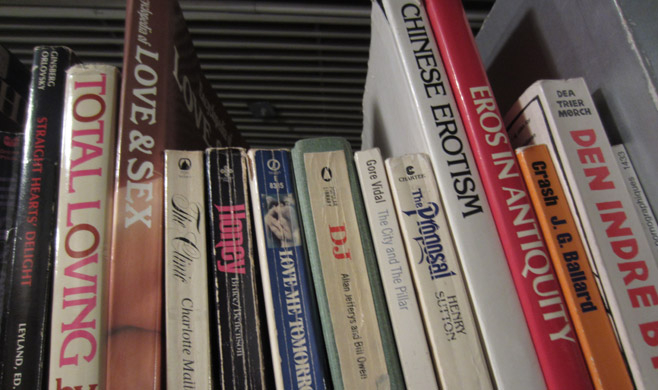

The collection’s most recent additions date from the 1960s to the 1980s, when racy-looking materials — often in English — were confiscated at customs.

“There was no system to it,” Chestnykh said. “They just took whatever seemed inappropriate.”

They bear a variety of purple stamps from the state censor, the meaning of whose numbers — 170, 230 — is puzzling even for librarians.

What resulted is a truly random assemblage: an album of Beatles photographs, an anti-homosexuality screed called “Gay is Not Good,” multiple English-language Kama Sutras, popular 1970s memoir “The Happy Hooker,” a set of bawdy limericks, a coffee table book of Picasso paintings and Gore Vidal’s “The City and the Pillar.”

Years after its existence was revealed, the collection is still awaiting comprehensive study. While some books are now available for viewing in the reading rooms — the Marquis de Sade’s writings, Chestnykh said, are the most popular among them — rarer and more delicate artifacts, such as the Larionov drawings, linger in obscurity on the shelves.

The problem is not just a lack of resources, Chestnykh said. “The management have differing opinions. Some think this material is worthy of examination and display, and others do not.”

Since the collection has never been truly open to visitors, most items remain incredibly well-preserved, “like fine wine,” Chestnykh said. However, she suspects a few things may have vanished over the years — ferried away by unscrupulous librarians, or even heads of state.

“Innocent before proven guilty,” she said with a smile, locking the metal cage’s door behind her.

Contact the author at artsreporter@imedia.ru

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.