A group of young ballerinas from the Moscow State Academy of Choreography, better known as the Bolshoi Ballet Academy, stand in a practice room and stretch, preparing to be inspected.

A female instructor helping to select dancers for the academy's 240th-anniversary celebration, a show that will feature big-name stars as well as ballet students from the academy and around the world, enters the room. She looks the girls over from their hair buns to their slippered feet, staring to determine whether each one is too heavy, too skinny, or has just the right look.

The instructor stops in front of one ballerina, Precious Adams, an 18-year-old American from Detroit. "What are you doing here?" the instructor asks curtly, then tells her to leave the audition room.

Though plenty slender, Adams does not have the same look as the other ballerinas at the Bolshoi Academy, a ballet school affiliated with the iconic Bolshoi Theater. Unlike almost all her classmates, she is black, and in the spring she will become one of the first African-American ballerinas to finish the school, despite facing persistent discrimination at an institution used to dancers of a paler complexion.

In her more than two years at the academy, Adams has been left out of performances because of the color of her skin, she says, and has been told to "try and rub the black off" to make herself look more like what directors want for shows like the school's 240th-anniversary performance earlier this month.

"Some of the teachers know in the back of their minds that it is unfair, because they know that I can do what these other people are doing just as good if not better than them," Adams said in an interview. "Teachers have tried to vouch for me before, but if the almighty voice says it's not right — it doesn't look right — then whatever they say goes."

Adams grew up far from the high-pressure world of the Bolshoi, in a middle-class town outside Detroit, Michigan, called Canton, but she began her rise toward the upper echelons of classical ballet early in life.

She began ballet lessons at age five, and at nine she joined a nearby studio led by Sergei Rayevsky, a graduate of the Vaganova Academy of Russian Ballet in St. Petersburg. She then moved farther and farther away from home in order to develop her talent, studying in Toronto, New York City and Monaco, before applying to the Bolshoi after winning a scholarship to study Russian and ballet at the school's stateside summer intensive program.

Her Russian studies were complemented by a rapid immersion in the language when she was accepted to the Bolshoi Academy in Moscow and moved into the school's dormitories near Frunzenskaya metro station in 2011, when she was just 16.

The school has become increasingly open to foreign students, including about 20 Americans, who are helping to bankroll the academy's renovations by paying yearly tuition of 680,000 rubles (about $21,000). Fittingly for a school that is becoming more international, with one-third of each 36-person class coming from abroad, technique classes are a smattering of French moves like pirouette and Russian commands like вперед! (Forward!).

But unlike the rest of her class, which includes other international dancers of various complexions and a biracial American woman, Adams said her dark skin has singled her out and prevented her from being cast in roles, particularly in group pieces.

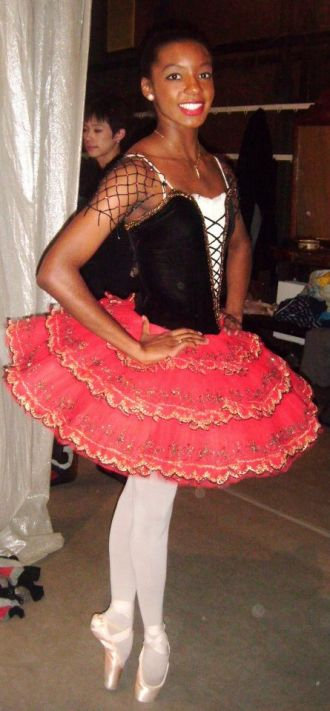

Adams performing a dance maneuver. She says she has been passed over for roles because of her skin tone.

She said that she tries not to let comments affect her — like one teacher's sincere suggestion that she experiment with skin bleaching — and continues to work hard on her craft. She was also aware of the pervasive racism in Russia prior to applying to the Bolshoi Academy.

"I knew before I came, everyone said, 'Be aware, you're going to be one of the only black ones. There's racial problems, be smart — don't take stuff personally,'" she said.

The most visible evidence of racism in Russia is often at soccer matches, where Russian fans — whose ranks often overlap with nationalist groups — yell slurs at black players on opposing squads.

Adams said she has grown accustomed to the casual racism of Russian society. She does not go out alone at night, she has gotten used to the stares from passersby, and her headphones silence remarks from people on the metro.

But at the Bolshoi, which seems worlds away from rowdy soccer bleachers, issues of discrimination may be affecting how her potential develops into a career. Performance time, in her words, "directly relates to you getting a job. If I can say I've only performed on stage four times out of the past three years, it doesn't look good."

"If I'd gone anywhere else, I'd probably have a lot more experience," she said.

