On Oct. 8, a verdict was announced in the case of Mikhail Kosenko, one of the demonstrators in the May 6, 2012 protest march at Moscow's Bolotnaya Ploshchad. Kosenko was just one of the 28 people accused in the case, but his verdict was immediately picked up by the press and caused mass protests outside the courtroom. The crowd chanted "Misha!" so loudly that Judge Lyudmila Moskalenko could barely be heard in the courtroom.

Kosenko is 38 years old. While serving in the army he suffered a head injury, which resulted in mental illness and depression. For the last 12 years he has been under the care of a psychiatrist, who prescribed antidepressants and a mild sedative to help him sleep. On May 6, 2012 he was on Bolotnaya Ploshchad, arrested, paid a fine and went home. But on June 8 of that year, Kosenko was arrested again, this time accused of the more serious crime of participation in mass riots and resisting police officers.

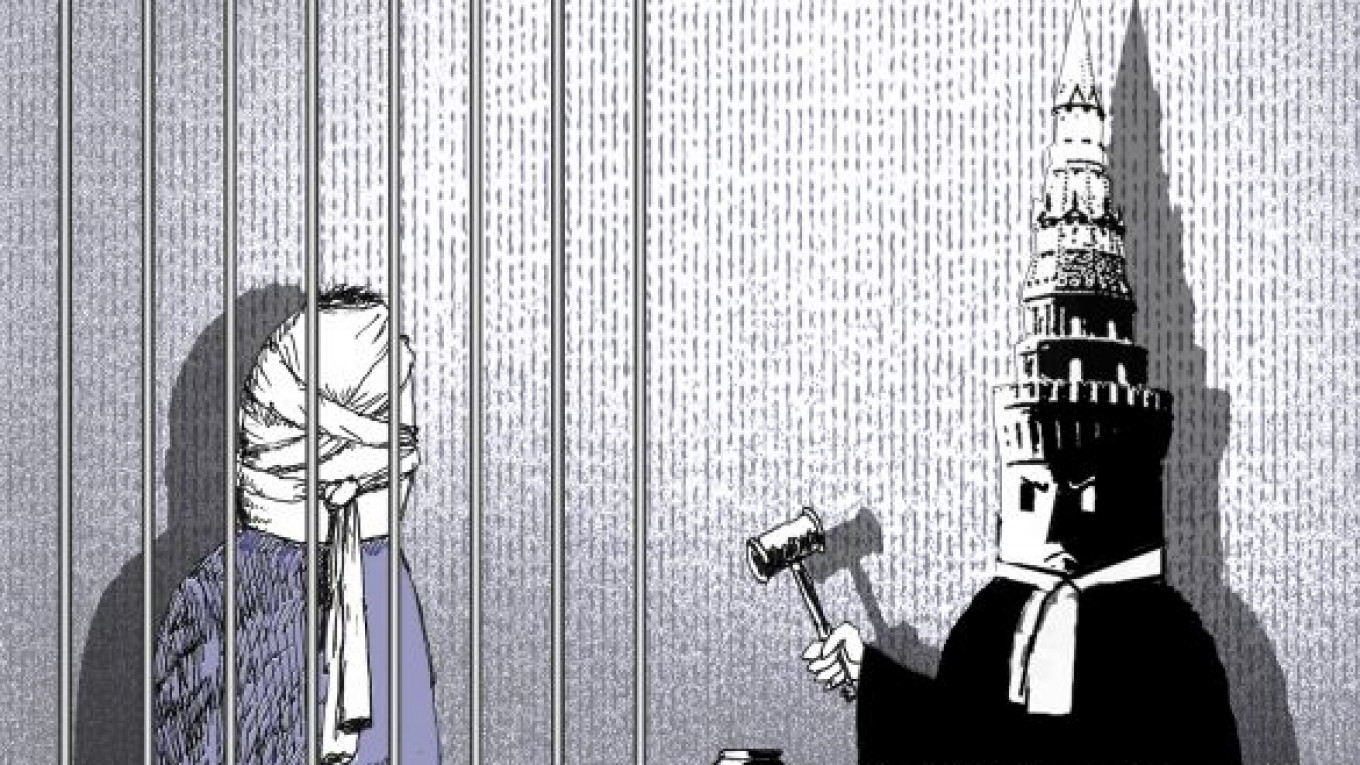

The trial of Kosenko has become emblematic for many reasons. For one, its legality is right out of the Franz Kafka playbook. For many months, the judge did not permit the defense to question witnesses who stood next to Kosenko on May 6 or to view a video that captured the incident used to incriminate him.

