The public sometimes pays little attention to events of major importance. One such example was a recent meeting on military education at the Ryazan Airborne Forces School that both President Vladimir Putin and Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu attended. That gathering marked the beginning of the end for the military reforms implemented by Shoigu's predecessor, former Defense Minister Anatoly Serdyukov. At that meeting, both Putin and Shoigu made a number of statements to the effect that future officers must receive the training and skills necessary for modern warfare. That is true enough, but Russian leaders have been saying the same thing for the past 100 years even while training their soldiers not for the next war, but for the last one.

Yet we could overlook even those vacuous statements were it not for one consideration. Putin said the military education system should be "optimized" as early as 2014 and that it is necessary to preserve a number of military academies as independent educational institutions. These include the Mikhailovsky Artillery Academy, the Tactical Air Defense Academy, the Aerospace Defense Academy and the Radiation, Chemical and Biological Defense Academy. But Shoigu went even further. Pointing out that the military education system currently consists of 18 academies and 15 branch institutions, Shoigu proposed that Russia "once again give the branch organizations the status of independent educational institutions and recreate the system of military academies, universities and training schools that had previously developed over Russia's history."

But it is these very proposals that spell the end of the reforms to military education that had been in place for the last four years. Now, the top military brass and the defense minister conveniently ignore all of the work accomplished, and the fact that Putin himself, referring to the success of those reforms, wrote that "10 major scientific and educational centers will be established in a rigid hierarchy, making it possible for officers, at whatever point in their service, to continually advance to the next level."

The reformers had faced two problems. First, not only the quality of education, but also the enrollment in the country's provincial military schools had dropped significantly, leaving 700 to 800 faculty and staff for every 200 students. Second, as the system was then structured, officers typically spent about half of their 25-year military career in educational institutions: five years at a training school, three years in the Armed Forces Academy and two years in the General Staff Academy.

The Serdyukov reformers proposed consolidating all of these smaller schools into larger scientific and educational centers grouped according the various branches of military service. Of course, Shoigu is correct in pointing out the difficulty of managing branch institutions that are often located thousands of kilometers from the main campus. But the branch institutions were originally seen as a transitional measure that would soon be closed down after fulfilling their function. The reforms also proposed shutting down specialized academies and cutting the curriculum at the General Staff Academy from two years to several months. The plan called for future lieutenants to first receive basic military training and then, upon becoming an officer, begin serving and continuing their education along the way. Officers would have been able to earn promotions in rank by completing courses of reasonable length and learning new skills and knowledge in specific areas. Lastly, and most important, the reformers planned to radically revise the curriculum. The future officers would have focused on the fundamentals, not on specialized branches of knowledge. They would have learned how to learn — that is, how to master the rapidly changing technologies needed to win future wars.

Now the Defense Ministry has done an about-face and called for reinstating the status of the training school branches. But does anyone seriously believe all 33 military educational institutions flung across Russia's immense territory will be able to provide the high level of education the top brass is demanding? What's more, plans call for once again making schools answerable to the high commands in each branch of service. The problem is that senior commanders will require cadets to specialize in specific weapons systems that could quickly become obsolete once the next generation of equipment is introduced. Driving the final nail in the coffin, Shoigu proposes abandoning the main idea of the reforms — that of consolidating and simplifying the various military educational institutions. Instead, he proposes turning back the clock to the Soviet system of military education with its training schools, specialized academies and General Staff Academy.

