Looking back at the main events that shaped Russia over the past 12 months, it is clear that 2013 will go down in history as President Vladimir Putin's "anti-year."

It was in 2013 that the powers that be not only embraced anti-smoking and anti-alcohol policies, but they also showed that they are anti-gay, anti-children, anti-chocolate and even anti-Halloween.

Perhaps new efforts by Putin to spread anti-American sentiment was predictable, but his decision to portray Russia as anti-Big Brother by granting asylum to U.S. intelligence leaker Edward Snowden took many by surprise — including Putin himself, who told reporters in Finland in late June that Russia was "completely surprised" by Snowden's trip to Moscow. How, then, does Putin explain reports that Snowden spent several days in the Russian consulate in Hong Kong just before he flew to Moscow?

Furthermore, Putin's credentials in a nationwide anti-corruption drive took a hit last week when he pardoned former Yukos chief Mikhail Khodorkovsky. His arrest in 2003 and 10-year combined jail terms have been widely interpreted as the Kremlin's punishment for the businessman's political ambitions aimed at Putin.

As it turns out, you can be as corrupt as you want if you are a friend of Putin, but if you are his enemy you get the "a-thief-must-sit-in-jail" treatment — at least until Putin needs to improve his image before the Sochi Olympics. In any event, Putin's selectively ruthless legal assault on Khodorkovsky brought new meaning to the expression attributed to Spanish dictator Francisco Franco: "My friends get everything, while my enemies get the law."

Here's a look at the top five political events of 2013 and how they shaped Russia.

1. The year of the ban.

Russia set a record for the number of bans this year. A ban on smoking in public places, enacted in June, was long-needed. But few actually believe that this law will make it any easier for nonsmokers to breathe as they walk down a crowded street or sit on a park bench. After all, smokers make up 40 percent of the population, and finding creative ways to skirt the law is a centuries-old Russian tradition, many would argue - particularly when it involves a highly addictive habit.

Nonetheless, there is still hope that a ban on heavy-duty trucks entering the Moscow Ring Road from 6 a.m. to 10 p.m., enacted in April, will help clear the air a bit. And to help clear the streets of intoxicated pedestrians and drivers, Russia enacted another ban: on alcohol sales in stores and kiosks after 11 p.m.

Chief sanitary inspector Gennady Onishchenko also had a record year for bans.

First, he banned chocolate imports from the Ukrainian company Roshen in July and Moldovan wine in September. The real reason, of course, had nothing to do with sanitation and everything to do with bullying Kiev and Chisinau into walking away from partnership agreements with the European Union.

Then in early October, he banned Lithuanian dairy products. The measure was to punish Vilnius, the host of the EU summit in late November, for pushing Ukraine, Moldova, Georgia and Armenia to sign the partnership agreements.

In late October, Onishchenko himself was "banned" when Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev did not renew his contract as head of the agency, purportedly because of his excessive banning zeal.

Also this year, Liberal Democratic Party head Vladimir Zhirinovsky tried to ban foreign words, while one of the party's deputies, Mikhail Degtyaryov, tried to ban the U.S. dollar. But not all was lost in this category of absurd bans: The Omsk region succeeded in banning Halloween celebrations in local public schools.

2. Anti-American campaign against U.S. adoptions.

This ban deserves its own listing. The adoption ban, which the Kremlin said was needed to protect Russian children from "abusive U.S. parents," was imposed shortly after U.S. President Barack Obama signed the Magnitsky Act, which punishes Russian officials implicated in human rights violations. But instead of a tit-for-tat — for example, the U.S. imposing sanctions on 18 Russian officials with Russia responding by targeting 18 U.S. officials — Russia adopted a blatantly asymmetric measure that punished thousands of U.S. parents who had never committed a crime against children. These parents badly wanted to adopt Russian children, who badly wanted to escape the grim, often abusive, life in Russian orphanages.

In reality, less than 0.2 percent of U.S. parents who have adopted Russian children over the past 20 years were charged with child abuse. What's more, contrary to what the Kremlin's propaganda machine has claimed, the overwhelming majority of parents who were found guilty of child abuse received significant jail terms. The other 60,000 or so law-abiding U.S. parents provided loving, caring homes to Russian children, including many with disabilities.

Russia's flat ban on U.S. adoptions deserves the "Most Cynical Political Revenge Award" of the year. The Kremlin had two main political goals in passing the ban. One was to incite anti-Americanism among President Vladimir Putin's core electorate by trying to characterize the majority of U.S. parents as pedophiles, psychopaths and sadistic child abusers.

Second, by presenting the U.S. adoption ban as "protecting the rights of Russian children," the Kremlin tried to deflect attention away from the fact that the only thing it was really protecting was the group of 60 government officials linked to the 2009 prison death of anti-corruption lawyer Sergei Magnitsky and the related $240 million embezzlement scheme that Magnitsky exposed. Incidentally, not one of those 60 suspects has been tried in court.

