The name Vladimir Izenberg does not say a lot in and of itself. It's not one that calls up images or eras, great schools or great events.

Izenberg was an artist. He was born in Petersburg in 1895 and he died in Leningrad in 1969. There is no entry about him in Russian Wikipedia and he is not listed in John Milner's prodigious "Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Artists, 1420-1970," a spectacular volume that in a flush of inexplicable generosity was given to me years ago by The Moscow Times editor-in-chief Marc Champion, and for which I remain eternally grateful. Many an obscure question has been answered for me by this book, but not those I have about Vladimir Izenberg.

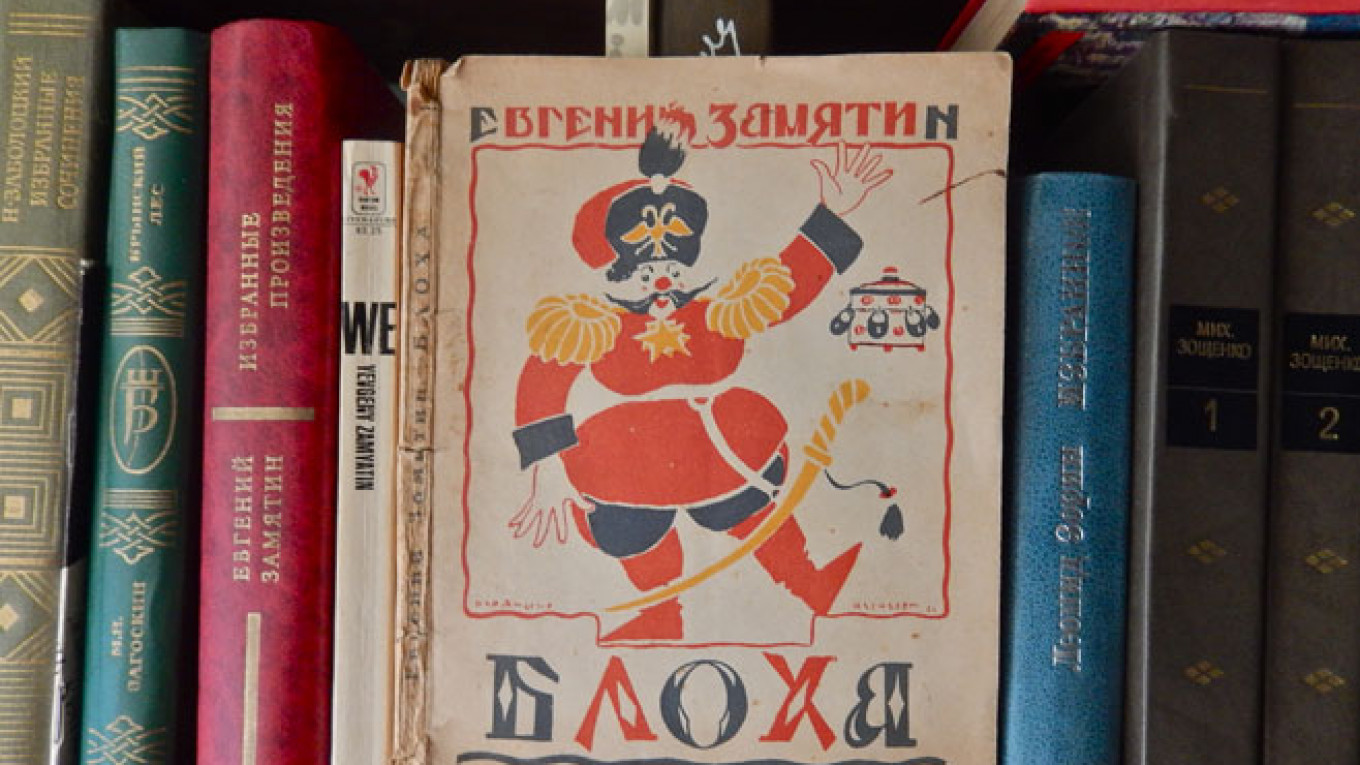

One may say that I own an Izenberg work. It's not an original, but it is an item of some rarity and beauty that justifies my distinct pleasure in possessing it. It is a 1926 edition of Yevgeny Zamyatin's play "The Flea," published by Mysl (or Thought) publishers in Leningrad. The lively cover illustration, a collage-type piece executed in three colors, was done by Izenberg and is dated 1925.

