Events in Ukraine have taken an ominous course. One by one, cities and towns in the Donbass are being taken over by small groups of well-organized armed forces, which have occupied administrative headquarters and police stations. The interim government in Kiev utters protests and threats but thus far has largely failed to dislodge the intruders.

Who are these people, who leads them, and what are their goals?

Although many in eastern Ukraine opposed the Maidan protests, they do not have separatist sentiments.

The reports circulating on social networks suggest that they comprise both people from outside the region and within and that is a well-planned operation exploiting local forces to undermine the authorities in Kiev and disrupt the presidential election on May 25. The bloodiest confrontations have taken place in smaller towns in the region, such as Slovyansk, Kramatorsk and Horlivka.

Sometimes foreign presence is clearly evident, as in Kharkiv when protesters initially took over the Opera House rather than the government building. Residents of towns reported gangs roaming streets, speaking in Russian accents, mocking or assaulting local citizens. The central squares of many towns are unsafe, especially at weekends when these gangs operate.

At the same time, Russia, Ukraine and the West are engaging in a battle of rhetoric and propaganda. The Russian leadership insists that the government in Kiev is a "right-wing junta" that wants to discriminate against Russian speakers. Kiev believes there are some 2,000 Russian special agents carrying out subversive activities in Ukraine.

Concerning the presidential election next month, the consensus is that Russia would much rather see a victory by former Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko than oligarch Petro Poroshenko. Tymoshenko has spoken out against the use of force to remove those who have taken over government buildings. Acting President Oleksandr Turchynov had issued a futile ultimatum for separatists to lay down their weapons, which expired on April 14.

While the Ukrainian economy continues its tailspin, aid from the International Monetary Fund, the European Union and the U.S. may not be enough to avert default. Russia has raised its gas prices to Ukraine by 80 percent and claims that Ukraine owes some $35 billion in gas debts to Russia. Moscow will likely demand that Kiev makes future gas payments in advance, further exacerbating Ukraine's economic problems.

A large portion of residents in Crimea opposed the Euromaidan, but eastern Ukraine is much more polyglot, where many families are of mixed Ukrainian-Russian heritage. Most have accepted life in an independent Ukraine and do not have separatist sentiments.

The country's powerful oligarchs have nurtured their own fiefdoms free from the influence of powerful Russian satraps to the north. Virtually the entire Cabinet in the former administration of President Viktor Yanukovych came from Donetsk. Their displacement leaves a vacuum, with the once-powerful Party of Regions now largely outside the interim state structures.

Dmytro Yarosh, the leader of the ultranationalist movement Right Sector, is wanted in Russia for "terrorism." Yarosh and others were key figures in the escalation of violence at Euromaidan. He demands that the Party of Regions and Communist Party be banned and wishes to remove all "foreign influences" from Ukraine. Yarosh also intends to run for president, but he is a marginal figure at best with no chance of winning the race. Kremlin propaganda loves to speak of the "fascist threat" coming from Right Sector and Svoboda party, but their influence on Ukraine's political landscape is greatly overblown.

But Russia's leaders would prefer Yarosh to remain prominent because he is a useful bogeyman. Above all, they want to prolong in power the weak and ineffective government led by Turchynov and acting Prime Minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk.

Meanwhile, the 50,000 Russian troops massed on the border with Ukraine are heightening tension and could bully Ukrainian leaders into making concessions, such as a promise of federalism for the Donbass. Putin is less motivated by economic factors than by immediate political gains.

Putin's strategy is not to invade the eastern regions, if possible, but to turn them into mini-states that are autonomous from Ukraine and linked to Russia more closely. Russia may be perceived by many Russian speakers in the region as a haven of stability, of employment and higher wages, and free from the sort of chaos and mayhem brought by Euromaidan. Similar scenarios could be played out in the south, from Kherson to Odessa, and encompassing the self-proclaimed Transdnestr republic in Moldova.

