Only one month ago, it seemed that Russia had lost the competition with the European Union over Ukraine. But on the eve of the summit in Vilnius last week, it seemed that President Vladimir Putin had done the impossible. Not only did he upset the agreement between Ukraine and the EU, but he also convinced the Ukrainian leadership to reconsider restoring and strengthening economic cooperation with Russia.

In reality, Russia and the EU have no urgent reason to come to Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych's aid, considering the way he has played both against the other in an attempt to win the best possible terms for himself. Brussels would probably prefer cutting its loses with Yanukovych and hope that another, more Western-leaning president will be elected to office in 2015.

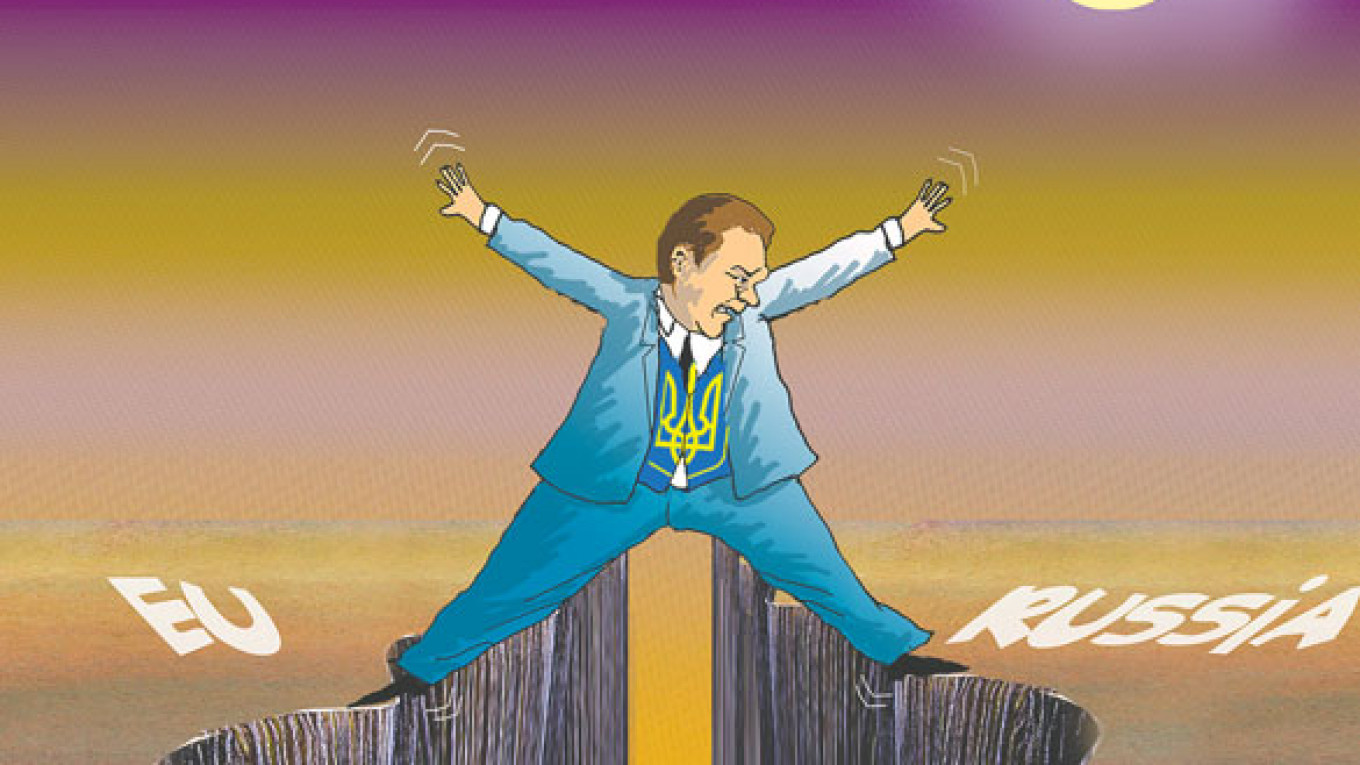

Yanukovych is engaged in a risky game, attempting to balance the pro-European sentiment in western Ukraine with the pro-Russian mood in the east.

Yanukovych is engaged in a desperate game, attempting to balance the pro-European sentiment in western Ukraine with the pro-Russian mood in eastern Ukraine. Yanukovych says the country is on a strategic course toward European integration and complained openly to Europe that it is difficult dealing with Putin single-handedly. Of course, such words do not endear him to Moscow, but Yanukovych is no sentimentalist. He must find some way to hold onto power until the presidential election in 2015, although he has only a slim chance of re-election. His popularity rating has slipped just below that of opposition leader and future presidential rival Vitali Klitschko. Therefore, the Yanukovych administration is planning to submit a bill to parliament that would prohibit Klitschko from running for president on the grounds that he lived too long outside the country, in Germany. Former Ukrainian Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko poses an equally potent political threat, and that is why Yanukovych prefers keeping her behind bars.

Yanukovych underestimated the potential for political protest when he abruptly reneged on his commitment to sign the Association Agreement with the EU. He raised the stakes in this dangerous game even higher when, on Saturday night he dispatched riot police to disperse mass demonstrations in Kiev. The danger is that at some point some members of the elite might oppose using violence against citizens who are peacefully protesting. In protest against the use of force to dispel demonstrators, presidential administration head Sergei Levochkin has already submitted his resignation, and several retired Ukrainian generals have submitted a letter of protest. There are also splits within Yanukovych's Party of Regions that could leave him without a majority in parliament. It would come as no surprise if siloviki in western Ukraine already begin defecting in the coming days.

Apparently, Yanukovych hopes he will be able to negotiate more favorable terms with the EU, sign the Association Agreement and trumpet that achievement to voters before the presidential elections in 2015. While in Vilnius, Yanukovych demanded visa-free travel between the EU and Ukraine, $15 billion in low-interest loans from the International Monetary Fund, $7 billion from Brussels to modernize Ukraine's gas transport system and 160 billion euros ($217 billion) to adapt Ukrainian economic norms to European standards. That is roughly the amount Brussels spent integrating Poland into the EU. But Brussels was not offering Kiev full EU membership, only the creation of a free trade zone and an expanded market for European goods through Ukraine, changes that would have displaced Russia from that market to some degree. Countries already holding free trade agreements with the EU include Jordan, Tunisia, South Africa, Algeria, Morocco, Chile and Mexico. Ukraine was to have been just one more country on that list and nothing more.

Putin scored a public relations victory by foiling the EU bid for Ukraine, but at the same time, Moscow finds itself in a trap. The likelihood that Russia could lose Ukraine is perhaps even greater now than it was one month ago, particularly if integration with Russia does not improve Ukraine's economy or the people's low standard of living.

Putin recently reminded Ukraine that it holds almost $30 billion in outstanding loans from Russian state banks. Talks about easing the terms on those loans could also serve as an argument in favor of a rapprochement with Russia. Perhaps the two countries could also address conditions by which Russia supplies gas to Ukraine. Yanukovych believes that calculations for a fair price should proceed from the average European price of $370 less the transit fee of $70. However, Moscow currently sells gas to Kiev according to the contract signed by Tymoshenko. That price is $510, less the set limit of gas sold at a discounted price and pumped into underground storage facilities.

But the implementation of these projects largely depends on the answer to the main question: Is Yanukovych cynically deceiving Moscow, leveraging Russia's offer to later sign an association agreement with the EU, only this time on better terms? And with the unrest in Ukraine increasing daily, does Yanukovych even have a political future anyway?

Georgy Bovt is a political analyst.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.