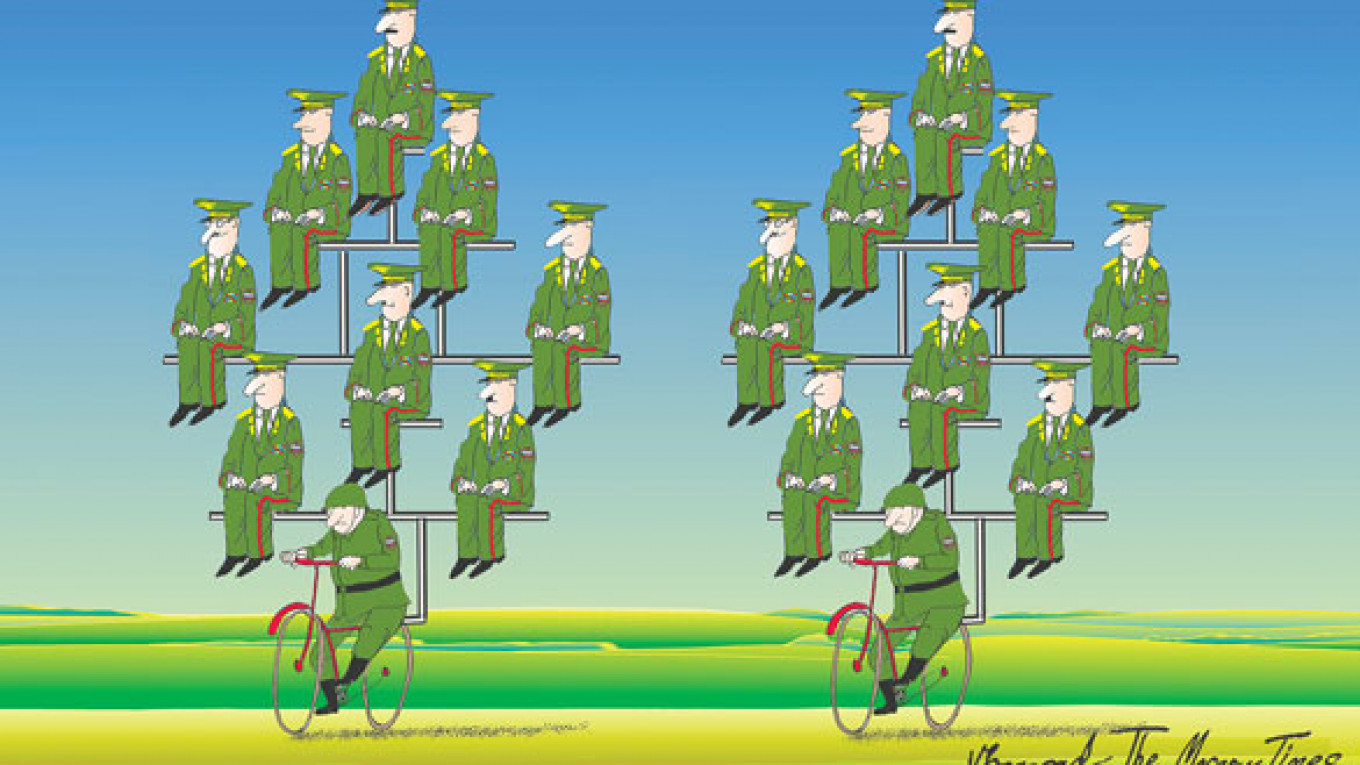

Serdyukov's military reforms are essentially dead now. Unfortunately, the problems do not end there. The decision to return to the old system will once again result in the "mass production" of military officers. To justify their existence, each institution will now lobby — with the help of prominent graduates only too happy to promote their alma mater — in a drive to enroll as many new cadets as possible.

That will clearly result in a glut of officers. What's more, before year's end the Defense Ministry will grant officer status to graduates of the 2010-12 class who had the position of sergeant and also extent officers' term of service by five years. Of course, senior officers such as majors and lieutenant colonels will take advantage of that opportunity, a change that will result in an additional 26,000 people in the officer corps according to Viktor Goremykin, head of the Defense Ministry's main personnel directorate.

Notably, this was the very problem that motivated Serdyukov to introduce reforms in the first place. He pointed out that there were about as many colonels as lieutenants. Even they were outnumbered by majors and lieutenant colonels, with the result that one officer was overseeing every two enlisted men. That is why he set out to ruthlessly cut the ranks of the officer corps. But the revived mass production of officers also means a return to the idea of a mass-mobilization army. After all, to justify their high numbers, a bloated officer corps will need greater numbers of soldiers to command. That means only one thing: Russia is doomed to return to the same militaristic model that Serdyukov had tried to phase out.

Alexander Golts is deputy editor of the online newspaper Yezhednevny Zhurnal.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.