A quickly-passed State Duma bill and a seemingly casual remark from President Vladimir Putin at the end of a marathon news conference started an amnesty that set free several high-profile prisoners, including former Yukos CEO Mikhail Khodorkovsky, Pussy Riot's Maria Alyokhina and Nadezhda Tolokonnikova, and a "crew" of Greenpeace activists.

Roughly one month after many of the inmates were set free, The Moscow Times looks back at some of the experiences they have shared since then.

1. See Your Family

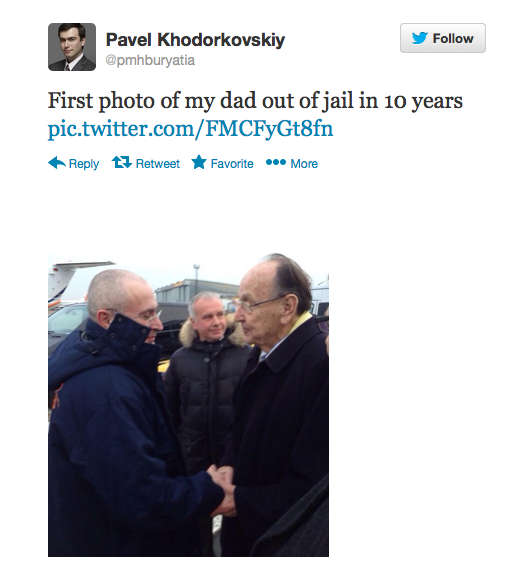

The No. 1 thing that the recently amnestied prisoners did after being released in late December was to go see their families and friends. After being freed Khodorkovsky, who was arrested in 2003 and convicted in two trials for embezzlement and tax evasion, made his way directly to Germany, where his mother is receiving medical treatment. The longtime inmate went to Berlin to meet with his parents, children, and, for the first time, his granddaughter.

Khodorkovsky’s son Pavel tweets a picture of his father with former German minister Hans-Dietrich Genscher.

Pussy Riot members Maria Alyokhina and Nadezhda Tolokonnikova, both mothers who were sentenced to two years on hooliganism charges, also reunited with their families and each other, sharing a plethora of pictures throughout the holidays.

Tolokonnikova tweeted about a ‘new Pussy Riot concert’ with Alyokhina (left) and her daughter Gera.

Tolokonnikova tweeted about a ‘new Pussy Riot concert’ with Alyokhina (left) and her daughter Gera.

Dutch activist Mannes Ubels is greeted by his girlfriend after leaving the detention center in St. Petersburg. (Greenpeace)

Tomasz Dziemianczuk after being released on bail from the detention center in St. Petersburg. (Greenpeace)

2. Share Your Story

Journalists from all over the world and their audiences wanted to hear from the newly released political prisoners. Pussy Riot chose opposition Moscow television station Dozhd and socialite-turned-journalist Ksenia Sobchak for their first exclusive televised interview before giving a wider news conference.

Alyokhina, Tolokonnikova and Sobchak before their interview.

Khodorkovsky also gave careful thought to where to hold his meeting with the press, ultimately choosing the Check Point Charlie.

Pavel Khodorkovsky tweets a panorama picture of his father’s Berlin press conference.

Pussy Riot has also taken to sharing their own news, becoming active on Twitter once again. Alyokhina created an account after her release and Tolokonnikova added an English-language account to her Russian one, which had seen little action since just before her arrest in February 2012, when she tweeted a picture showing a plumper, younger version of herself with a hamster.

A young Tolokonnikova with a hamster.

Her message after being released was more profound, saying, “I was thinking. Being freed, it's more cheerful."

In other cases readers have been reminded of the prisoners’ cases without them saying anything. Greenpeace and Russia popped back up in headlines together after the Russian Fisheries Agency said that the environmental organization was most likely .

3. Travel the World

The “Arctic 30” Greenpeace activists, who were detained for protesting at a Gazprom oil rig off of Russia’s northern coast, came from all over the world and returned to their homelands after being released. The international crew went home to places as close as Russia and as far flung as New Zealand and Argentina.

While some prisoners headed home, others took their freedom as an opportunity to travel more widely. Khodorkovsky did not stop in Germany and made trips to Switzerland to take his sons back to school for the new semester.

