As Russian troops remain near the Ukrainian border despite numerous promises to leave and separatists threaten to partition the country, many commentators have spoken of a Russian desire to resurrect the "Soviet Empire" and have pointed to the Russian-dominated regions of Central Asia as the next likely target for Russian irredentism.

Alexey Malashenko's latest book "The Fight for Influence: Russia in Central Asia" shows the of these fears, revealing a far more nuanced picture of the entire Central Asia region than the stereotypical "authoritarian" and "post-Soviet" labels that are commonly applied to them.

The label "Central Asia" itself is somewhat controversial: Often expanded to include the Caucasus, Afghanistan, western China and even Mongolia, most specialists today have confined the term for use specifically in reference to the five post-Soviet states of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan. During the Russian Empire and subsequently the Soviet Union, these territories saw little interest from foreigners, firmly located as they were within Russia's sphere of influence.

However, each of these countries presents unique economic opportunities: Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan possess large oil and gas reserves, while Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan hold mineral wealth and precious water resources, and Uzbekistan has a valuable cotton industry and important human capital in its large population. Each of these states faces a different set of problems and has a different set of tools available, and the way their governments have developed in the 2 1/2 decades since the Soviet Union are largely a response to these factors.

While Malashenko's book would seem to look at Central Asia solely in reference to its relation to Russia, the text is in fact broader than the title would suggest: After starting with a survey of the various international organizations present in the region, Malashenko focuses on each state individually in turn, discussing the intricacies of their government structures, economies, and ties with extra-regional powers like Russia, U.S. and China.

The picture that emerges is one of striking compartmentalization. While frequently lumped together as a region, the Central Asian states have little in common apart from their shared history and their geographic proximity — their goals and desires differ widely and are often opposed. This opposition, perhaps explains Russia's failure to resurrect a close union of the states in organizations like the CES, EurAsEc and CSTO.

While the Community of Independent States, or CIS, encompassing almost all of the post-Soviet republics, initially seemed to have the potential to become a powerful alliance, it quickly became apparent that size of the organization inhibited negotiating any kind of closer union. This in turn led to the creation of the Eurasian Economic Community, or EurAsEc, followed by the Common Economic Space, or CES, organizations that became drastically smaller as they tightened bonds between the member states. The result, Malashenko writes, is that the future of the CIS is undercut by these new alliances, while the small number of states in the new alliances means they have little practical benefit for their members.

