Two weeks ago, the 7:25 a.m. train from one of London's outer eastern suburbs screeched to a halt near the Liverpool Street station located in the heart of the financial district.

It soon emerged that the reason for the stop was because a person had jumped in front of the 7:20 a.m. train just ahead.

Rather than having sympathy for the individual who was driven to such a desperate act, the passengers took to Twitter to condemn the lack of consideration for those now late for work. Several tweets expressed satisfaction that, making an assumption based on the location, at least the world was rid of one banker.

According to newswire searches, similar scenes are enacted frequently on that train line and on similar lines into rail stations in New York, Tokyo and other major financial centers.

It is bonus season in the financial industry.

This is the ugly side of working in financial markets, where people become used to a culture where winning is everything and where the line between the vast sums of money they deal with on a daily basis and real life often becomes blurred. The view that most people have of those who work in financial markets is framed by such movies as the recently released "The Wolf of Wall Street" and the 1987 "Wall Street," whose synonymous refrain, "greed is good," became the motto for a generation of bankers and traders.

But after the collapse of Lehman Brothers in September 2008 marked the start of a global financial and economic crisis, "greed is bad and so is anyone working in the industry" has become a popular catchphrase in the media and among politicians and pretty much everybody else.

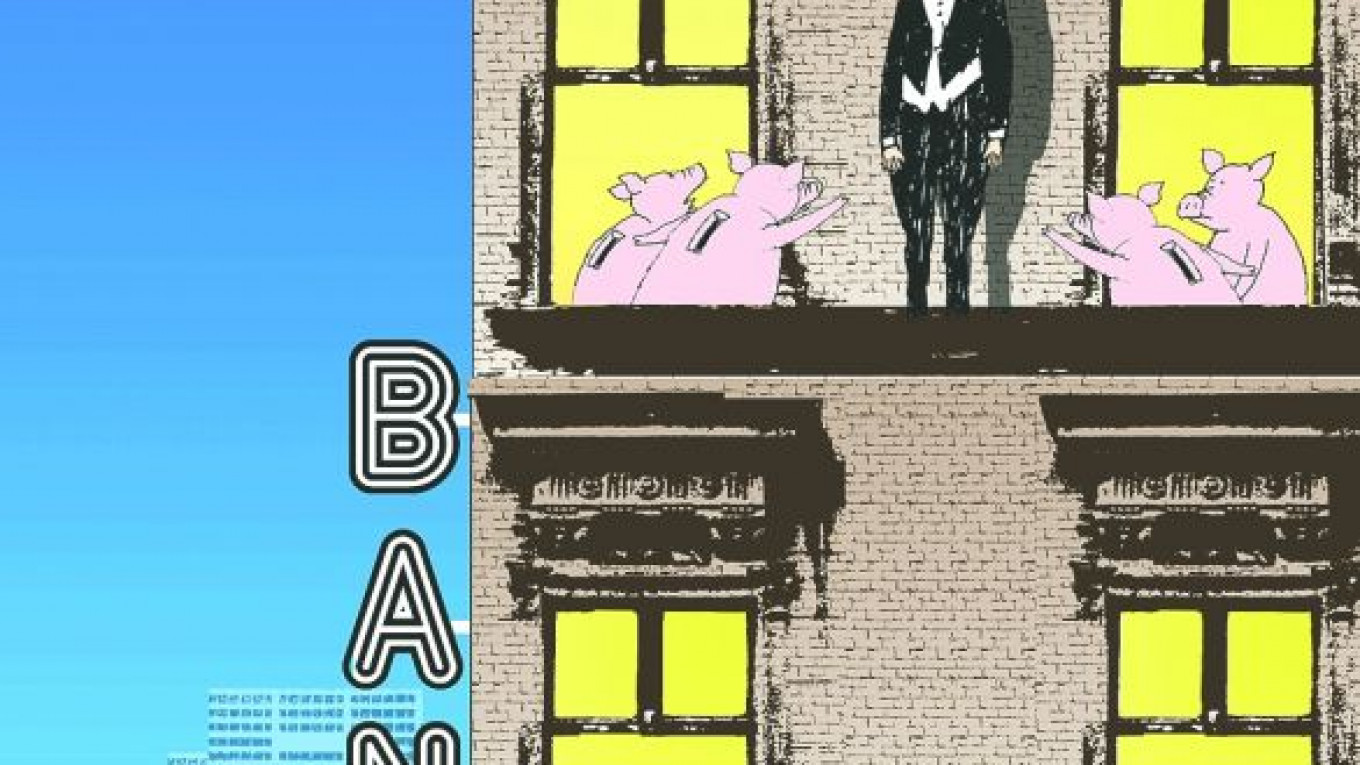

There is nothing new in this, of course. The enduring image of the 1929 stock market crash is of bankers lining up to jump from a skyscraper window. Humorists such as Will Rogers based much of their repertoire on the hapless bankers from that era. When I worked in Bangkok during the 1997 to 1998 Asian financial crisis, high-rise suicide was a frequent occurrence in the region.

