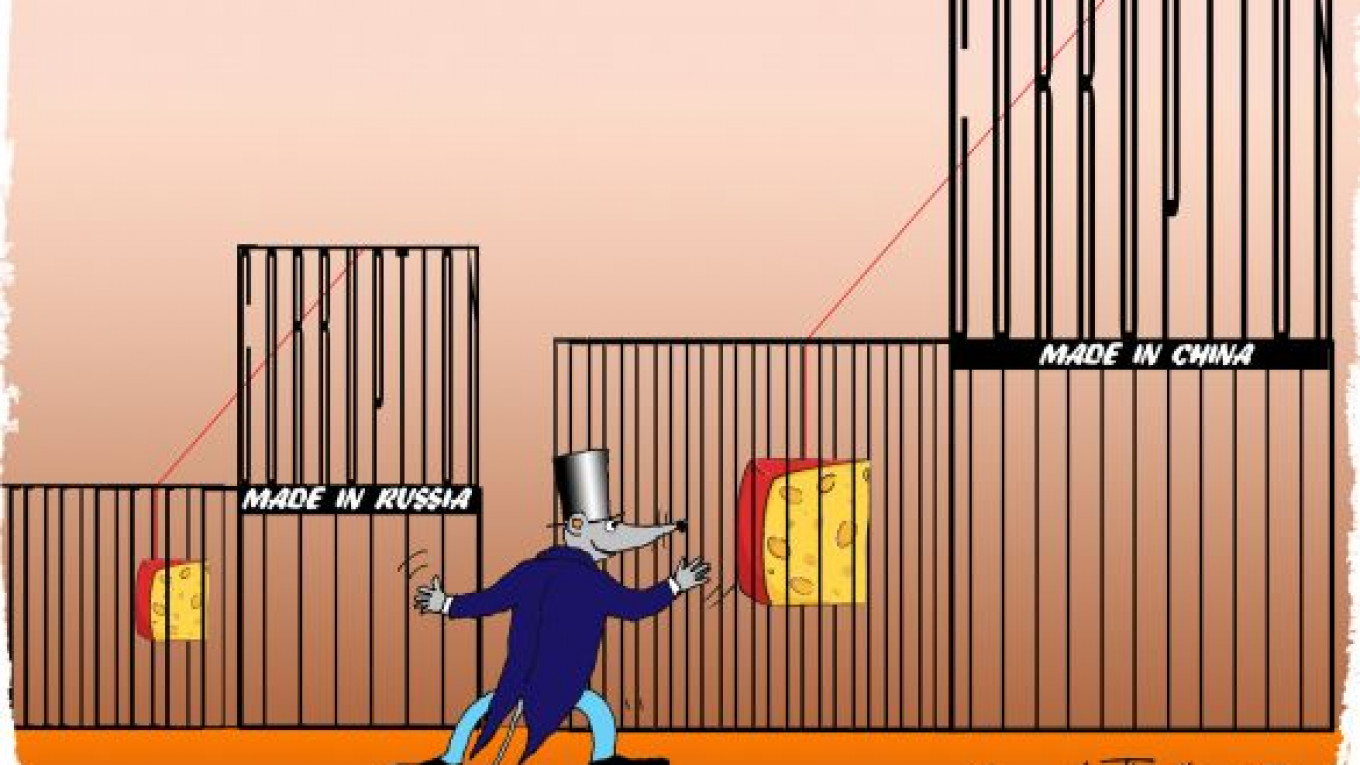

Russia and China are both two large, emerging markets. Both have growing middle classes topped with a frothy layer of the super-rich, and both have thorny, challenging business environments that are fraught with corruption. So why do investors leap at the chance to get into China and balk at Russia?

What a difference a billion customers makes.

How mesmerizing to think of selling something to a billion people. Who could say no to an opportunity like that? In reality, few do, despite the considerable challenge corruption poses in China.