"The Flea" was based in part on Russian folklore and on Nikolai Leskov's famous 19th century short-story "Lefty." It tells the tale of an ingenious Russian craftsman who fashioned a microscopic mechanical flea after his English counterparts failed in this task of great national importance and pride.

The play was a success in 1925 at the so-called Second Moscow Art Theater. It closed in 1929 and was effectively buried in the huge pile of banned and semi-banned plays from the first decade of the Soviet Union. This is of some importance to Izenberg's illustration, for the book with his drawing on the cover was the last stand-alone publication of the play. "The Flea" was included in a four-volume collected works edition printed in 1929, and then not published again until 1989

Izenberg apparently saw the notion of national pride as a key element of the play, for his illustration shows a happy, healthy tsarist Russian general doing something of a folk dance as his sabre balances miraculously in the air. Of course, if we think more about this image it is clear that it was completely out of step with the times. Even a year later, when the nation celebrated the 10th anniversary of the revolution, it would have been an impossible topic for a book cover. Not only would the smile on the general's face be gone, the general would have been gone himself, surely replaced by the miraculous Russian peasant.

The little that we know about Izenberg could probably be contained in the same box holding Zamyatin's tiny mechanical flea. He was the son of Konstantin Izenberg (1859-1911), who was also a sculptor and a book and magazine illustrator. The son had no formal training as an artist, but curiously, he began contributing illustrations to Petersburg magazines simultaneously to his father's death. One can't help but wonder if the younger Izenberg had studied at the feet of his father and simply took over his father's commissions when the elder died.

The final sentence in a seven-sentence entry on Vladimir Izenberg in Eduard Konovalov's "Dictionary of Russian Artists" is a loaded phrase. It claims: "Worked as a theater designer in Odessa, Sevastopol and Kuibyshev."

In fact, writers and artists, sensing danger nearing in the late 1920s, occasionally struck out for locations far from the Soviet Union's major cities. It was a good way to remove yourself from the historical record, but it was also a method for staying alive. Could this be the reason for Izenberg's travels southward? In any case a Russian poster website informs us that Izenberg lived in Kuibyshev throughout the 1930s, was in Murom during the war years of 1941 to 1945, and resided in Ryazan from 1945 to 1953. He made his way back to his hometown, now called Leningrad, in 1954, one year after Joseph Stalin's death, when he was entrusted with the job of renovating his father's famous monument in Alexandrovsky Park to the minesweeper Steregushchy, which sank during the Russo-Japanese War in 1904.

Here are a few bits and pieces of other information about Izenberg's work.

In 1926 he designed the beautiful and bold cover, as well as the delightful interior illustrations, for Osip Mandelshtam's children's poem "Kitchen." All ten pages of the book are posted in vivid color on the site of Rarus Gallery. He created the collage gracing the cover of a book publication of Vladimir Mayakovsky's narrative poem "War and Peace" in 1924, and the cover and numerous illustrations inside Leonid Panteleyev's children's book "Letter to the President and Other Stories" in 1933. These collage-illustrations, four of which can be seen in a live journal entry about children's books from the early Soviet period, are unusual for they combine photographic images with simple geometric drawings.

Izenberg designed numerous political posters in the 1920s, especially in honor of the seventh anniversary of the revolution in 1924, and his designs for bookplates were in great demand. An 18-page brochure picturing ten of Izenberg's bookplates — very much in the Aubrey Beardsley, art nouveau style — was published in 1923. Four of the ten bookplates may be seen on a website called tvoyapechat.ru that provides information about Russian bookplates and heraldry. Vladimir Lenin, incidentally, owned a copy of this brochure, although chances are that his copy was one merely sent automatically to the Kremlin by the publisher.

The artist worked for various theaters throughout the Soviet years, although virtually no details of this aspect of his labor are currently available. Izenberg collaborated with the Mossadrom Theater in Odessa and the Sevastopol City Theater in the 1920s, and created designs for the Kuibyshev Drama Theater in the 1930s. In the 1960s he worked with the Leningrad Puppet Theater.

Contact the author at jfreedman@imedia.ru

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.