In response to Russia's intervention in Crimea, a powerful anti-Russian discourse is spreading across Western media. Russia's actions are compared to those of Nazi Germany, which incorporated Austria in 1938 before breaking up Czechoslovakia and igniting a World War. The implication is that the West must not follow France's and Britain's 1938 example by appeasing an aggressive Russia and that only tough actions may stop President Vladimir Putin from further expansion into Ukraine or even beyond.

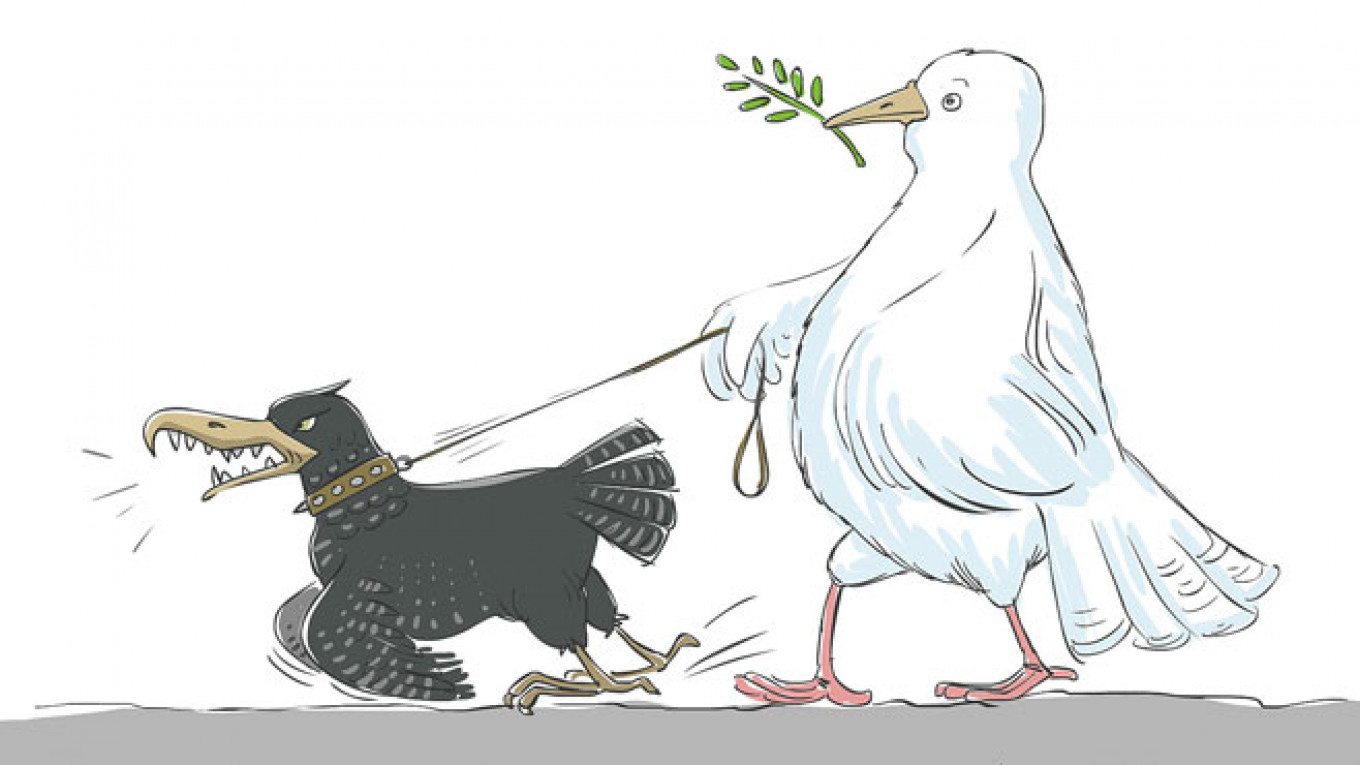

The hawks who say it is dangerous to appease Putin are trying to push the U.S. toward a military conflict with Russia.

In the U.S., politicians as different as Senator John McCain and former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton have endorsed the appeasement theory. Those with nationalist Eastern European roots, too, have been vocal in applying the theory to Russia. For example, writing in The Guardian, former Georgian President Mikheil Saakashvili darkly warned that "the cycles of appeasement usually get shorter with geometric progression" and that the longer Putin stays in power, the sooner he will be likely to "strike again."

We have watched this play before when those who stood in the way of U.S. hegemony were being compared to Hitler. First, it was former Serbian leader Slobodan Milosevic who refused to follow the U.S.-negotiated peace accord. Then came former Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein, who was accused of building nuclear weapons and conspiring with al-Qaida, none of which proved true. Unsurprisingly, Libya's Moammar Gadhafi and Syria's Bashar Assad were also compared to Hitler. Each time, the vision of a "bloody dictator" and "murderous thug" was heavily publicized in the Western media with the implication that the U.S. must urgently confront the aggressor and save global civilization from horrors of another holocaust and World War.

None of these dictators elicit any sympathy, of course. Yet in each case, the comparison with Hitler was vastly overdrawn. Far from being Hitlers, they were regional strongmen with ambitions to control their own country by suppressing opposition. Although their foreign policies had a potential to destabilize their regions, none had an explicit expansionist design. Although the U.S. has no vital interests in those regions, it should speak out against gross violations of human rights. But it should have employed concerted diplomatic actions to address them. Instead, a regime change strategy was adopted. As a result, democracy was associated with putting a U.S.-friendly regime in power rather than supporting democratic processes. As to those daring to oppose the U.S.' global agenda, they risked to be isolated at best — and killed at worst.

The appeasement logic suffers from two important flaws when it is applied to Russia. First, it wrongfully presents the U.S. policy toward Russia as true engagement. In reality, the West never tried engagement. Because of deep mistrust toward Russia, U.S. policy was a combination of selective cooperation and a large dosage of containment. Take, for example, NATO expansion toward Russia's borders and a refusal to incorporate Russia into the West's security framework. By proposing to stand tough with Putin now, appeasement advocates want to apply hardline measures aimed at Moscow that have caused so many problems with Russia in the first place. The hawks around Putin would only be grateful for Western pressures as a justification for ratcheting up its anti-U.S. and anti-Western rhetoric and propaganda. In the meantime, this toughness on both sides could easily escalate to a military conflict.

The appeasement theory also misreads Russia's motives in Ukraine. As in Georgia, these motives are related to preservation, not expansion, of the Kremlin's influence. Humiliated by the West's containment strategy and the collapse of the agreement of Feb. 21 between the Ukrainian government and the opposition, Putin used Crimea as a bargaining chip in negotiating the restoration of Russia's influence in Kiev. Yet, while his ambitions are limited, Western military pressures may push Putin to intervene in eastern and southern Ukraine.

Those applying the appeasement metaphor to Putin want to sabotage the Western leaders' attempts to resolve the Crimea crisis through diplomacy. In reality, they want to push the U.S. toward a military confrontation with Russia. They are making their case in Western media because the appeasement argument, as history shows, is more likely to convince the public to support the war against a global aggressor. There is reason to believe that the majority of Americans will not fall for this tactic. They have, after all, learned tough lessons over the past 20 to 40 years of U.S. interventions in other countries.

Whatever McCain, Clinton, Saakashvili and their supporters have to say, the solution to the Ukrainian crisis is to work out conditions respectful of Kiev and Moscow's wishes, not to drum up the war rhetoric. Washington and Brussels should continue to look for a diplomatic solution to the Russian-Ukrainian conflict and not yield to the pressures of anti-Russian hawks.

Andrei Tsygankov is professor of international relations and political science at San Francisco State University.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.