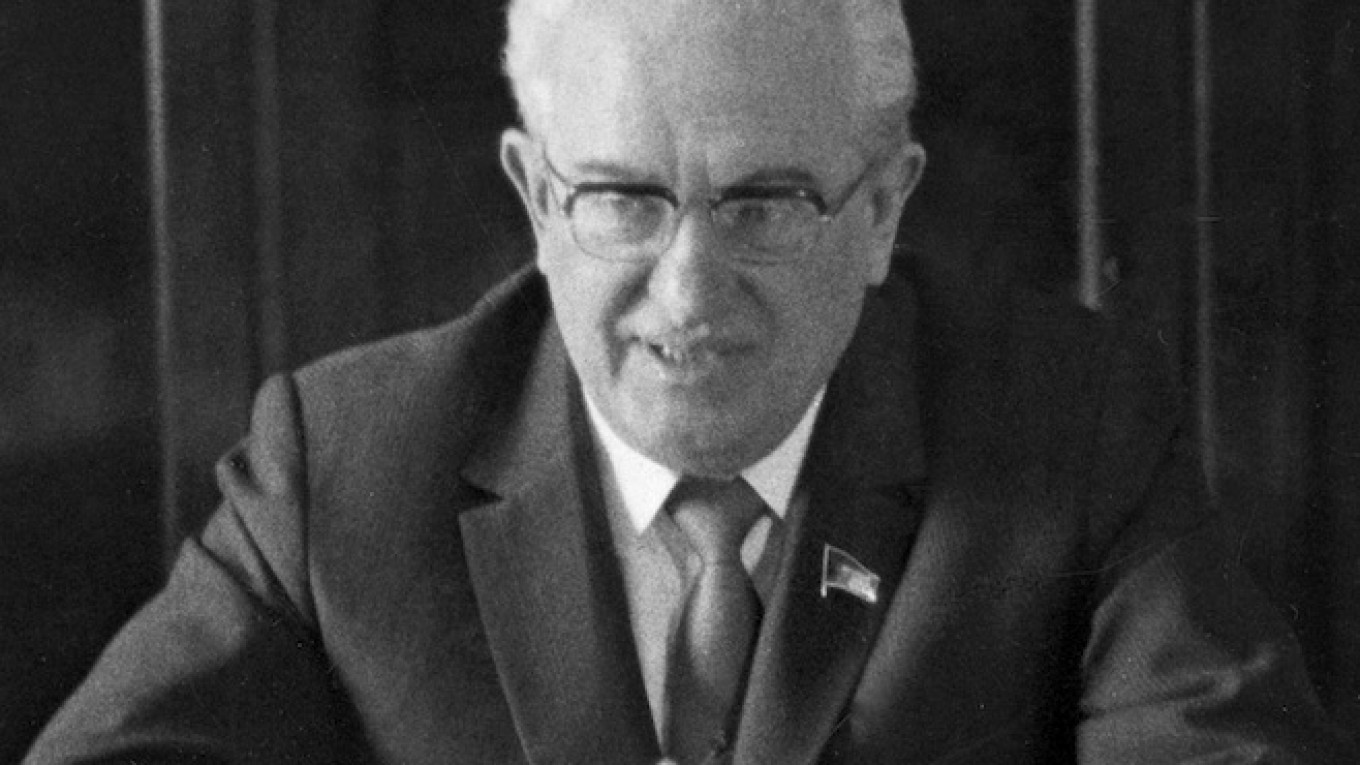

This Sunday marked the 100th anniversary of the birth of Soviet leader Yury Andropov — KGB chief, scourge of dissidents, would-be reformer and the man who, if he lived, could have perhaps spared Russia from the necessity of Vladimir Putin and his policies.

