A sleeping man is taken for a corpse by a policeman. A Russian rock icon demands change. Civilization as we know it is wiped out by a nuclear blast. These disparate scenes represent a sliver of the variety and inventiveness of late Soviet film, the subject of “Cinema of Change,” a new program now underway at Moscow’s Cinema Museum.

The cinema of the perestroika era is less well-known in the West than that of the revolutionary period or Khrushchev’s Thaw. By the time Mikhail Gorbachev initiated the programs that would, in turn, open up, destabilize, and bring down Soviet society, Andrei Tarkovsky was already in exile and Alexander Sokurov was still a whispered-about young nonconformist in Leningrad. Nevertheless, as Gorbachev’s glasnost expanded artistic freedom and the future began to appear progressively more uncertain, Soviet cinema entered one of its most urgent and diverse periods.

According to Alexei Artamonov, a press secretary at the Cinema Museum and one of the organizers of the program, “political censorship fell away, and filmmakers finally had the possibility to ask questions sharply and directly, and to honestly grapple with not only the Soviet past, but the present as well.” Indeed, one consequence of Gorbachev’s attempts to introduce glasnost, or transparency, to Soviet society was to give Soviet artists more freedom than they had enjoyed in a generation. “Many perestroika films were known as the ‘cinema of social discomfort,’” Artamonov said to The Moscow Times via e-mail, “and their social diagnoses were indeed quite sharp.”

Konstantin Lopushansky’s “Letters From a Dead Man” (1986) is just one film to express a viewpoint that would have been unacceptable under Leonid Brezhnev. Taking place after an accidental nuclear holocaust, it presents Soviet militarism in a light far removed the conventionally rosy treatment of Red Army. However, Lopushansky largely bypasses contentious topical issues in favor of abstract ones, and much of the film takes the form of an extended rumination on mankind’s seemingly endless capacity of self-destruction.

Stuck in the wreckage of an art museum, the film’s characters, largely scientists and intellectuals, pontificate and argue, cling to life, perish, and off themselves. The film’s dilapidated, sepia-toned aesthetic alternately recalls deteriorating silent films, newsreel footage, and the first thirty minutes of Tarkovsky’s similarly philosophical sci-fi film “Stalker” (1979), on which both Lopushansky and co-screenwriter Boris Strugatsky also worked. Veteran Soviet actor Rolan Bykov stars as the author of the titular letters, an ex-scientist whose sad, wizened gaze adds some very necessary pathos to the rubble and discourse. It is very much a film of its time, striving toward lofty humanism and dedicated to the Committee of Soviet Scientists for Peace, Against the Nuclear Threat.

A rather more youthful tone is taken by Sergei Solovyov’s self-consciously postmodern “Assa” (1987). In many ways a document of the semi-illicit Soviet youth underground, the film literally annotates itself, stopping the action to give text definitions of slang. For good measure, the audience is also treated to Russian rock numbers, experimental dream sequences, flashbacks to the time of Paul I and an inexplicable black character — ostensibly the son of Angolan Marxists — who does not resemble an African so much as a bearded Russian man who happened into a chimney.

The plot, a romance no more complex than that in Jean-Luc Godard’s “Breathless” (1959), a clear model, does not seek to unite these tendencies so much as to hold them together as if in a sort of gelatin. In short, a girl meets a guy, played by Sergei “Africa” Bugayev, a mainstay of the Russian underground and associate of John Cage, Gus Van Sant, and, eventually, Vladimir Putin. Eventually, her gangster boyfriend arrives, leisurely leading to an inevitable confrontation. Indeed, the film’s unhurried pacing and oversaturated, hazy widescreen compositions of a snowbound Yalta give it a dreamy, melancholic gravitas that rubs against its youthful energy. This counterpoint runs through the whole film, until the closing number, Viktor Tsoi’s “Change,” which became something of an anthem for hopeful youth.

However, as perestroika wore on and the Soviet Union slid further toward its eventual demise, the national mood changed. According to Artamonov, “starting in 1988, the euphoria of glasnost began to turn into a sensation of depression and disappointment.” It was into this gloomy atmosphere that Kira Muratova, a mercurial iconoclast and perpetual fly in the censor’s ointment, unleashed Soviet cinema’s nastiest masterpiece.

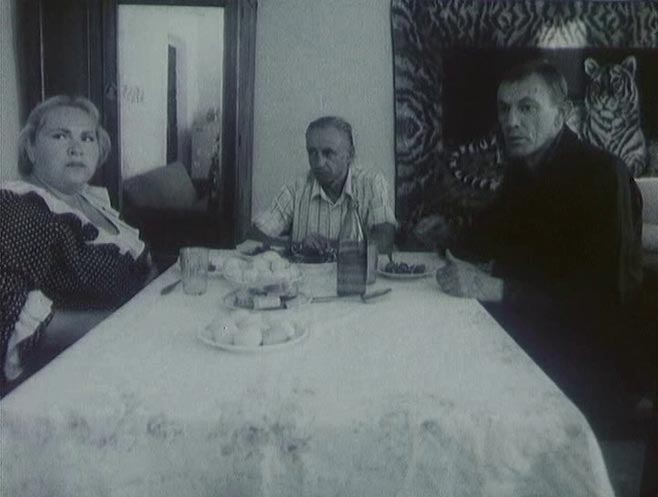

If other black comedies, like “Dr. Strangelove” or “Fargo,” make humor out of dark or depressing subject matter, “The Asthenic Syndrome” (1989) is the rare movie bold enough to make comedy out of sadness itself. The films begins bracingly enough, with the washed-out black-and-white story of a woman who devolves into prolonged, anti-social rage following her husband’s death. After a good 30 minutes, this is revealed to be a film-within-the-film, and the lights come up on our new hero, Nikolai, a hapless Gogolian schmuck who suffers from indifference and sleepiness. Alongside our unsettlingly passive hero, we drift through a world of unfailingly hostile grotesqueries and malcontents, stopping by a dusty roadside fish market, a dog shelter, and an nudity-laden underground film shoot. At no point does Muratova deign to imply that any of this has much of a future.

The film is given shape less by its plot, which is scant, than by compulsive fluctuations between tonal extremes. Long, static episodes are followed by aggressive, manic ones, making for a viscerally abrasive viewing experience. For a film about numbness, “The Asthenic Syndrome” packs quite a sting, but Muratova is not merely trying to make her audience squirm. As the title implies, it is a diagnosis of a society’s malady, and, maybe, a shot to the heart. While it is certainly not the most beloved or accessible of all great Soviet films, “The Asthenic Syndrome” is, fittingly, perhaps the last.

As Russia adopted capitalism, the Soviet filmmaking system struggled to stay afloat, eventually tumbling into what Artamonov deems “total decline.” By the time Russian filmmaking recovered in the late 1990s, the film culture of the perestroika era had receded into history. Though their legacy and influence have yet to be defined, watching these films can still be a powerful and surprising experience.

The Cinema Museum’s “Cinema of Change” continues at Mossoviet Theater through March 30. Among the upcoming films are Alexander Kaidanovsky’s phantasmagoric “The Gasman’s Wife” (1988), Vitaly Kanevsky’s autobiographical “Freeze Die Come to Life” (1989), winner of the Camera d’Or at the 1990 Cannes Film Festival, and Nikolai Dostal’s lighter, allegorical “Cloud-Paradise.”

Contact the author at artsreporter@imedia.ru

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.