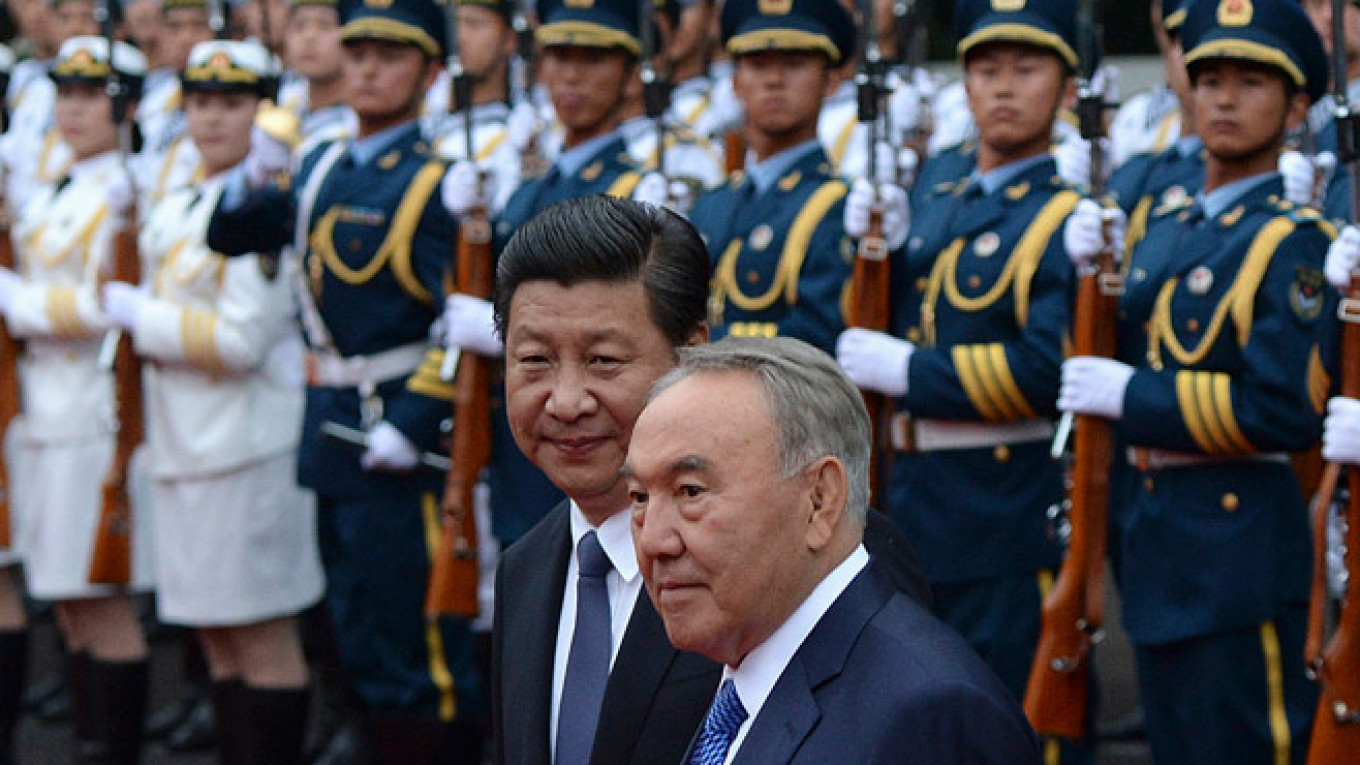

President Putin and other CSTO leaders meet in the Kremlin on May 8.

The Collective Security Treaty Organization, or CSTO, Russia's attempt to create political and military community in the post-Soviet space, has only been marginally more effective than its economic communities. Malashenko outlines the creation of a collective CSTO reaction force and, more importantly, agreements to restrict non-member states from having bases in CSTO member nations and to intervene in the internal politics of member states in times of turmoil. These last two agreements give Russia important openings to restrict foreign powers like the U.S. from gaining a military foothold in Central Asia, and also allows them a mechanism to prop up unpopular pro-Russian regimes.

However, though the CSTO might seem to give Russia a chance to dominate Central Asia, Malashenko describes the reality of the situation as somewhat different — member states use the CSTO to buy discounted Russian weapons and prop up authoritarian regimes, yet are capable of simple leaving the organization when it no longer seems to benefit them, as Uzbekistan has done.

Even more than the weakness of its international alliances, a closer look at the internal politics and cultures of the five Central Asian states reveals why Russia would have great difficulty in trying to create a closer union or create Russian-speaking separatist zones. First, the number of Russian speakers in Central Asia has drastically declined since the fall of the Soviet Union — while ethnic Russians were previously widespread throughout the area, a large proportion of these individuals have returned to Russia in the past two decades. Furthermore, as native languages have replaced Russian as the official language of government and media, local knowledge of Russian has declined to the point that post-Soviet generations are frequently unable to speak the language.

Another tidal shift that has occurred in the brief post-Soviet era is the rapid resurgence of Islam. As Malashenko describes, all of the Central Asia states have seen a return to Islam, even though some regimes have sought to crack down on conservative Islam, fearing a challenge to their regimes from Islamist parties. Despite this, most Central Asian politicians have begun to use Islam and references to religion as a way to gain support with the population. This Islamization of society would make it extremely difficult for Russia to control any portion of Central Asia, despite the relative moderation of Islam in the Central Asian states today.

Thus, Malashenko's analysis would seem to suggest that the prospect of Russian irredentist power grabs is Central Asia is very slim indeed. The region that would seem most ripe for Russian interference is Northern Kazakhstan, which shares a border with Russia and has many Russian speakers, yet Kazakhstan is the most stable of the Central Asian states and has close ties with China, as well as being Russia's partner in the Eurasian Economic Union, making it unlikely that Russia would seek to intervene in Kazakhstan.

Rather than describing growing Russian influence in Central Asia, Malashenko's book in fact makes it seem that China is the power with the most to gain in the region: The Shanghai Cooperation Organization's development bank and extensive resources offer a powerful pull to cash-strapped nations like Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan, which Malashenko at various points describes as being quasi-provinces of China.

"The Fight for Influence: Russia in Central Asia" by Alexey Malashenko. Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2013.

Contact the author at g.golubock@imedia.ru

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.