At the very end of the trial, the witnesses were heard and the video was finally viewed. Both proved Kosenko's innocence. Kosenko stood at a distance of at least 10 meters from the police, who scuffled with other demonstrators. The witnesses, including Alexander Podrabinek, a prominent Soviet-era dissident and currently Radio France Internationale commentator, testified that Kosenko stood next to him and did not brawl with police. Nevertheless, all this seemingly irrefutable testimony was dismissed by Moskalenko.

During the trial, Kosenko's elderly mother became ill. The judge refused to grant her permission to see her son. She died on Sept. 5. Kosenko's lawyers and Dmitry Muratov, editor-in-chief of Novaya Gazeta, asked the judge to allow Kosenko to attend his mother's funeral, taking full personal responsibility for him. But the judge did not allow it.

Specialists from the Serbsky Psychiatric Institute played an even more Kafkaesque role in the Kosenko case. Specialists from the institute, which was notorious during the Soviet era for its leading role in punitive psychiatry, made a highly questionable diagnosis after just one brief conversation.

The Independent Psychiatric Association of Russia issued a special announcement on the case. "On the basis of a conversation that lasted less than one hour, the specialists made the far more serious diagnosis of paranoid schizophrenia instead of the diagnosis of sluggish neurosis-like schizophrenia that Kosenko was treated for over the course of 12 years." Even more dubious was the Serbsky Institute's conclusion that Kosenko "required compulsory treatment" since "he presented a danger to himself and others."

This conclusion not only contradicted the diagnosis of the psychiatrist who has treated Kosenko for many years, but also ignores his behavior in prison. In 16 months of pretrial detention in Butyrka prison, Kosenko was not once cited for aggressive or suicidal behavior. He did not have a single serious conflict with either the prison administration or his cellmates.

All the same, the court trusted the recommendations of the Serbsky Institute specialists and sent Kosenko for open-ended treatment in a psychiatric hospital.

Public opinion was summed up by politician and businessman Mikhail Prokhorov in his blog on the Ekho Moskvy radio station website, "Sending someone for compulsory psychiatric treatment is a form of punishment that was used only by the Soviet repressive machine in its fight against dissidents."

In the Soviet period, punitive psychiatry was so widespread that one fourth of the dissidents accused of political crimes were declared "mentally ill." Even more widespread was the practice of compulsory hospitalization without court order, done simply on the orders of the KGB. Each year the highest authorities in Moscow sent up to 1,000 people to psychiatric hospitals. These were people who had come to capital to fight for justice denied in their hometowns. The same situation could be observed in the provinces.

Forty years ago Vladimir Bukovsky, well-known for his battles against the political abuse of psychiatry, explained why using psychiatry against dissidents was so useful for the KGB. Hospitalization did not have an end date, so there were cases of dissidents incarcerated in psychiatric prison hospitals for 10 or even 15 years. And more important, the dissidents were subjected to "treatment" — strong drugs that damaged their mental capacities and suppressed their free will.

And now as repression of the country's new opposition activists is heating up, the Kremlin has dusted off this handy old tool to put down dissent.

The only thing they failed to take into account is that this "tool" of punitive psychiatry is effective only when it is used in secret. The iron curtain has long been torn down. Kosenko's case immediately became known to human rights organizations and the international media.

In this situation, punitive psychiatry works more against the Kremlin than against the opposition. It makes mockery of the Kremlin's attempts to "improve the image of Russia abroad" and paints a realistic picture of the country today — an authoritarian dictatorship with nearly medieval methods of fighting dissidents.

Victor Davidoff is a Moscow-based writer and journalist who follows the Russian blogosphere in his biweekly column.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.