KOMSOMOLSK-ON-AMUR — There are few places where Russia's sheer size and its disputed role of a bridge between East and West can be felt stronger than along the Baikal Amur Mainline, but perhaps even fewer places exhibit such isolation and detachment from the rest of the country.

The railroad was built by the Soviet Union as part of an ambitious plan to develop the area so that it would serve as a frontier against China.

It was meant to become the skeleton of this new Russian frontier, a new center to diversify the country that has always been plagued by excessive centralization.

In the Soviet era, Komsomolsk-on-Amur, one of the most eastern stops on this railway, seemed to live up to this expectation as a military hub that produced submarines and planes. Today, it manufactures Sukhoi Superjet 100 as part of the government's effort to re-industrialize its oil-addicted economy.

But with only 37 planes produced since 2008, the factory is not enough for a city that was expected to have 800,000 people and today has only 283,000.

Today's Komsomolsk-on-Amur, originally designated to be the new region's capital, seems nearly deserted, with its Stalinist buildings flanking disproportionately wide streets.

Sergei Lokhmatin, a 25-year-old resident, says business is possible but far from thriving.

"You can do your own business here, but very little industry has survived," he says, explaining that in addition to his primary job, he earns money on the side by driving people around town.

Sergei's comments are the first intimation of shortcomings in the government's plan to turn the region into an industrial powerhouse.

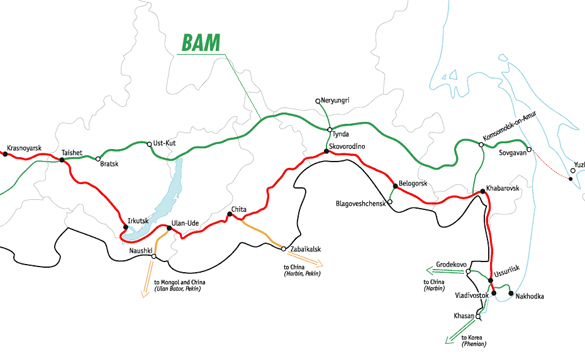

The 5,000 kilometer-long BAM railroad was supposed to create a buffer zone between Russia and the overpopulated China. The railroad currently carries 22 million tons of freight, but according to the ambitious plan put forward by the government, this figure will reach 100 million by 2020. The plan will require more than $10 billion in investment.

The government's plan comes amid increasing competition in the Far East with looming Chinese economic and military might, prompting Russia to focus more on developing its Far Eastern provinces, where the railroad is deemed to be the best way to give a boost to local infrastructure.

The railroad was started by gulag workers and Japanese prisoners of war in the 1930s. But as the Soviet Union's relationship with China went through multiple cycles, the workers followed its ebbs and flows, ultimately abandoning construction sites by Josef Stalin's death in 1953.

After the Sino-Soviet split in the 1960s, the government in Moscow decided to make a final push and the railroad was completed in 1984. The BAM, which over the years has become a subject of patriotic poetry and songs, was the Soviet Union's largest infrastructure project ever.

Families milling about in the sunshine near the building that houses the river port in Komsomolsk-on-Amur.

Vysokogorny, a town of 3,375 people, is a living testimony to that effort. The town, where teenagers roam unpaved streets in old American cars, owes its entire existence to the railway.

The station is full of train convoys of timber, crude oil and more timber. Russian Railways is currently upgrading the facilities to add more capacity. A new 4-kilometer long tunnel has been built near Vysokogorny to increase the allowed trainload.

Some residents say the painstaking efforts put into the railroad hint at a less romantic fact of life in the Far East, however: namely, that the railroad takes precedence over the residents themselves.

"This railroad was built and operates exclusively for raw materials to be delivered for exports," said Andrei, a local resident. "The people that work here matter only to the extent that they serve the railroad."

Kuznetsovsky station once served as one of many hubs for all the workers building tunnels that cross Russia on the way to the Pacific.

But today there is only one house that is still inhabited in this village, by a lonely family of two pensioners who occasionally get visits from their grandchildren.

"I will not leave this place," says Pavel, a Yakut and one of the two residents of this place, which can only be reached by railroad.

Pavel immediately offers a drink, of which he has already enjoyed many, much to his wife's discontent. "Everything is fresh and natural here, all the berries, mushrooms, vegetables!" he proclaims.

Pavel's enthusiasm for his home comes in stark contrast to the sense of disillusionment conveyed by critics of the government's plan to transform the region.

And a population outflow from the area may have them even more concerned: a 2010 census showed a population decline of 155,000 people in the region over the past eight years. As of 2010, about 6.3 million people lived in the Far East, a sprawling region that represents a third of the country's landmass. For comparison, the country's total population amounts to about 143 million.

Gilbert Rozman, a professor emeritus of Sociology at Princeton University in the U.S. who has been closely following developments in the area since the 1980s, says the lack of growth in the region may be due to the fact that Russia's efforts lack a comprehensive policy.

"There is no overarching policy with a realistic change of achieving good results … no serious strategy for modernizing the region, for diversifying the region," he said by phone from the U.S.

"There are often warnings in the Russian media of too much reliance on China, but when you actually look deeper not at what is being said but what is being done, you ask yourself, where is the policy that is going to change this situation?" he said.

Download the higher resolution map here.

Vladimir Zuev, a railroad historian and veteran builder, echoed a similar sentiment aboard the train.

"We thought we would finish the railroad and wake up in another country. And we did, but this new country was no longer the Soviet Union," he said with a hint of irony.

One of Zuev's ancestors worked on the Moscow-St. Petersburg railroad, one of the first ones in Russia.

A product of Soviet space enthusiasm, Zuev devoted his whole life to railroad construction, firmly believing that the effort would make Russia one of the most advanced nations in the world.

But it did not quite work out as he had planned.

"So far, we have not achieved what we intended," he said.

"It's up to the state to make such large-scale projects work; we have lost a whole decade and now have to catch up," he said, adding that the U.S. had always been alarmed by Russia's plans to develop infrastructure in the Far East.

Viktor Larin, director of a Vladivostok-based institute of peoples of the Far East at the Russian Academy of Sciences, believes the Chinese threat — one of the main catalysts for Russia's efforts in the Far East — is mostly an empty one.

It is a pretext used both by President Vladimir Putin and local politicians in a bid to direct Russia's bureaucracy toward the region, he said.

"This process is moving, but very slowly, as it requires a lot of money while there is no clear understanding about what the Far East will be developed for," he said in e-mailed comments.

"There is a strong belief that it is still a colony that must serve the interests of the сenter, but the interests of Russia's elites are in the West, not in the East," he said.

Local residents seemed to agree, expressing the belief that Moscow is exploiting the Far East for its own benefit without giving much thought to the way people there live.

"There is this other state called Moscow," said Yulia Yakhmeneva, chief foreman of a brigade of workers that is constructing new bridges on Sakhalin island.

"It consumes everything," she said, standing on Sakhalin Island before one of the new bridges that she built.

This sentiment was shared by Sergei Daschinskiy, a spokesman for the railroad.

Pointing across the Tatar Strait toward central Russia, he said, "They don't know much about us out there, in the wild west."

Contact the author at i.nechepurenko@imedia.ru

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.