What is President Vladimir Putin's next move? The answer is thus far undecided, perhaps even for Putin.

To put ourselves in Putin's shoes, Western observers and analysts have searched history for analogous moments in time. Historians tell us that if we can find similar historical circumstances, we might be better able to predict what will happen next. Some experts look to 1914 and the run-up to World War I for clues and insights.

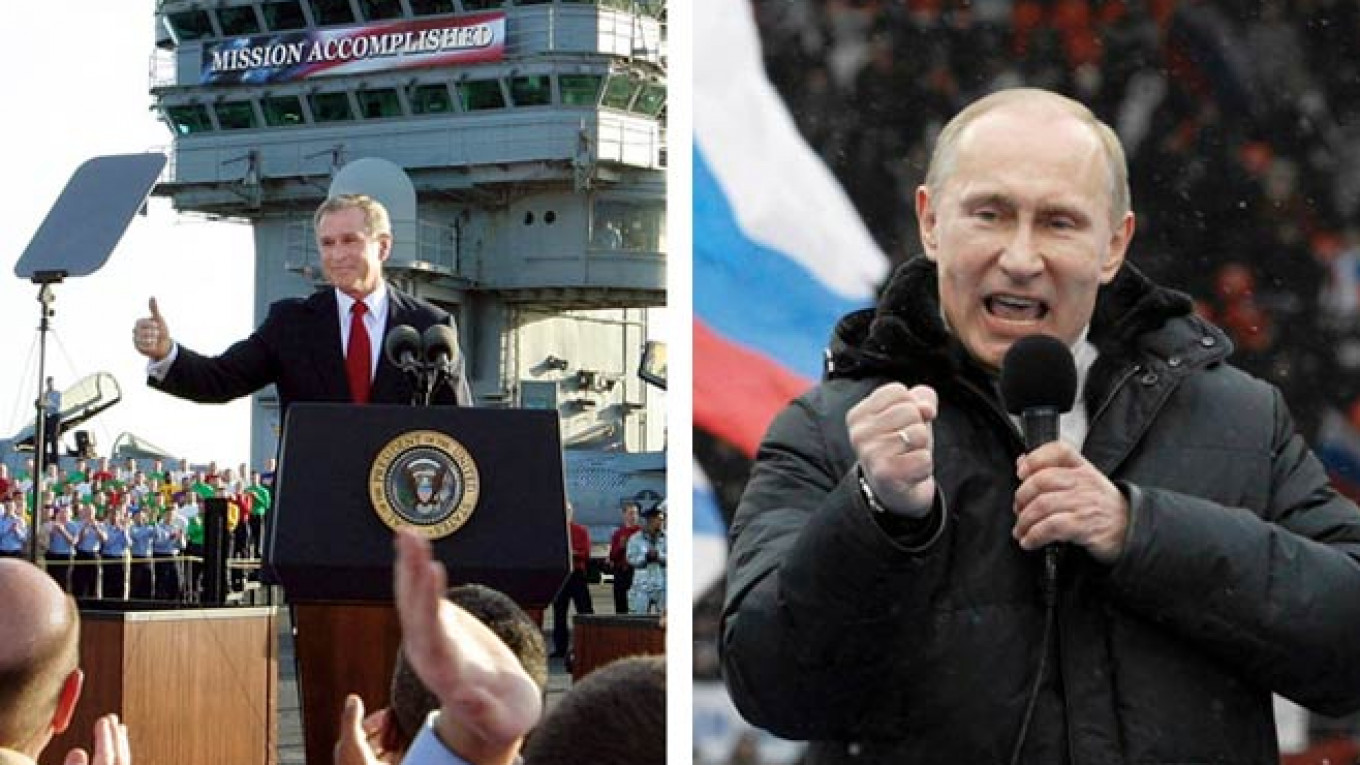

But for Putin and his inner circle, the most analogous moment in history is December 2001. Russia is playing the role of the U.S. as it basked in the initial "success" of Afghanistan and contemplated Iraq. The parallels are uncanny.

Today, flush from a stunning and rapid victory in Crimea, largely at the hands of special forces and intelligence services, Putin has mobilized and deployed a professional army, ready to fulfill his next orders. There is no opponent who stands in the way of a military adventure into Ukraine.

With an approval rating hovering above 70 percent, Putin is buoyed by almost universal support from Russians and elites for what he has done thus far. In the domestic narrative, he has swept into Crimea to protect the people from what some Russians are already calling the "Ukrainian Taliban" — West-leaning protesters and opposition forces that include some extremist activists. He is now prepared to extend the same "protection" to other ethnic Russians in eastern Ukraine — and maybe elsewhere.

Should Putin do the safe thing and pocket his easy victory, or should he "go long" and attack a problem that has been a stone in Russia's boot since 1991 — Ukraine?

Putin's dilemma is whether to use his current advantage to change the game inside Ukraine once and for all to Russia's advantage. This is a choice very similar to the one U.S. President George W. Bush faced as he contemplated stretching his early success in Afghanistan into a game-changing victory in Iraq.

The Russian military that is now positioned along the Ukrainian border is certainly the most capable force the country has mustered since the Cold War. According to the commander of NATO forces, U.S. General Philip Breedlove, there are 40,000 Russian troops deployed along Ukraine's border, a combined arms force "capable of attacking on 12 hours' notice."

Social media and open media reports clearly show elite combat brigades from Moscow-based rifle and tank divisions as well as the country's rapid reaction airborne paratrooper units. Russian special forces units and covert agents are reported to be operating throughout eastern Ukraine, helping pro-Russian protesters destabilize the Ukrainian government. Putin can realistically take most of Ukraine by force, or he can wait for the country to fall apart in front of him.

But what would be the downside of such an acquisition? Whoever "wins" Ukraine inherits a nesting doll of problems, one inside another. There is the economic mess that will cost billions to clean up, a corrupt political system that even Putin jokes makes his oligarchs seem honorable by comparison. What's more, someone will have to sort out the core of Ukraine's sorrow: the ethnic antagonism between Ukrainians and Russians.

In the run up to the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, Sergei Ivanov, then-defense minister, cautioned his U.S. partners in the war on terror that they risked squandering their earlier successes in Afghanistan for a myriad of problems in Iraq. I was the U.S. defense attache in Moscow at that time and the conduit for many admonitions to beware of strategic overreach in Iraq. Does Ivanov have similar advice today for his boss with regard to Ukraine? It must certainly be on his mind.

There are of course many differences between December 2001 and today. For one, the reasons for military action in Afghanistan and Crimea are completely different. Another difference is that Russia supported the U.S. in the fall of 2001, while the U.S. and the West oppose Russia's actions now. Nevertheless, there are undeniable similarities.

The fundamental question facing Putin today is essentially the same one that faced Bush in his time: Where does bold initiative end and reckless overreach begin?

Brigadier-General (Ret.) Kevin Ryan is director of defense and intelligence projects at Harvard Kennedy School's Belfer Center and former U.S. defense attache to Moscow.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.