One of the more ridiculous aspects of the Edward Snowden affair has been Russia's feigned and exaggerated indignation over his revelations that the National Security Agency conducted a spying campaign aimed at Russia and other foreign countries.

Reflecting the widespread opinion of many pro-Kremlin political analysts, Igor Korotchenko, editor-in-chief of National Defense, called the NSA "a global electronic vacuum cleaner that monitors everything."

Going further, retired KGB lieutenant general Nikolai Leonov said during a prime-time talk show on state-controlled Rossia television, "The U.S. behaves like a mafia kingpin on a global scale."

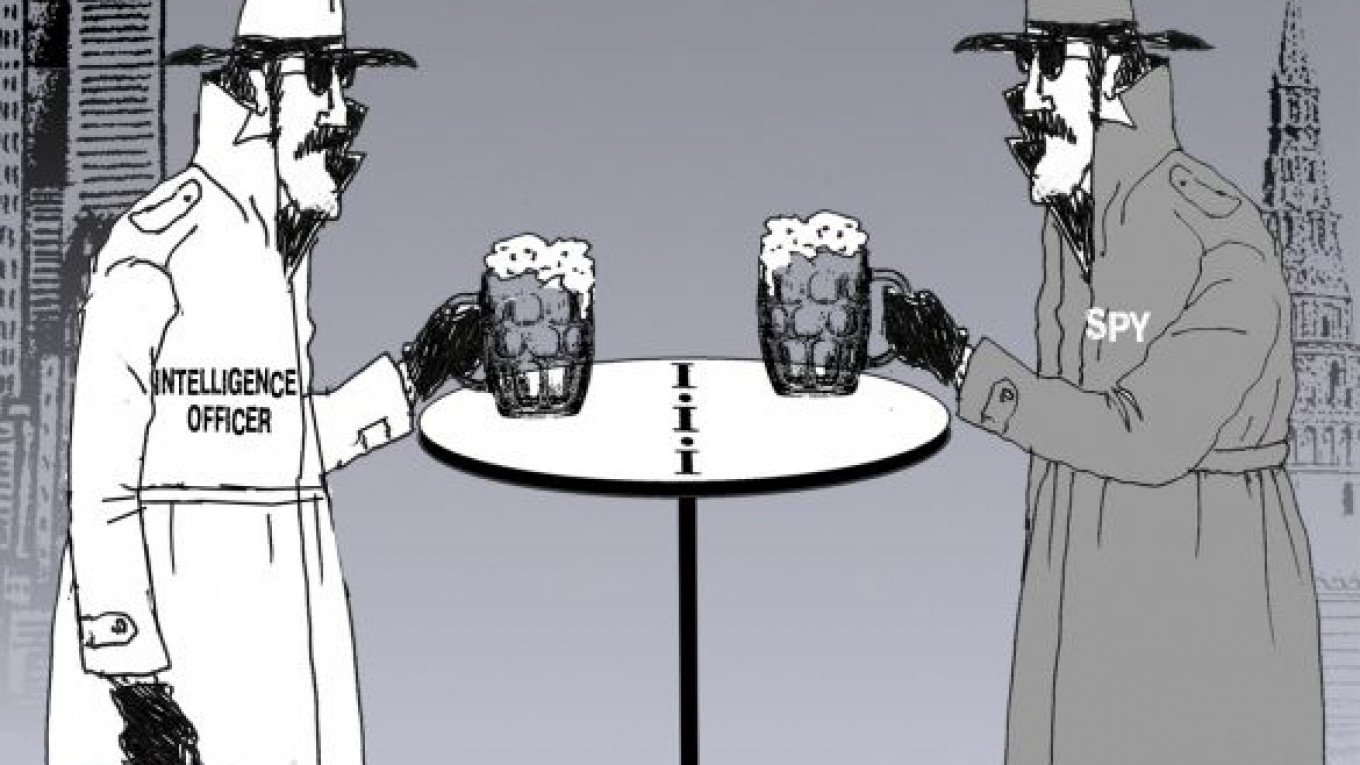

Russia's fervent objections to the NSA's foreign espionage activities show a clear double standard — just like the old Russian quip that when U.S. agents gather foreign intelligence, they are "spies," but when Russian agents do the same thing, they are respectfully called "intelligence officers."

The problem with these arguments, however, is that the type of spying on foreigners that Snowden revealed is not a violation of any international law, treaty or convention. In the absence of any legitimate legal claims against the U.S., Russia's protests against the NSA are reduced to a flimsy argument: It is "bad" to spy on others.

