Национал-предатель: "national traitor," fifth column

As is my wont, I watched President Vladimir Putin give his "Crimea speech" and then printed it out to study linguistically. At first I thought there was nothing to say. This is not the kind of speech you scour for hints of mood or intention. It telegraphs mood and intention.

But then I realized it is very different in tone than any other speech Putin has given. There are, of course, stylistic flourishes he has used before, like the high pathos of "В сердце, в сознании людей Крым всегда был и остаётся неотъемлемой частью России" (In people's hearts and minds, Crimea has always been and will always be an integral part of Russia).

And there's his typical sarcasm about the West, like "Нам говорят, что мы нарушаем нормы международного права. Во-первых, хорошо, что они хоть вспомнили о том, что существует международное право" (We are told that we are violating international law. First of all, it's good that they have at least recalled that there is such a thing as international law). And some pointed digs at the "национал-предатели" (national traitors) at home.

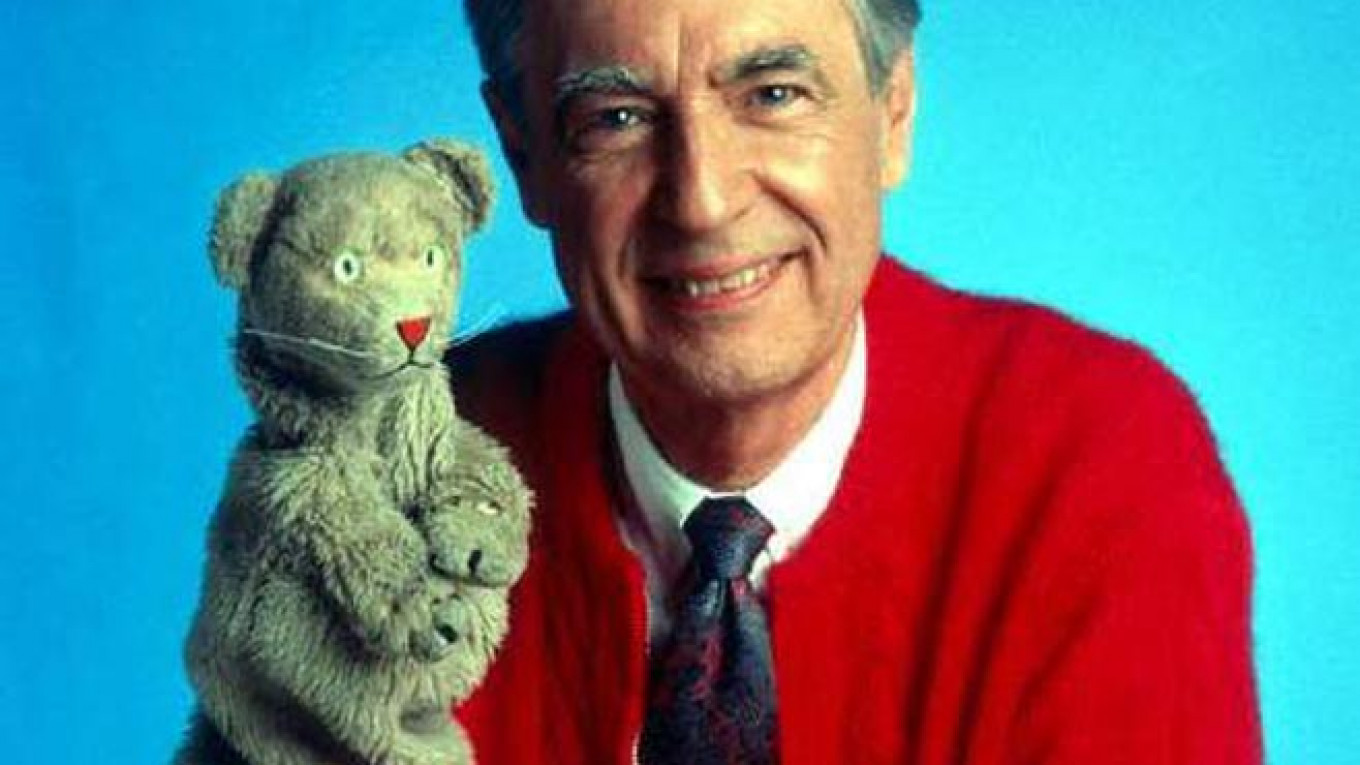

But despite the key message of strength and defiance, almost all of the speech is written from a "gee-whiz, gosh-oh-golly" pose. It is as if the president were trying to channel Jimmy Stewart in "Mr. Smith Goes to Washington." Or become Mister Rogers, explaining life as he sings: "It's a beautiful day in this neighborhood, a beautiful day for a neighbor." But Putin is just not a gee-whiz-gosh-and-golly kind of guy. Tone and message were at odds.

When he was not asserting Slavic glory, he was coyly asking questions and answering them. In describing Crimea's status as part of Ukraine after the breakup of the U.S.S.R. he says: "Ну, что Россия? Опустила голову и смирилась, проглотила эту обиду" (And what did Russia do? She put her head down and accepted the situation humbly, swallowing the insult).

And then: Из чего мы тогда исходили? Исходили из того, что хорошие отношения с Украиной для нас главное, и они не должны быть заложником тупиковых территориальных споров.(What did we base our actions on? On the fact that good relations with Ukraine were the most important thing for us, and they should not be hostages to dead-end territorial disputes.)

His stance was either "don't mess with us" or "poor little us," mistreated by the West. "Россия искренне стремилась к диалогу с нашими коллегами на Западе" (Russia sincerely wanted dialog with our colleagues in the West).

He explained things in simple phrases we could all understand. This was Mister Rogers doing mansplaining about Ukraine — but apparently not Russia: "Права на мирный протест, демократические процедуры, выборы для того и существуют, чтобы менять власть, которая не устраивает людей" (The right to peaceful protest, democratic processes, and elections exist solely to replace leaders who don't satisfy people).

But sometimes Mister Rogers' "facts" were contentious, even if his tone stayed simple. In Ukraine, he said, "В ход были пущены и террор, и убийства, и погромы. Главными исполнителями переворота стали националисты, неонацисты, русофобы и антисемиты." (They resorted to terror, murder and pogroms. The coup was led by nationalists, neo-Nazis, Russophobes and anti-Semites.)

I know the crowd roared at every assertion of greatness. But forgive me — I kept hearing Mister Rogers: "Since we're together, we might as well say, Would you be mine? Could you be mine? Won't you be my neighbor?"

Michele A. Berdy, a Moscow-based translator and interpreter, is author of "The Russian Word's Worth" (Glas), a collection of her columns.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.