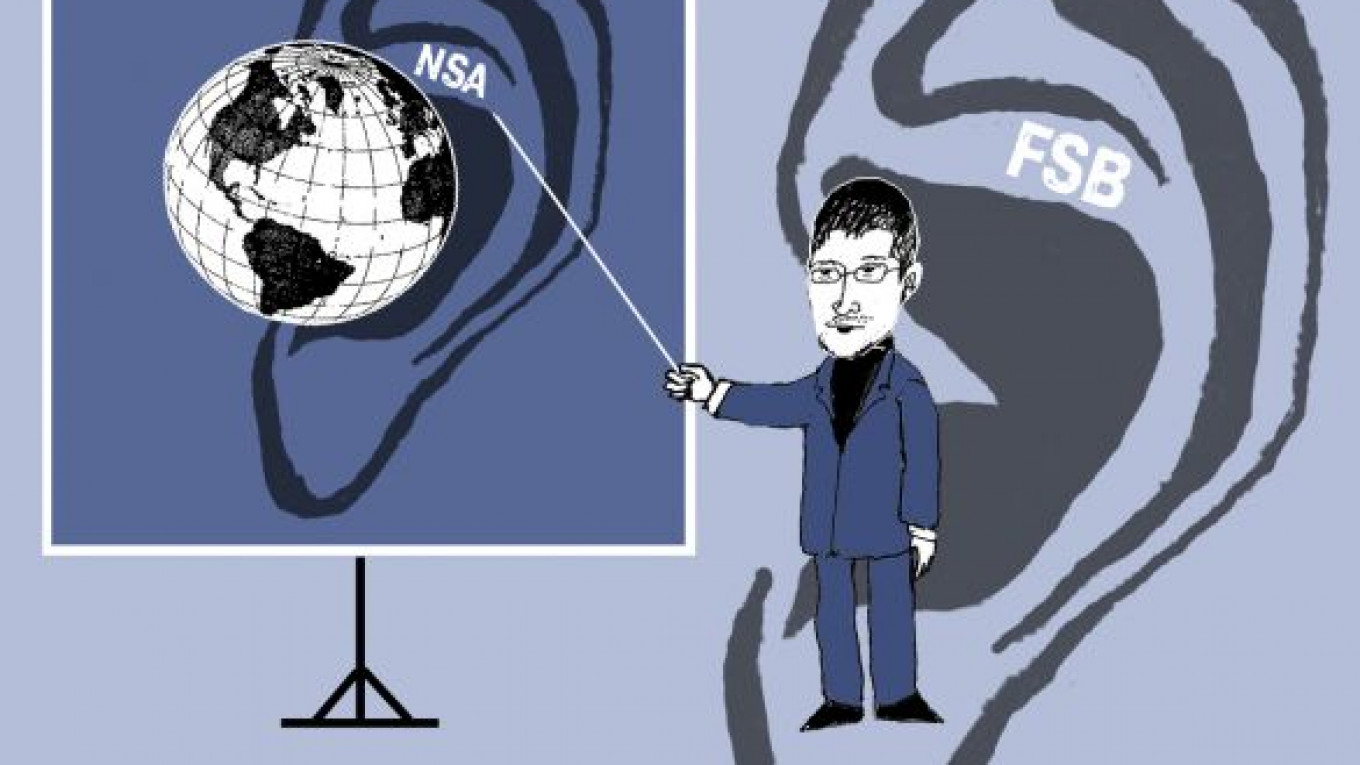

Russia's enthusiastic support for National Security Agency leaker Edward Snowden, including granting him temporary asylum on Aug. 1, seems to be paying generous dividends for the Kremlin.

Thanks to Snowden's recently published leaks, which he claims were handed over to the media before he arrived in Russia, the world learned that the NSA listened in on the conversations of 35 world leaders, their top advisers and millions of foreign citizens. The U.S. targets included allies such as Germany, France, Brazil, Spain, Italy and Mexico. Clearly, this was a dirty, not-so-little secret that the NSA would have liked to have kept classified.

Russia is enjoying a nice windfall from Snowden's cyber-vigilantism and the resulting crisis in U.S.-European relations. It still believes in the old, Cold War-era formula: What is bad for the U.S. is good for Russia.

It is no surprise that the latest Snowden leaks have caused serious problems between Washington and its close allies and partners. For example, when German Chancellor Angela Merkel discovered that her cell phone calls were tapped by the NSA from the early 2000s to June of this year, based on documents that Snowden leaked to Der Spiegel, she was livid and called U.S. President Barack Obama to protest. German Foreign Minister Guido Westerwelle said U.S. actions would be "highly damaging" to relations.

Meanwhile, Le Monde, citing leaks provided by Snowden, reported that the U.S. had intercepted more than 70 million phone calls and text messages of French citizens in just one year. French Interior Minister Manuel Valls said, "Espionage from a friendly country and ally is absolutely unacceptable."

When Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff learned from Brazilian media that the NSA had intercepted her messages and spied on the state oil company Petrobas, she postponed a state visit to the U.S. in protest.