(khodorkovsky.com)

As well as to Israel to his former business partners.

Leonid Nevzlin sits in front of a picture of Khodorkovsky a news conference in Tel Aviv, Israel, 2005. (Vedomosti)

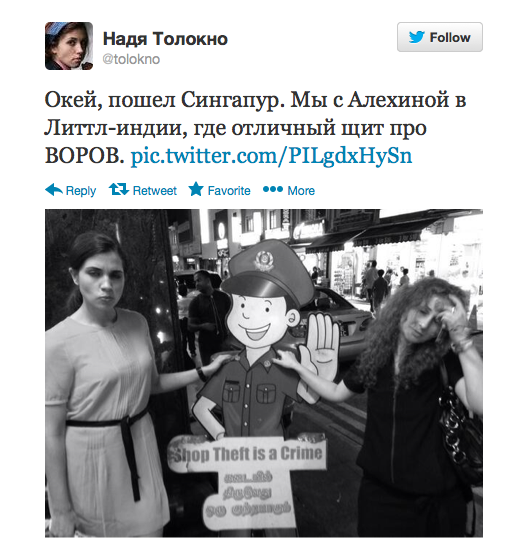

Pussy Riot may become as well-traveled as Khodorkovsky if they choose to get in on the awards circuit. Tolokonnikova and Alyokhina went to Singapore after being nominated for an art award for their “Punk Prayer” performance at Christ the Savior Cathedral in Moscow.

Tolokonnikova and Alyokhina take a stand against theft with a slightly stiff police officer in Singapore.

The pair also plan to travel to New York to speak at an Amnesty International concert in Brooklyn in support of prisoners’ rights.

4. Get Your Money Back

Getting out of prison and still believing in your own innocence can lead to problems for those organizations who probably wish you had stayed in jail. Since the release of Khodorkovsky, legal battles have intensified between former Yukos-affiliated companies and their buyers like Rosneft, which picked up many of Khodorkovsky’s bankrupt company’s assets in 2007. Rosneft faces more than $1.12 billion in debt claims and a U.S. federal court sided against the state-owned oil giant in a case earlier this month and told it to pay $186 million to a Yukos-linked company.

Though maybe not as savvy at business, the Greenpeace activists have also pushed to get their belongings and bail money back. Russian authorities have refunded part of the money that the environmentalists spent on bail before their eventual amnesty from hooliganism charges, as well as returning some of the protesters’ belongings.

Greenpeace is also working on the return of the Arctic Sunrise ship, which has been held by the Russian authorities since it was seized in September.

5. Remember Those You Left Behind

While a handful of prisoners, like those mentioned here, have gotten the vast majority of the press, the amnesty also extended to many others, and it is estimated that it affected up to 25,000 people, though many never served time. Still important to those who did go to prison, however, are those that are still in penal colonies throughout Russia.

Khodorkovsky maintains his innocence and closely followed Thursday's news of the Supreme Court's ruling on his business partner Platon Lebedev.

Khodorkovsky tweets about the news that his business partner Lebedev will be released from jail after his sentence was reduced to time served.

Pussy Riot has gone further, saying they will start a human rights organization. Tolokonnikova’s hunger strike before her release perhaps foreshadowed her and Alyokhina’s plans to fight for prisoners’ rights both in Russia and internationally at events like the Amnesty International concert.

The pair have been particularly active in Moscow, where they have attended hearings for the "Bolotnaya case" defendants, four of whom were amnestied but many of whom are still being tried for participation in “riots” at a May 2012 opposition protest.

While taking a snap of Tolokonnikova and Alyokhina in Moscow, photographer Denis Sinyakov, the same Denis Sinyakov who was among the "Arctic 30," remarks that the street decorations look similar to a fence around a prison's exercise yard.

The releases of those like Lebedev and other prisoners allegedly prosecuted for political reasons like rural teacher Ilya Farber, seem to show that the amnesty was part of a far broader-reaching strategy than an act simply designed to mark the 20th anniversary of the Constitution. Some analysts say that the releases signal the end of an era, though those released will mostly likely never forget their years behind bars.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.