Andropov is remembered as the man who attempted a controlled upgrade of the Soviet Union while preserving it as an empire, but who died before seeing his policies come into fruition. After him, the Soviet state disintegrated all too abruptly, leaving the public wondering whether Andropov's alternative was a viable, and perhaps a less painful development route. The nagging feeling of a missed opportunity has stayed with the Russian public throughout the 25 years of capitalism — until Putin, a man of similar background and policies, ended up de-facto rolling the country back to Andropov's development model, despite its current economic unfeasibility.

A low-level party functionary with an unexciting early biography, Andropov shot to bureaucratic heights after the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, when as Moscow's envoy, he was the prime lobbyist for the Soviet invasion that drowned the rebellion in blood. This earned him a post at the Communist Party's central office — and in 11 years, the top job at the KGB, where he spearheaded the crusade against dissidents, including writer Alexander Solzhenitsyn and rights champion Andrei Sakharov. He also endorsed the Soviet invasions of Czechoslovakia in 1968 and Afghanistan in 1979.

Andropov succeeded Leonid Brezhnev upon his demise in 1982 — and delivered the tightening of the screws expected from a man of his track record. His main achievement in popular memory was sweeping daytime raids in stores and cinemas intended to boost labor discipline through cracking down on work-dodging truants. He also ordered a show case against corruption and began a purge, albeit mild, of the party apparat.

All of this was a reaction to the Soviet Union's flagging economy — but the remarkable thing was that he did not stop at repressions. Andropov promoted reform-minded economic experts who later came to prominence during Perestroika, and began experiments to introduce elements of market economics in the country.

Then he died at 69 of renal failure, 15 months into his reign. The next year Mikhail Gorbachev took his job and ushered in Perestroika. The rest, as they say, is history.

Fast forward to the 2000s to find Putin, another KGB man, in office and frequently compared to Andropov — who, by then, had become a lost dream for Russian statists. His combination of hardline political ideology and economic reformation drive instilled the belief that he could revamp the Soviet Union while preserving it as an empire — a take on the "Chinese way" along the lines of Den Xiaoping.

There are indeed many analogies between the policies of Andropov and Putin, who, throughout his time in power, has maintained the image of enlightened imperialist, at once at peace with Russia's current capitalist direction, fond of the word "modernization" (though less now than he was in the late 2000s) and at the same time increasingly conservative and mindful of ideology: He publicly rued the downfall of the Soviet Union, touted traditional values — and, yes, clamped down on dissent. So perhaps he is the one to finish what Andropov started, supporters say.

Putin is no carbon copy of Andropov. For one, Russia's incumbent never rose that high in the KGB ranks; for another, he lacks ideological drive, being a political survivalist first and an imperialist second. Compare him to Andropov, a man of unwavering ideological convictions — and note that the lack of ideological drive is a serious impediment to any sort of strategic reform.

But at the end of the day Putin is, indeed, following through on Andropov's interrupted policies of upgrading the Soviet Union without changing its core. The current state of the Russian economy is the best answer to how this is all working out — growth is grinding to a halt, and even Putin admitted it is down to domestic policies, not global trends. Perhaps "controlled change" worked out in China, and perhaps it could still work out in the Soviet Union in 1984; it is not working anymore in Russia in 2014.

However, Putin's channeling of Andropov is an answer to the public demands. The Soviets' demise was too abrupt and left too many Russians with the feeling of unfinished business. The "what if" question lingered in the public subconsciousness until Putin finally began probing back to 1984 in order to implement controlled change from there, negating the shock plunge into capitalism under Andropov's successors.

This instinctive drift toward the "Andropov way" is not about economic rationality, but about public beliefs — some things need to be tried to be believed. The test could have been gotten out of the way three decades earlier if Andropov's kidneys have held out for five more years. As it stands, Russia still has to catch up on alternative development scenarios, purging the residue of Soviet thinking from its system before it can move on to building a modern capitalist economy. All there remains is the hope that the lesson would be learned before the country gets down to slamming the Iron Curtain on Google and IMDb, introducing party oversight of hi-tech startups and offering "Game of Commissars" instead of modern TV show fare — though Russia is getting there fast.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.