In the Soviet Union, you couldn't pay for schooling even if you wanted to. After the fall of the socialist empire, private education appeared, but free, public schooling was still available to all.

As a new law comes into force regulating Russia's education system, critics of it fear that a good education may now become a privilege you need to pay for.

The law, which came into force Sept. 1, in time for the start of the new school year, will replace legislation passed in 1992 that guarantees free access to pre-school education, eight-year schooling and vocational education, as well as to higher education on a competitive basis. The 1992 law also makes a basic eight-year school education compulsory and establishes its secular nature.

The Education and Science Ministry insists that these principles remain in place with the new law. But critics say the law in fact nullifies all of them.

"The most terrible thing is that the new law on education violates the Constitution," argued Yelena Klimova, an activist in the Kaluga region who co-authored an open letter against the law to President Vladimir Putin in May.

"Now authorities can do anything they want with education. They have the law," Klimova said.

The contradictory interpretations stem from the complex language of the 142-page legislation, which institutes often subtle changes in all levels of education, from pre-school to universities. The Education and Science Ministry says the law will expand opportunities for students and make essential changes to the education system.

"We are prepared for the transition to the new law," said Natalya Tretyak, a first deputy education and science minister, at a press conference Friday, RIA Novosti reported. "We have been awaiting this transition and are confident that work under the conditions of the new law will be to the benefit of our students, teachers and all of society."

When asked about the divergent views on the law, an Education and Science Ministry spokesman referred a reporter to an explanatory brochure posted on the ministry's website.

The brochure says education remains free of charge on all levels but the law only guarantees the general availability of vocational education without mentioning pre-school education, basic eight-year schooling or higher education.

The law seems to create a loophole by saying that educational organizations "have the right … to provide generally available and free basic and vocational education" but failing to oblige them to provide it.

"The free-of-charge basis is guaranteed only by the letter of the law," Oleg Smirnov, an expert with the All-Russian Education Fund, said by telephone.

"The main educational aspects rest upon additional education, which is, for that matter, not free of charge," Smirnov said.

Smirnov was referring to the fact that only a certain set of classes defined by the government is guaranteed to be free for students.

The emergence over the years of additional classes that require payment from students' families is a major concern for many Russians. In a Levada Center poll conducted in May, respondents were asked to name the biggest problems in schools: the top answer was "the rise in additional education-related expenses," cited by 47 percent of those surveyed.

Government Take

The Education and Science Ministry brochure names nine main benefits of the new law, including the introduction of new forms of education, such as distance-learning, and increased availability of pre-school and professional education.

Yelena Shimutina, deputy director of the Moscow state secondary education center Tsaritsyno and head of the Institute for Development of Joint State and Public Management of Education, a nongovernmental think tank, praised these new features, such as the introduction of computer technologies.

In her view, other advantages include the right to get state financing to study at private schools; the right for school and university students to choose their subjects of study; broader powers for parents and students to influence the educational process; and additional opportunities for disabled children to access education.

Oleg Smolin, first deputy head of the State Duma's Education Committee and a member of the Communist Party, said the new law allowed authorities to provide talented children with additional educational opportunities, although it would not guarantee such opportunities.

The 1992 law "created conditions for the self-government of schools and the appearance of experimental educational methods" but "there was no financial and organizational basis for the implementation of these initiatives, and many progressive ideas remained on paper," the ministry's brochure said.

According to the brochure, the new law is also aimed at the "integration of the Russian and the European educational environment." In particular, the law facilitates the mobility of students and professors and the implementation of joint educational programs with foreign institutions.

Public Concerns

The Education and Science Ministry submitted the draft law to the State Duma in August 2012, after two years of public discussion. Putin signed the law in December.