Responding to Adams' allegations of mistreatment, the Bolshoi Academy said in a statement that they had received no report of discrimination from her and that school officials had not heard complaints from other international students, who hail from ten countries in the Americas, Europe and Asia. The academy also noted that all students get to participate in onstage practice and that Adams had received high marks for her time on stage.

Adams said that she did not make an official complaint because she was unsure if it would do any good, saying: "I don't think there would have been much of a response." She also said that in the heat of a competitive environment, she did not want "to look like I'm weak or that I feel sorry for myself."

Mario Labrador, a fellow American who graduated from the academy last year and is now a soloist at the Mikhailovsky Theater in St. Petersburg, performed for international audiences while at the academy and was taken with the Bolshoi Ballet on month-long tours of Greece and Italy. He said the ballet world and casting process is full of politics, including the perception that "you can't have a black dancer on stage because it changes the look, the scenery, the costumes" that were chosen to create a visual effect with white ballerinas.

Adams' former teacher Rayevsky said that her height of 5 feet 5 inches, or 165 centimeters, might be a factor because Russian ballet is particularly picky about its group dancers, who in recent years have become taller and taller on average.

"They have the same body, the same height — they all look the same," Rayevsky said by phone from Michigan.

At least one other African-American dancer has passed through the Bolshoi Academy: Gabe Stone Shayer, who was in Labrador's class of 2012. Shayer, who received more roles at the academy than Adams does and now dances at the prestigious American Ballet Theater in New York, may have helped break racial barriers simply by coming up at a time when the pool of male talent in classical ballet is comparatively smaller.

Bolshoi Pressure

For Adams, the pressure and frustration she feels are joined by the fact that the Bolshoi has gained a reputation for intense competition both on and off stage, especially among ballerinas.

The rivalry for a female role was reportedly behind disputes that led to an acid attack on the ballet's artistic director, Sergei Filin, earlier this year. Principal dancer Pavel Dmitrichenko is accused of and currently on trial for organizing the attack, which severely damaged Filin's skin and eyes and required more than 20 surgeries at a clinic in Germany.

Adams dressed for a performance.

Last week, Izvestia reported that Joy Womack, one of the first American ballerinas to graduate from the Bolshoi Academy, in 2012, and formerly a soloist at the Bolshoi Ballet, said that Filin told her to find a wealthy sponsor or pay $10,000 herself to perform on stage. As a result of her treatment at the Bolshoi, Womack reportedly took a position at the less-prominent Kremlin Ballet Theater.

The Bolshoi Ballet has been a symbol of Russian artistic prowess for nearly 200 years, and while it has occasionally had principal dancers from abroad and its academy now accepts foreigners, the top ballerinas and male dancers are usually Russians who represent a national ideal that does not have room for foreigners or different skin colors. The academy also has numerous students who are the daughters or relatives of former Bolshoi dancers, like Filin's niece, who currently studies at the school.

The battle for performance time is therefore an uphill one for Americans and other foreigners who lack connections in Russian society but are drawn to the academy for its reputation and practice regime.

Rayevsky said he recognized Adams' talent when she was young and suggested she go abroad for training. He said that in a ballet world increasingly combining classical and contemporary elements, the Bolshoi would "give her that background for anything she wants to apply herself to … she will be able to use that knowledge from the Bolshoi Ballet, that discipline."

Adams takes a similar position, arguing that the valuable experience she is gaining serves as an answer to those who question why she came here to train.

"I am really just here to get the best training that I can so I can go and be amazing somewhere else, where it is not so racially discriminatory," she said.

Adams does not plan to stay in Russia after leaving the Bolshoi Academy in the spring, instead looking to Western Europe and North America for a possible position. She remains open to different options but hopes particularly to receive offers from the Canadian National Ballet in Toronto or the San Francisco Ballet, where her younger sister Portia studies.

On Monday, she was invited to go to Switzerland in late January for the Prix de Lausanne, a competition in front of Europe's top ballet companies where the winner can essentially choose her employer.

Drawing support from her family, Adams also gets inspiration from African-American ballerinas who have broken barriers before her. Western dancers are fighting similar, if less severe, discrimination throughout the classical ballet world, and soloists like 31-year-old Misty Copeland, who joined the American Ballet Theater in 2001, have found increasing success.

Some who know Adams think she has a good chance of joining them. Labrador said the most important element of performance for him is "if you make me feel something, and I really feel something from her."

Contact the author at c.brennan@imedia.ru Follow him on Twitter for updates — @CKozalBrennan and @MoscowTimes

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.