Former Chinese military attache to Russia General Van Yunhai recently remarked that the Ukrainian crisis had given Beijing at least a ten-year "strategic respite" from its global confrontation with the U.S. However, that prediction will probably prove inaccurate with regard to military matters. Despite Russia's military success in Crimea, it is very unlikely that anyone in Washington or Moscow harbors any illusions about Russia's strategic capabilities or ambitions regarding Europe. That is why the West is not genuinely concerned about the supposed Russian threat to Latvia and why the U.S. — as the only country that contributes more to NATO's collective security than it receives — will not invest its limited military resources in an attempt to pressure and contain Russia through force.

China is gradually but irreversibly acquiring a guaranteed and reliable trade partner in the north — essentially, its "very own Canada." Those deepening ties lie beyond the reach of Western sanctions, blockades or potential military pressure directed against Russia. In fact, it is popular among Chinese experts on Russia to point to the Canada-U.S. relationship as the optimal model for relations between the two countries.

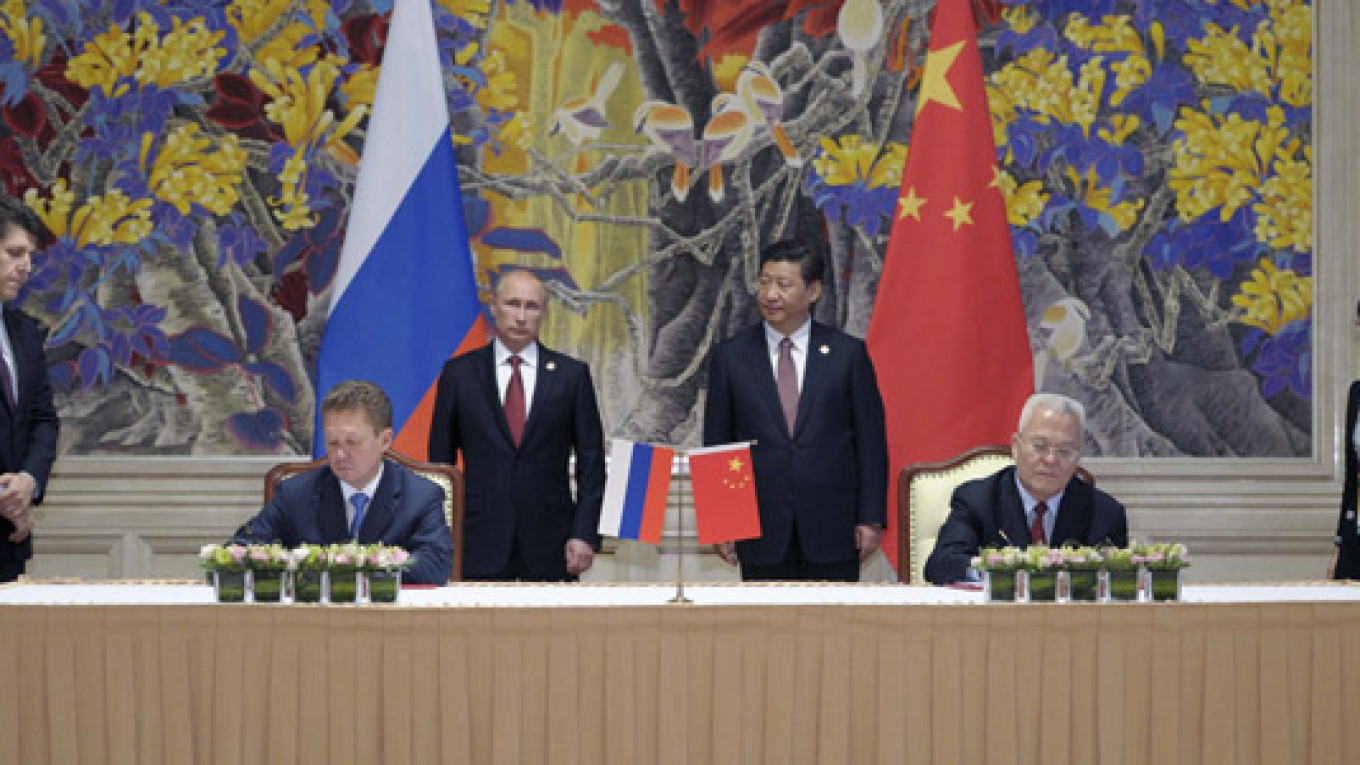

Washington is pursuing its policy of isolating Russia with the utmost determination, and, as we see, that approach is already bearing fruit. President Vladimir Putin's recent visit to China offered clear proof of just how ineffective the attempt by the administration of U.S. President Barack Obama to punish Russia has been. With the direct involvement of senior Russian and Chinese leaders, Gazprom and the China National Petroleum Corporation signed a 30-year gas contract — an unusual step in their bilateral trade and economic relations. Before this, the two countries had stressed the importance of keeping politics and business separate, and every attempt to time the signing of trade deals with visits by senior officials had failed when business conditions were unfavorable. That was true not only of the decades-long negotiations leading up to the current gas deal, but also the first contract by which Russia supplied oil to China through its eastern Siberia to Pacific Ocean pipeline.

However, the current massive gas contract was not the only important feature of the recent visit. In a joint statement, Putin and Chinese President Xi Jinping speak not only of a "new stage in relations, comprehensive partnership and strategic cooperation." They also point to the need to "resist interference in the internal affairs of other states, to reject the language of unilateral sanctions and organizations … and activities aimed at altering the constitutional order of another state or its involvement in a multilateral association or union." That statement essentially formalized the Russian-Chinese "anti-revolutionary alliance" that had begun de facto with the two countries' effective efforts to stymie Western intervention in Syria.