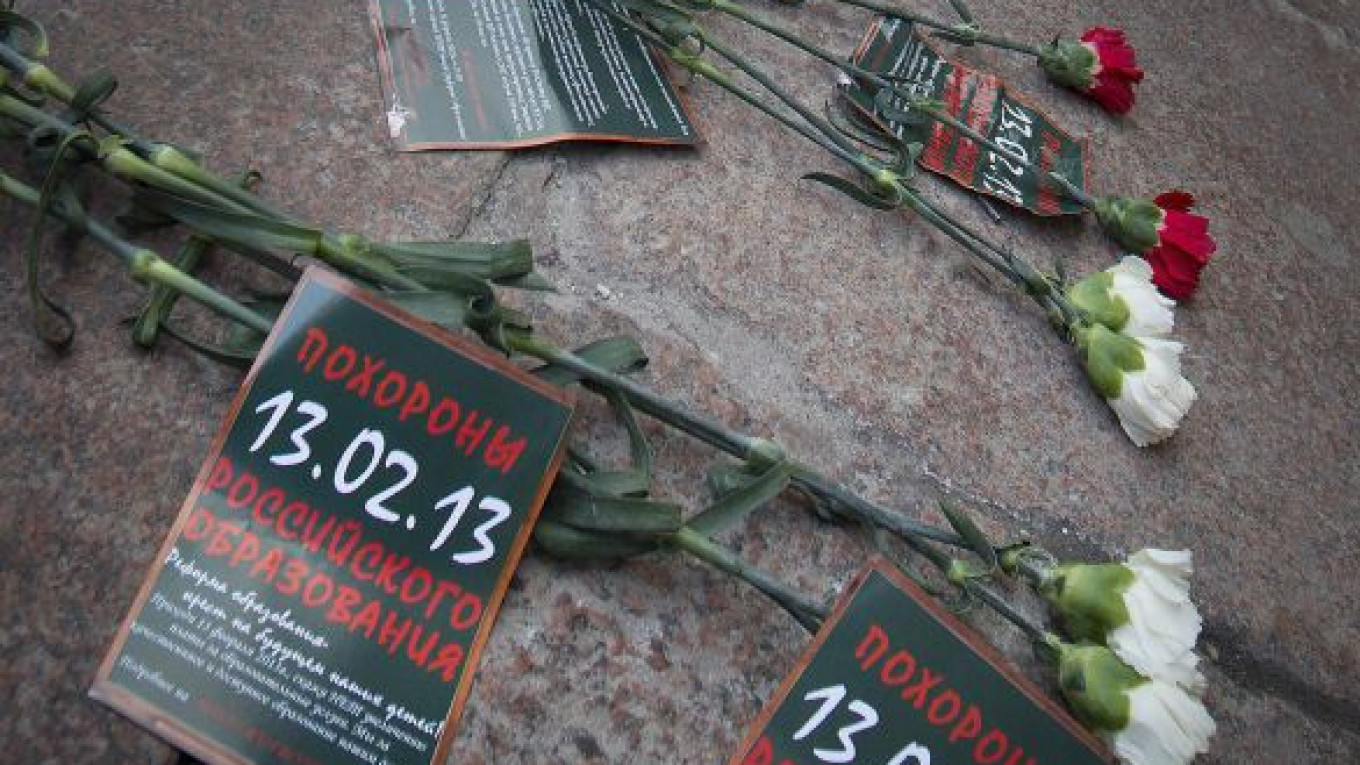

In February of this year, a group of more than 15 professors, lawyers and parents from several regions sent a letter to Putin warning him that the new law makes a basic eight-year school education nonmandatory, "relieves the state of the responsibility" to finance education and does not set universal educational standards, among other shortfalls.

By early April, the group that penned the letter had drafted amendments to the law and sent them to several state and public agencies, including the Kremlin, the parliament, the government human rights ombudsman, and the Public Chamber, according to Klimova, the Kaluga region activist.

Klimova is part of a group called the Civil Initiative for Free Education, which in a statement also spelled out what it believes to be the "dangers" of the new law.

One such pitfall it cites is the likelihood of pre-school education becoming "inaccessible" for children from low-income and middle-income families because, the group says, the law gives municipal authorities the right to "set any pay" for a kindergarten and allows them to refuse a child a place in a kindergarten.

The group is also concerned that the new law allows religious education in secular schools. Under the law, the government can oblige a pupil to study one of the major religions in Russia, as chosen by the pupil. The program of religious studies is then approved at a "centralized religious organization" of the relevant confession.

"This article of the law is simply outrageous, even for believers, not only for atheists," Klimova said.

Klimova's group says another danger is that small, rural schools may either be closed or will have to be financed almost completely by parents because the law introduces a system under which schools receive state funding based on the number of students they have.

The number of schools in Russia has been on the decline for more than three decades. According to state statistics, in 1980 there were just under 75,000 secondary schools in the country, while this year fewer than 45,000 will open their doors to students. Since last year, more than 700 schools closed due to lack of students, with about 250 of them in villages, Chief Sanitary Inspector Gennady Onishchenko said last month.

Shimutina of the Tsaritsyno education center believes that the law's aim is "optimization" of state expenses on education, which "does not necessarily mean cutting expenses."

"It can be the reshuffle of resources in order to achieve a better result for the same money," she said. "Some expenses can be cut but not for the sake of cutting."

Contact the author at n.krainova@imedia.ru

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.