Thus, for the sake of a cover-up and scoring cheap political points as part of its broader anti-American campaign, the Kremlin was willing to sacrifice the lives of thousands of Russian orphans.

3. Edward Snowden.

The Kremlin thought it scored a major victory by giving Snowden temporary asylum on Aug. 1. It endlessly praised Snowden as a "U.S. dissident" and "hero of democracy," while also painting itself as a supporter of privacy rights. But the absurdity and hypocrisy of the Kremlin's stance was clear to nearly everyone, including Putin's most ardent supporters, who know that the Federal Security Service is one of the worst global violators of citizens' privacy rights.

Almost as if to underscore the Kremlin's own hypocrisy, in late October the Communications and Press Ministry released a government order that will allow the FSB direct access to the content of Russians' telephone calls, e-mails, instant messages and other Internet communications without a court order. Internet providers will be forced to install equipment on their servers that will provide a direct link to the FSB.

Snowden, meanwhile, received the Sam Adams Award on Oct. 10 for his "integrity in intelligence" at an undisclosed location near Moscow, and he has accepted a website job at an undisclosed Russian company.

In December, he announced his mission as a whistleblower was accomplished, despite conveniently ignoring Russia's surveillance abuses.

Putin put a nice cap on the Snowden affair by saying at his expanded annual news conference on Dec. 19 that he is envious of Barack Obama for being able to spy on anyone he wants and getting away with it. Kudos to Putin at least for his honest admission on this count.

Snowden, however, wasn't the only whistleblower to make news in Russia in 2013. The country's own top whistleblower, Alexei Navalny, was found guilty of embezzlement and given a suspended five-year sentence this summer in a politically driven trial. He then got his a revenge of sorts in September, winning an impressive 27 percent of the vote in the Moscow mayoral race. Russia's other most prominent whistleblower, the late Sergei Magnitsky, was found guilty of tax evasion in July in an outrageous and shameful posthumous trial that made even Josef Stalin's show trials look tame in comparison.