If you dismiss Russia only because it small size relative to China fails to justify the never-ending battle with corruption, you will miss a key market. If you rush into China because its enormity dwarfs any concerns about corruption, you risk crashing on the China superhighway.

But when talk turns to Russia, with only 143 million customers, the conversation grows difficult. For some reason, investors find Russian corruption harder to metabolize. It is puzzling. The problem is as corrosive in one country as in the other.

This divergent approach to investing in Russia and China puts investors in both countries at a disadvantage. If you dismiss Russia only because its small size relative to China fails to justify the never-ending battle with corruption, you will miss a key market. If you rush into China because its enormity dwarfs any concerns about corruption, you risk crashing on the China superhighway.

It is not just a question of market size. The split stance on doing business in Russia and China echoes the equally split public dialogue on the two countries. Russia gets far harsher treatment than China for the role corruption plays in its economic and political systems. Everyone keeps complaining that corruption seems to be part of Russian culture. In the West, this kind of talk verges on reflex, rooted in decades of anti-Soviet invective that finds its modern incarnation in Russia-bashing.

That criticism is applied unevenly. Though China was the power-behind-the-throne during the Korean war, the West seems to have forgotten that and re-engaged with China in the early 1970s through ping-pong diplomacy and eventually full recognition over the Taiwan upstart. Although a Communist system, China never grabbed the West’s attention as the “evil empire” as the Soviet Union once did and as Russia still does to a large extent.

This does not mean that every investor rushes headlong into corrupt transactions in China without considering the implications. On the contrary, many international companies doing business in China prepare exhaustive anti-bribery and corruption policies to protect themselves from taint and regulatory zeal in their home jurisdictions. The U.S. Justice Department looks at China as prime hunting ground to catch companies breaking Foreign Corrupt Practices Act statutes.

Of the companies that actually adopt comprehensive anti-bribery and corruption policies, few will do much to bring them to life. Their policies remain on paper. Some launch a flashy e-learning tool that sits near the bottom of in-boxes in their Chinese subsidiary. Others will at best make a few token anti-corruption gestures — a company-wide e-mail from the CEO perhaps — and see how it goes. This remains a problem in Russia, too.

The anti-corruption environment in China is taking on new energy with the cases around pharmaceutical companies and Chinese health care, a system widely known to be corrupt to its very core. This is where the billion-customer motivation runs most true. Not everyone wants a car or the latest electronic gadget, but everyone at some point in his life will need health care. Multinational companies that are directly or indirectly related to the health care sector are drooling at the prospect of more than a billion patients.

In the world of compliance, we talk about “adequate measures” that a company takes to protect itself against corruption. But the recent probes into health care companies in China are forcing companies to redefine the meaning of “adequate.” For example, one adequate measure is due diligence: doing background checks on suppliers, distributors and other third parties with whom you will do business. The same is the case in Russia. Whether you’re doing business in central Moscow or the provinces, you need to know as much as possible about your partner and the potential risks that a company presents to you.

In most environments, a quick look at a business database and a credit check are sufficient. But in China, where neither databases nor credit checks are possible, “adequate” due diligence means sending people out to discreetly talk to the partner’s customers, vendors, regulators and former employees to get a deep sense of who the company is and how they do business. Russia presents a strong parallel here, as well. Quick database or credit checks are either hard to come by or fail to present a complete picture.

Many of the problems with health care companies in China today are a result of not doing adequate due diligence. Who cares if there are a billion Chinese customers if you’re going to destroy your company and your reputation in trying to reach them?

So Russia may not have a billion potential customers. It may also be a popular whipping boy for its business behavior. But companies who avoid Russia because of corruption and rush into China because of its market size are missing the point. Both countries contain the same risks, and each harbors significant reward.

Charles Hecker is a former head of Control Risks’ Moscow office. Kent Kedl is managing director, Greater China and Northern Asia, at Control Risks and a long-term resident of China.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.