This may not end up being my best column, but it will be one of my personal favorites. It has no real plot and very little dramatic line. It does, however, have a couple of heroes and don't we all love a hero?

My wife and I attended a performance of Lev Dodin's production of "An Enemy of the People" at the Maly Theater on Tuesday evening. Before the show we ran into my friend Maxim Osipov, who was there with his daughter. We exchanged pleasantries and headed our separate ways. We exchanged nods again at intermission and, after the show, once again shook hands, smiled and offered each other genteel farewells as we, again, headed in different directions.

I told you it was a slow-moving story. Some stories are.

And as long as I put the brakes to the telling of the tale, let me pause another moment to introduce you more closely to Mr. Osipov.

Maxim Osipov is a living reproach to the rest of us mortals. If you, like I, have ever begged off an invitation or a request because you are "too busy"; if you ever failed to do something you promised to do because your schedule is overloaded; or if you have ever called out to the gods, "Why, oh, why is time so short?" — don't bother complaining to Osipov.

This man wears a cape when you're looking in the opposite direction. He has webbed fingers half the day. He shoots sticky spider-web stuff out of his finger nails when necessary. You get the point. Super-human.

You see, Maxim Osipov is not just a practicing cardiologist, not just the author of an important textbook called "Echocardiography," not just a publisher of medical literature — his Practica publishing house was a leader in the field from 1993 to 2010 — he is the head of a charitable fund that saved the city of Tarusa from losing its hospital.

Big deal, you say? So he's a doctor. So he's a scholar. A publisher. A philanthropist. So he saved a city from losing healthcare. He hasn't moved you yet? Well, add this to the mix: Maxim Osipov — the same Maxim Ospiov — is one of the most respected writers to have emerged in Russia in recent years.