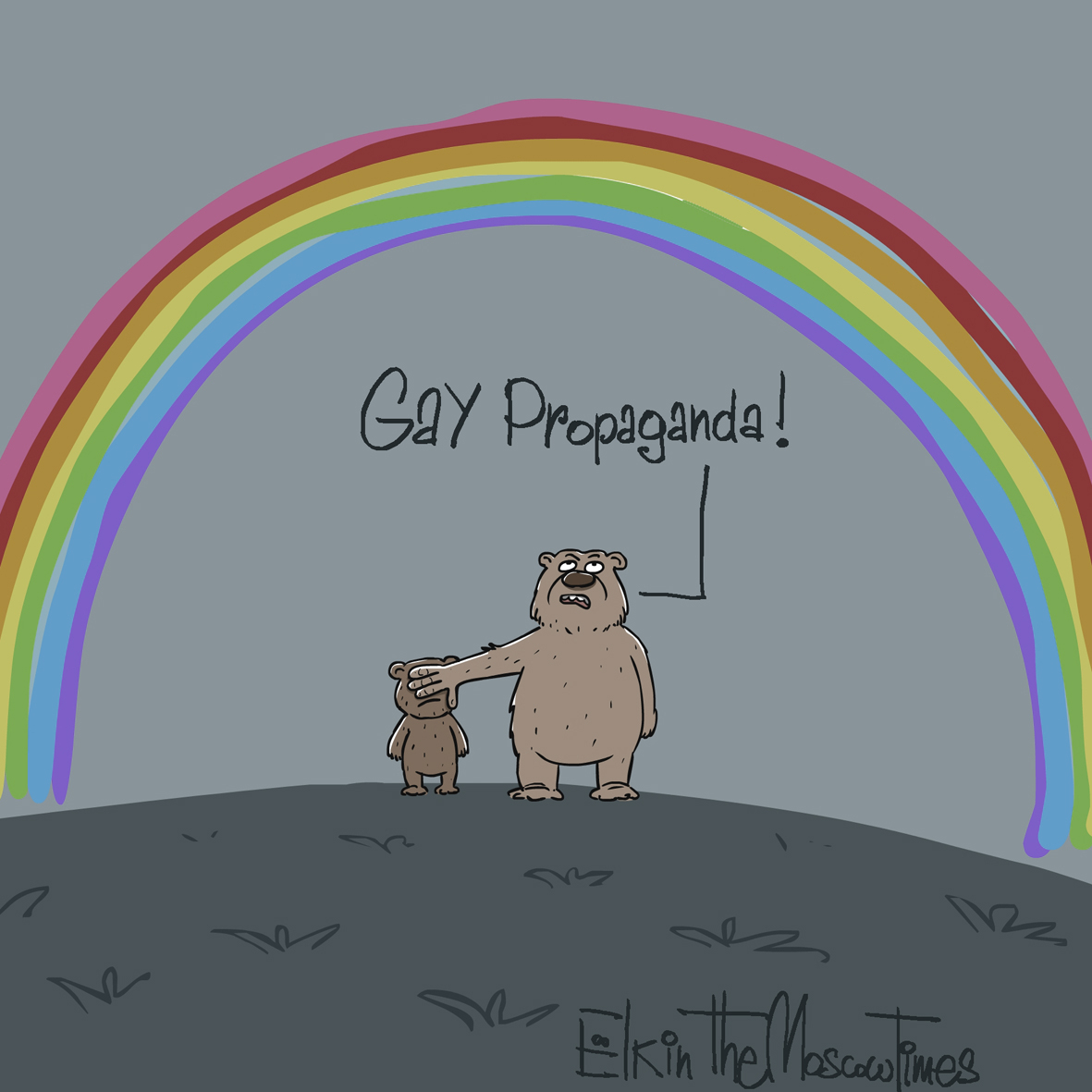

4. The state-sponsored anti-gay campaign.

The Kremlin's propaganda machine went out in full force this year to convince Russians that the greatest threat to Russia — along with the U.S. and NATO — are homosexuals.

Leading the homophobia campaign throughout the year were Dmitry Kiselyov and Arkady Mamontov, news and talk show hosts on Rossia 1 state television, and a series of pseudo-documentaries on other state-controlled television stations. They all told viewers that homosexuality in Russia was a Western conspiracy meant to corrupt the country's fundamental moral and spiritual values, exacerbate its demographic crisis and spread HIV among Russians.

The State Duma joined the anti-gay campaign, passing the controversial "gay propaganda law" unanimously in June. The law, which essentially codifies Russia's homosexuals and lesbians as second-class citizens, states that anyone who expresses a "distorted understanding of the social equality of traditional and nontraditional sexual relations" in the presence of a minor is subject to a fine of 5,000 rubles ($150). At least three Russians have already been fined under the law.

The irony is that if anyone has a "distorted understanding" of homosexuality, it is the Duma deputies. The Liberal Democratic Party took this ignorance one step further, introducing a bill that would use state funds to "treat" homosexuals of their "illness" with the goal of turning them into heterosexuals.

The other irony is that while the new law is presented as a defense against gay propaganda, the real propagandizers are the government and Russian Orthodox Church, which are trying to impose their "spiritual, traditional and moral values" on those who have "nontraditional" values.

5. Mikhail Khodorkovsky's pardon.

It would seem that Putin wanted the pardon as much as Khodorkovsky as it gave Putin a nice opportunity to appear merciful. At the same time, however, many of Putin's critics have rightly asked: Who was behind the politically driven case to put Khodorkovsky in jail in the first place 10 years ago? And why did Putin wait until seven months before Khodorkovsky's scheduled release in August 2014 to show mercy?

With the pardon, Putin might hope to share some of the glory as the "kind tsar" in advance of the Winter Olympics and the Group of Eight summit, both in Sochi next year. Had Khodorkovsky served his full sentence, he would have been the only hero in this drama. Now, Putin hopes to get some of the global spotlight for his "humanitarian gesture."

Despite Kremlin efforts to spin the pardon as a sign of Putin's strength, Putin is still very concerned about Khodorkovsky's influence and moral authority as a free man. That is why Khodorkovsky was whisked away and placed on a private jet to Germany within hours after he was released from prison - a scene taken right out of a Cold War spy thriller.

That is also why Khodorkovsky must effectively remain abroad in exile forever. If he returns to Russia, he will likely be forced to pay a $550 million fine — reportedly more than his current net worth — that dates back to his first conviction in 2005, or face another criminal trial. In addition, he must refrain from engaging in Russian politics and from seeking legal claims to former Yukos assets that were essentially nationalized by state-controlled Rosneft in 2004.

Rosneft CEO Igor Sechin, a close Putin ally who is considered the mastermind behind the state takeover of Yukos, will never give Khodorkovsky his $40 billion company back, of course. But he did offer him a mid-level job at Rosneft — and "only if his background meets the qualification requirements for the position," as he put it. This malicious sarcasm was matched only by presidential spokesman Dmitry Peskov, who, in answering a question from an Interfax reporter, smugly concluded that Khodorkovsky's pardon request meant that he finally admitted his guilt, which was a blatant lie.

But these snide remarks just days before New Year's should not ruin the holiday spirit for any of us. Amid all of the anti-news throughout 2013, the fact that Khodorkovsky is now free is certainly the best news we have heard all year.

Michael Bohm is opinion page editor of The Moscow Times.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.