The world is not a peaceful place, and many of the problems are directly related to Russia. Still, besides the predictable topics of the Sochi Olympics and the turmoil in Ukraine, Russian politicians and what seems to be thousands of ordinary Russians have been focused on the fate of two young giraffes, both named Marius, in Danish zoos. One was killed by zoo officials to prevent inbreeding; the other seems to have avoided such a fate, at least for now.

While the killing of the first Marius led to protests by animal rights defenders in the West, apparently it was only in Russia that the defense of giraffes reached such a high level and prompted such high-pitched public indignation. Indeed, the conservative Zavtra newspaper published pictures on its front page of the young giraffe with what looks like an innocent teenage boy. The headline read, "They Killed Marius!"

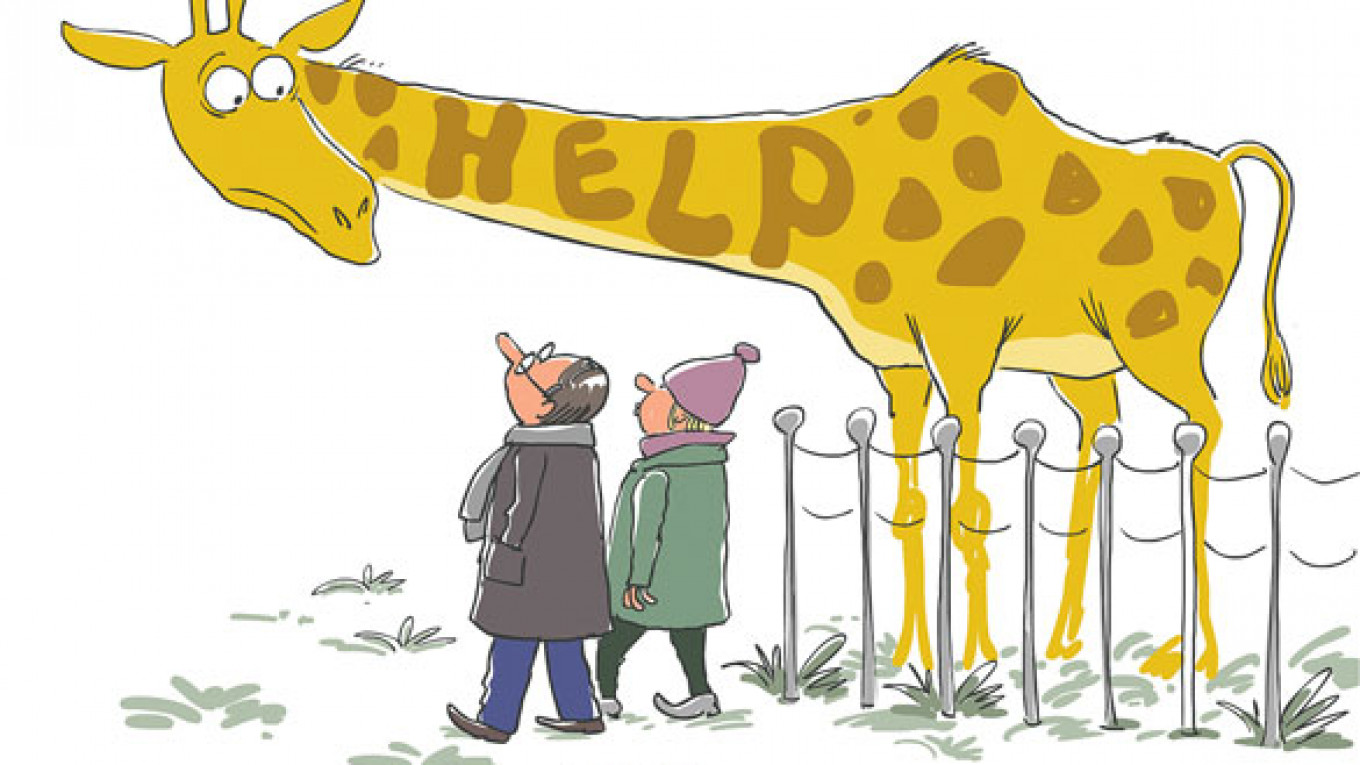

Choosing animals as dissidents could open a most exciting and promising era in world politics.

Natural Resources and Environment Minister Sergei Donskoi expressed indignation as did Vitaly Milonov, the St. Petersburg lawmaker known for drafting the city's anti-gay law. Finally, Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov proposed bringing the second Marius to Chechnya, where he promised him a comfortable place in the zoo and good medical treatment.

Why such an interest in the fate of a giraffe?

The interest in the two Marius' fate in present-day Russia — which is mired in a conflict with both the U.S. and Europe on issues ranging from Ukraine to the treatment of gays — has an underlying reason. Understandably, both Russia and the West are engaged in a choice of noble dissidents mistreated by the other. In Russia, this tradition has a long history. When the West accused the early Bolshevik regime of terror, for example, they pointed to France's treatment of defeated Communards in 1871. Sacco-Vanzetti, who anarchists accused in the killing of a security guard and paymaster in a shoe factory in the U.S. in 1920, became the symbol of capitalist brutality and hypocrisy, and a pencil factory in Russia was named after them. I personally remember using the products of this factory during my school years.

Later, in the 1960s, the victim became Angela Davis, a member of the Communist Party in the U.S. The fact that she later became a professor at a prestigious American university was conveniently ignored.

During the early post-Soviet era, when both Russians and Westerners had their own illusions about their relationship, there was no need to search for noble dissidents. The need for noble dissidents resumed with the recent cooling of Russia's relationship with Washington and Brussels.

Russia has had a problem finding a good example with whom to take a moral stand. It is true that President Vladimir Putin himself presented a Russian passport to Gerard Depardieu, the famous French actor known to Russians for his title role in "Danton," Andrzej Wajda's drama about the Reign of Terror following the French Revolution. But Depardieu did not flee from the tyrannical rule of a new Robespierrian government plainly because he did not want to pay high taxes. U.S. intelligence leaker Edward Snowden seems to be another good choice for Kremlin acclaim. But accepting Snowden as a freedom fighter would imply that any Russian intelligence operative who would run to the West would be honored as a hero. The Kremlin is hardly pleased with such an idea. As a matter of fact, it was clearly pleased with the death of Alexander Litvinenko, who worked for Russian intelligence and died after a mysterious illness in London.

So here the dead Marius has become a godsend. It was an innocent animal. By killing it, the West, including Europe, has shown its hypocrisy because a humane approach to animals has been proclaimed as a major Western virtue.

But should the Westerners or anybody else resist Russian hopes to save the second young giraffe? Of course not. Actually choosing animals as dissidents could open a most exciting and promising era in world politics. The choice of dissident among nonhumans has clear advantages for both the country from which the animals depart to the country of their final destination. Marius, for example, did not divulge any military or political secrets. It did not criticize its previous place of residency as an abode of cruelty and persecution and the zookeepers as brutes who also violated its rights in front of television cameras. The giraffe will not demand from a new master a lavish pension, a mansion and other benefits. It is content with a little space to walk and a few bundles of hay and shelter, which any budget, even after the most serious sequestration, could afford. The giraffe did not embarrass the zookeeper with homesickness, depression and loneliness. It did not need even a mate to be happy, as one Russian commentator noted. Harmless and peaceful, Marius, if actually transplanted to Russia, would not become a symbol of tension as is the case with human dissidents but rather a messenger of peace.

Indeed, young Marius could remind us that we share not only the same planet with animals but also the same fate — mortality.

Dmitry Shlapentokh is an associate professor of history at Indiana University, South Bend.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.