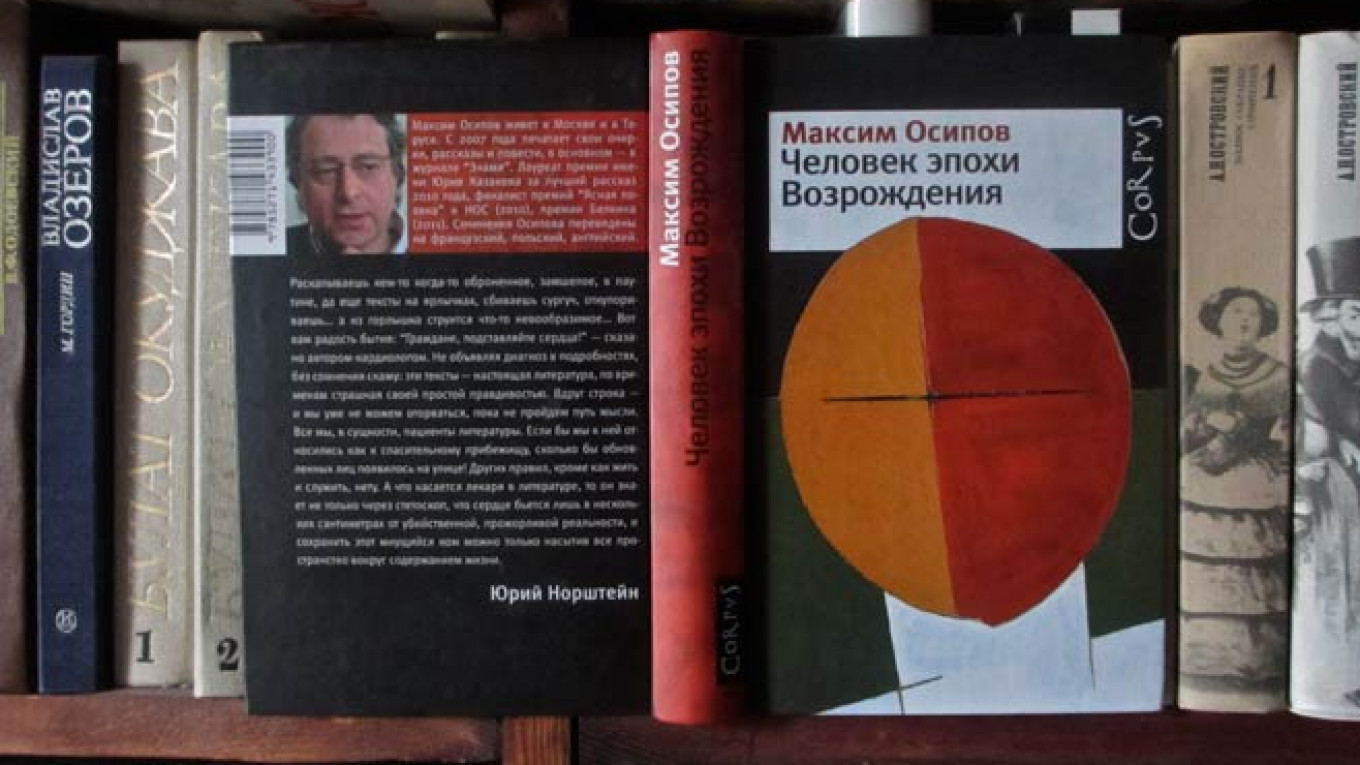

That's right. He's the author of three collections of novellas and short stories that have grabbed high praise indeed. Yury Norshtein, the celebrated Russian animator, declared Osipov's tales "true literature, at times terrible in their simple honesty." A fourth collection is coming out just weeks from now.

Still not enough? His play "Russian Language and Literature" has been staged in Omsk and at Lev Dodin's Maly Drama Theater in St. Petersburg. Another play, "Scapegoats," was recorded as a radio play by the Culture channel.

In short, add the name Osipov to that extraordinary line of Russian doctor-writers that includes folks like Anton Chekhov, Mikhail Bulgakov and Vasily Aksyonov.

But the story, the story, you say. Here's the story.

After parting ways with the doctor-writer I headed upstairs at the Maly Theater to retrieve my wife's coat. Instead, I found what clearly appeared to be a dead man lying on the floor near a doorway. A small crowd had gathered and most everyone looked as confused as they were worried.

I ran back to find my wife who was busy chatting cordially with friends. I butted in rudely and played the moment for all the drama I could muster.

"Have you seen Osipov?" I asked. "There's a man dying upstairs!"

My wife's friends backed off in shock, and my wife, the actress Oksana Mysina (information required for a subsequent twist in the tale), immediately headed up the stairs.

"Where are you going?" I shouted. "You can't help! Where's Osipov?!"

Oksana disappeared and I began running around the theater looking for the doctor. He was nowhere to be found. I ran out onto the street between the Maly and Bolshoi theaters and I began shouting at the top of my lungs, "Maxim Osipov! Are you still here!? Maxim Osipov! Maxim Osipov!" I got plenty of strange looks and a lot of people made wide berths going around me, but there was no Maxim Osipov to be found.

Devastated, I went back into the theater and hurried up to the second floor where I had last left a man dying. There, to my thrilled amazement, I saw two figures leaning over the lifeless man, one squeezing his hand tightly — that was my wife — the other talking to him, asking questions and trying to get him to respond — that was Maxim Osipov.

Afterwards I asked the doctor how he found out about the fallen man.

"I just happened to walk by," he said.

"That's a professional nose if ever there was one," I said.

But before that little exchange took place, Doctor Osipov had to bring his patient around. He did so in a matter of minutes. I sat 100 feet away, happily perched on a red velvet stool, hugging my briefcase, listening to the good doctor do his work.

He asked the ailing man how old he was, but the man could not say. He did remember quickly that he was born in 1937. It was then that he looked up at my wife and squeezed her hand tight again before saying, "I know you. You're Oksana Mysina. I thought you looked familiar."

Oksana smiled. What actor isn't pleased to be recognized? Especially by someone coming back from a little trip to the other side.

"And your husband," the patient said, still lying prone on the floor but with his feet now propped on a chair thanks to Doctor Osipov, "is an American."

Now I was laughing. This guy was going to make it.

Oksana tried to get him to pay attention to Doctor Osipov again.

"This is a famous doctor," Oksana told him. "You need to listen to him."

The man gave no response.

"And he's a famous writer, too," Oksana added.

"Oh, I don't care," the man scoffed. "Everybody's a writer."

Everybody may be a writer, but I suspect only a chosen few become doctors. When an ambulance arrived 15 or 20 minutes later, the team of medics confirmed what Doctor Osipov had already determined. His patient had suffered complete heart block. That is, his heart had stopped. He had died. And he came back to life under Osipov's timely treatment.

As Oksana and I left the theater, the man was sitting up and being a typical mutinous patient. He refused to go to the hospital, didn't want to answer questions, and insisted nothing was wrong with him. It was enough to warm the cockles of your heart.

Hey, Doctor Osipov! I wonder if Maxim might find a story in this?

Contact the author at jfreedman@imedia.ru

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.