These leaks come on top of other Snowden leaks, released by the media in August, which disclosed how the NSA spied on the United Nations, European Union and the Vienna-based International Atomic Energy Association.

On Wednesday, The Washington Post published a new Snowden leak, showing how the NSA broke into Yahoo and Google data centers located outside of the U.S. Meanwhile, Glenn Greenwald, a columnist for The Guardian and Snowden's chief media liaison, says there will be many more Snowden leaks to come.

Many countries are furious with Washington and are taking action. France and Germany led an effort in the European Parliament to suspend a program with the U.S. that allows it to track the financial transactions of terrorist groups. In addition, the EU announced plans to levy fines up to 100 million euros ($137 million) on Google, Yahoo and other U.S. Internet giants if they turn over Europeans' private communications to the NSA, even when there is a U.S. court warrant to do so. Meanwhile, Germany and Brazil are drafting a UN General Assembly resolution to better protect governments and their citizens from NSA espionage, while Germany's Christian Social Union has even called for the suspension of talks over the huge U.S.-EU trade agreement.

To the extent that the Snowden leaks have put a serious dent in U.S.-European relations, if not U.S. security, Russia is enjoying a nice windfall from Snowden's cyber-vigilantism. The reason that the Kremlin views this as a "payoff" is that it still adheres to Cold War-era, zero-sum game: What is bad for the U.S. is good for Russia.

In their coverage of the scandal, Russian state-controlled media, it would seem, are savoring the new Snowden leaks and the schism that they are causing in U.S.-European relations. In addition, as if to poke the U.S. in the eye one more time, Russia hosted the Sam Adams Award ceremony in early October in which Snowden was honored for his role in promoting "integrity in intelligence."

Thus, President Vladimir Putin was dead wrong when he explained in June why the Snowden affair is not worth his trouble: "It's like shearing a pig," Putin said. "There is lots of squealing and little wool." But, as it turns out, Russia is shearing a lot of wool from the Snowden "pig."

It is not so much the NSA's spying activities per se, but Snowden's leaks about the foreign espionage programs, that have driven a sharp wedge between the U.S. and some of its closest allies and partners. After all, many of the same allies and partners — including Russia — who are crying "Foul!" the loudest are the ones who regularly spy on the U.S. The only difference, of course, is that in these countries, there are no "Snowdens" to spill the beans, and so we are unaware of their espionage practices.

Russia refuses to acknowledge the fact that Snowden broke U.S. espionage and other laws when he leaked classified information about legal spying programs that relied on court orders. As problematic as spying on foreigners is from an ethical perspective, it is not illegal under international law and is practiced by nearly every nation.

Russia, of course, is no exception. For example, the Italian newspaper Corriere della Sera reported Tuesday that Russia gave Group of 20 delegates complimentary USB flash drives and mobile phone chargers during the September G20 summit in St. Petersburg. According to German intelligence, which examined the devices, they carried malware that would allow Russian authorities to capture the foreign delegates' data from their mobile phones and laptops.

Indeed, everyone spies on each other. The only difference, of course, are the capabilities and tools used by each country's intelligence agencies. If the KGB rivaled the CIA in many areas during the Cold War, the gap between Russian and U.S. intelligence-gathering capabilities, particularly in high-tech signals and communication intelligence, has grown exponentially since the Soviet collapse.

While the U.S. uses highly advanced technology to gather communication intelligence, Russia apparently resorts to passing out malware-infected thumb drives to G20 delegates, or sending "sleeper agents" like Anna Chapman to "infiltrate" the U.S.

This intelligence-capabilities gap is a real sore spot for the Kremlin, which helps explain why its support for Snowden and his campaign against U.S. intelligence-gathering programs has been so ardent.

Notably, while Russia was experiencing Schadenfreude over U.S. spying on its allies, the Communications and Press Ministry released a draft government order last week that will allow the FSB access to the content of Russians' telephone calls, e-mails, instant messages and other Internet communications without a court order. Internet providers would be forced to install equipment on their servers that would provide a direct link to the FSB. This directly contradicts a statement that Putin made during his June interview with RT television that the government is prohibited by law — namely, Article 23 of Russia's Constitution — from eavesdropping on Russians without a court order.

Although independent intelligence experts such as Andrei Soldatov say the FSB always had a free hand for the past 15 years to intercept Russians' Internet communications and phone calls, the new order will make it much easier to do so. Once implemented, the FSB's expanded powers to spy on Russians would be a gross violation of their constitutional rights to private, confidential communications.

It would be interesting to find out how Snowden feels about this latest FSB spying program. After all, ever since Snowden disclosed himself in early June as the NSA leaker, state-controlled media and Kremlin-friendly political analysts have tirelessly praised him as a "privacy-rights defender who bravely fought against the state's abuse of spying."

This begs the rhetorical question: When will Snowden find the courage to speak up against Russia's spying abuses? After all, 60 million Russian Internet users and more than 100 million owners of cell phones are counting on the world's "bravest" and most outspoken privacy-rights defender to defend their rights.

Michael Bohm is opinion page editor of The Moscow Times.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.