But beyond the cartoons and satire, there is a real problem in the finance industry that is being ignored and that all too often results in early morning tragedies on commuter rail lines. The people who run the finance industry are not too interested because there is no place, or sympathy, for failure in an industry built to reward winners. There is little sympathy from people outside of the industry because of the resentment factor that has been built by the perception of players' greed and feckless behavior, even though that behavior involves relatively few but very loud people.

The vast majority of people working in the global finance industry are ordinary, hard-working, normal people. Well, normal in the sense that they get withdrawal symptoms if separated from their Blackberrys for more than a few minutes. Normal also in the fact that the industry has one of the highest incidences of divorce, physical burnout and an above-average rate of suicide.

Several studies published in the British Medical Journal and similar resources conclude that a large number of bankers and traders feel compelled to live in the style expected of winners in the industry, usually based on false images depicted in movies or, simply, popular perception. Many also confuse real money — their actual income — with the vast sums that they deal with or write about on a daily basis. Very quickly you can get sucked into the bonus culture where it is acceptable to live beyond your means for most of the year because "the bonus will cover it."

But then the bonus will not cover it if markets have been bad. Or, worse, you lose your job and have no hope of securing a new position capable of covering your perceived worth and actual liabilities.

Gamblers Anonymous says it gets many former finance industry people who thought they could simply substitute lost earnings by "playing the market" with borrowed money or their own savings. Most regularly gambled in the spread-bet, foreign exchange or the futures markets, using sums disproportionate to their ability to pay. They had, after all, become accustomed to dealing in such large amounts in the day job. Among them, a lucky few end up at support groups such as Gamblers Anonymous. Others end up under trains or falling from high-rise building windows.

A total of 4,900 people above the normal trend committed suicide in major cities in the 12 months following the Lehman Brothers collapse and the onset of the global crisis, according to World Health Organization data published in September in the British Medical Journal. The journal specifically linked the increase in suicides to the financial markets crisis.

A similar trend was observed by the Internet search engine Google, which reported a sharp rise in the number of people searching for ways to commit suicide between the start of the crisis in September 2008 and the start of a market rally six months later.

It is, perhaps, no coincidence that the low point for the U.S. benchmark equity index, the S&P 500, in March 2009 was 666.

While there is a lot of human tragedy in the finance industry, there is also the other side of the coin: those who are addicted to wealth accumulation and winning. Happy are those who can keep their sanity and live a normal life or, even better, those who take the money in the good years and leave.

While suicide and a gambling addiction are tragedies we can understand and properly deserve our sympathy, the contention that wealth accumulation and winning is also an addiction will only bring a snigger and disbelief. It is nevertheless a real issue and many people in the finance industry endure 364 days of misery just for that one more payday. For them, life has long since ceased to be about the money. It is about winning and beating your peers.

This is what Adam Smith, a pseudonym, wrote in "The Money Game," first published in 1967. The book defined and continues to define our industry and the people who participate in it. The author contends that most big players are in it for the game and would happily continue to "play" for matchsticks if that was the way to keep score against their peers. Recently, an ex-Wall Street trader, Sam Polk, wrote an article in The New York Times describing the culture and addiction of "one more payday," how he struggled to get off the treadmill, and how he dealt with the withdrawal symptoms from no longer earning bonuses. He has now formed a charity called Groceryships to help struggling families.

Globally, the finance industry most often engenders ridicule, criticism, anger and sometimes envy. Sympathy is rare. It is not an industry that ever seeks sympathy or even understanding, even from those within the industry who regard wealth addicts as winners and suicide as collateral damage.

As Moscow now builds its own financial industry, you would like to think that the approach might be different. But of course it will not. "It's different this time" are often cited as the four most expensive words in the English language. "It won't happen to me" are the five most dangerous.

Chris Weafer is senior partner with Macro Advisory, a consultancy advising macro hedge funds and foreign companies looking at investment opportunities in Russia.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.