The range of economic agreements they signed indicates that Russia is gradually lifting restrictions on the export of sensitive dual-use technologies to China and permitting Chinese state-owned corporations to increase investment in the Russian economy. After years of fruitless negotiations, Rosatom and the Chinese Atomic Energy Agency signed a memorandum on the construction of floating nuclear power stations and, reversing its previous aversion to a Chinese presence in the Russia automobile industry, Moscow will allow China's automaker Great Wall to invest in a project in the Tula region. Leaders also signed agreements for cooperation in such high technology spheres as space and civil aviation.

They also signed raw materials contracts for pipeline and liquefied natural gas, the latter deal to be handled by Russia's Novatek. China expressed a desire to invest in the mining of coal and minerals, the manufacture of construction materials and in infrastructure development. Chinese participation in the Russian economy is becoming more diversified and varied. Most of the agreements include the involvement of large and politically influential state-owned Chinese companies in the Russian economy, thereby strengthening bilateral bonds and mutual dependence.

Putin originally planned to visit China in May to participate in the Conference on Interaction and Confidence-Building Measures in Asia, a regional security structure summit. The focus and scope of the visit changed dramatically in the few short months following the highpoint of the Ukrainian crisis, the result of which prompted Moscow to overcome years of political resistance and embark on a new series of agreements with its largest neighbor to the south.

Putin is scheduled to make an even more "significant" visit to China in November, and both sides will probably try to prepare an even greater range of agreements for leaders to sign — especially because Moscow's confrontation with the West over Ukraine is likely to grow worse by then and the damage caused by the possibility of full-scale economic sanctions against Russia could far exceed the modest 2 percent to 3 percent loss to the economy that Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev estimates. [RAB] In addition, Russian and Chinese officials usually meet every October or November to discuss military and technical cooperation, and this year's talks could prove especially fruitful.

Almost all of the agreements Putin signed during his recent visit to Beijing would have eventually been concluded anyway. Normally, they would have been part of a long process in which Moscow weighs each new agreement with China against successes in developing relations with other Asian powers such as Japan and South Korea. However, the Ukrainian crisis has compelled Russia to shift into high gear and accelerate its rapprochement with China. That approach will make it possible to solve such major challenges to the Russian economy as the need to diversify markets, develop infrastructure and increase non-energy exports. The reorientation toward China will also help minimize Russia's losses caused by Western sanctions. At the same time, the new policy might significantly limit Russia's options for political maneuvering over the long term.

Vasily Kashin is an analyst with CAST, a Moscow-based think tank. This comment appeared in Vedomosti.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.