What will become of Ukraine? Putin wishes to control it as fully as possible, to ensure that it remains firmly within Russia's orbit. Thus it would not be a major concern whether the next government in Kiev is pro-Russian. Options are open. And it is the range of possibilities that may confuse the "enemy"— NATO, the EU or the interim government of Ukraine—but they are all integrated into one current plan, which might be defined as to "disrupt, undermine, intimidate and cause chaos" all backed by a formidable wave of disinformation.

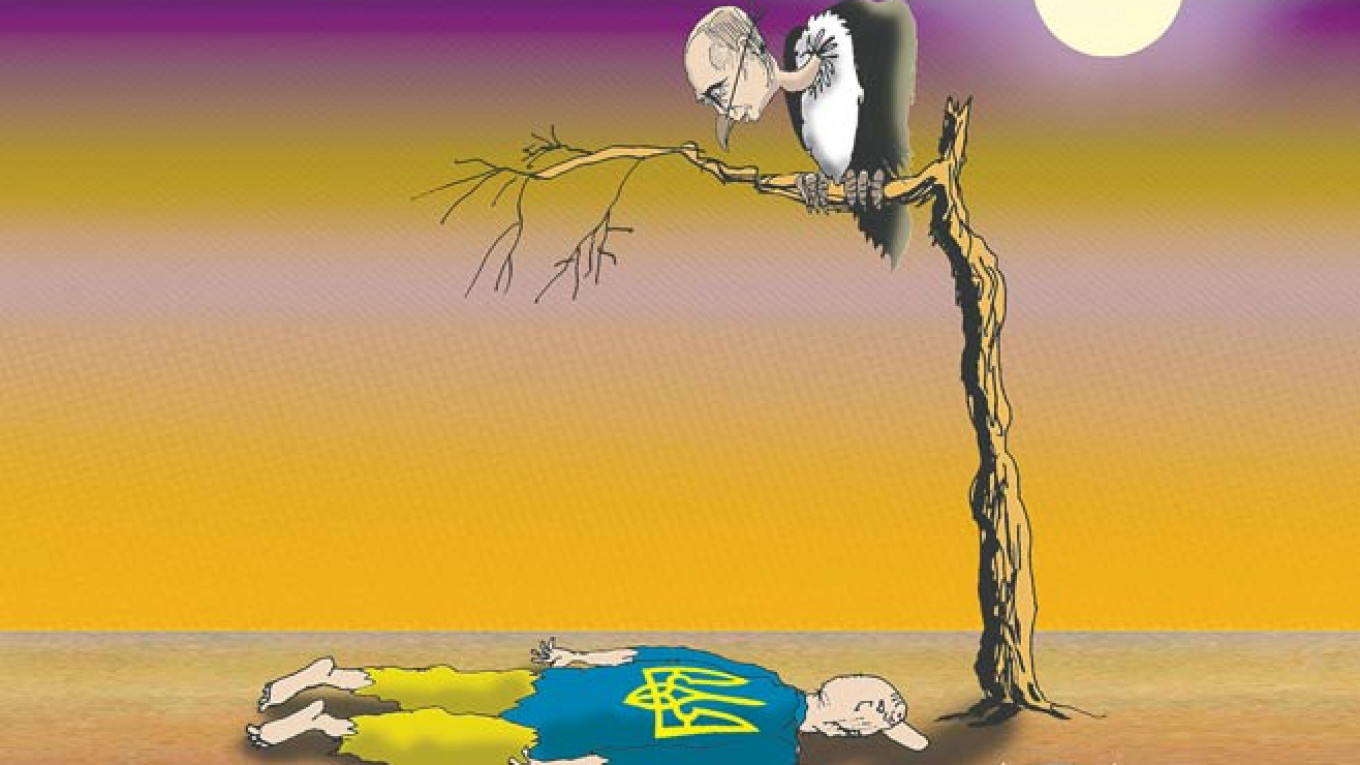

Putin is not only destabilizing Ukraine. He is destroying whatever democratic elements have remained in Russia. But at present, what is more important than democracy to many Russians is the reassertion of the country's position in the global arena. For the moment, Ukraine is like carrion, slowly picked apart by marauding crows while passersby shake their heads in concern — but can do little to prevent them.

David Marples is a distinguished university professor at the University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.