Russia's argument against the NSA is particularly absurd and hypocritical given that Russia, like many other countries, actively gathers intelligence in the U.S. In fact, independent intelligence analysts estimate that the current level of Russian espionage against the U.S. has reached Cold War-era levels. What's more, roughly 95 percent of Russia's foreign espionage is done with NSA-like electronic and communications intelligence methods, according to Alexei Filatov, a retired FSB colonel and head of the Alfa anti-terrorist veterans association. But the main problem, Filatov said, is that Russia is far less successful than the NSA at intelligence gathering.

In condemning the NSA, many Russian analysts ignore the fact that there is a fundamental difference between the domestic and foreign NSA surveillance programs that Snowden leaked. The Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution only protects Americans from the U.S. government reading their mail or listening to their phone calls without a court order. (Snowden revealed no evidence that Americans' Fourth Amendment rights were ever violated by the NSA programs.) But, for better or worse, the Fourth Amendment does not apply to Russians and other foreign citizens, so there is no legal basis to claim that spying on Russians is "illegal."

One option, in theory, would be to sign a bilateral U.S.-Russian agreement that would limit spying on each other — something along the lines of U.S.-Russian treaties that limit nuclear weapons to a certain level. But the framework that has worked for decades in the area of nuclear disarmament has never worked in the spying game. Espionage, which does not lag far behind prostitution as mankind's oldest profession, has always been a necessary evil in international relations. As long as one side is doing it, the other side will as well — with few restrictions.

Indeed, efforts to legally limit foreign espionage has been an exercise in folly. Even among the closest of allies — the U.S., Britain, Canada, Australia and New Zealand — the most these countries can agree on is a nonbinding "gentleman's agreement" not to spy on each other. Early this month, Germany proposed signing a "no-spy" agreement with the U.S, but this is expected to produce only another toothless "gentleman's agreement."

Matters are much worse between the U.S. and France. Although the two countries are allies, they still have a long history of spying on each other's diplomats, politicians and military interests. (The same goes for the U.S. and Israel.) Even France's decision to return to NATO's military command in 2009 did little to limit the espionage activity against each other.

If close allies can't agree on a binding treaty to limit spying, an agreement between Russia and the U.S. is even more inconceivable.

"Look at the top two floors of the new building of the U.S. Embassy," Korotchenko lashed out during an interview on Russian News Service radio several weeks ago. "It's a huge antenna that listens in on all of Moscow." Intelligence experts say the Russian Embassy in Washington is equipped with similar listening devices.

In reality, foreign espionage has always been considered a "sovereign right" of every country. On occasion, even Russian officials admit this fact — particularly when they have been caught spying themselves. Thus, Russia's fervent objections to the NSA's foreign espionage activities show a clear double standard — just like the old Russian quip that when U.S. agents gather foreign intelligence, they are "spies," but when Russian agents do the same thing, they are respectfully called "intelligence officers."

Spying on each other is so systemized and accepted as a "sovereign right" that the U.S. formally presents the head of its CIA station chief when he takes up his position at the U.S. Embassy in Moscow to Russian officials. It is clear that the CIA chief has a full staff of officers in the U.S. Embassy and consulates whose objectives are obvious. The same goes for Russia's foreign-intelligence operations in Washington and other U.S. cities.

The espionage race between the U.S. and Russia is not unlike the Cold War-era arms race between the two superpowers. But in the absence of bilateral treaties limiting spying activities, which neither side has an interest in signing, the Kremlin has only two options available: ratchet up its own efforts at gathering foreign intelligence and improve its counter-intelligence measures against U.S. surveillance.

In terms of countermeasures, Russia needs to outsmart the U.S. at its own game, which in many cases it does successfully. Take, for example, when Snowden revealed in one of his leaks that the NSA tried to eavesdrop on then-President Dmitry Medvedev during the 2009 Group of 20 summit in London. In reality, the NSA's attempt was fruitless because it was unable to break Russia's code.

Pro-Kremlin analysts also like to complain that the world's leading Internet companies have their headquarters — and, most important, servers — in the U.S. This, the argument goes, gives the NSA an "unfair advantage" in spying on foreign governments and citizens, who "are forced" to use the Internet services of these U.S.-based companies.

Instead of complaining about this "injustice," however, Russia should instead try to break this near-monopoly by creating its own Silicon Valley to compete with Microsoft, Yahoo, Google, Facebook and Skype. (Brazil, for example, has taken the lead in trying to develop "Internet sovereignty" from the U.S.) But this will require more than throwing billions of dollars at Skolkovo. It also will require that Russia's top IT talent stays in Russia and not emigrate to Silicon Valley, Boston and other global IT centers that offer better opportunities.

When Alexei Filatov, the retired FSB colonel, was asked during a recent interview on MIR-TV why Russian officials and pro-Kremlin analysts were so up in arms about PRISM, the NSA foreign espionage program that Snowden leaked, Filatov answered that Russian officials were just envious about the huge capabilities gap between the NSA and Russia's equivalent intelligence agencies.

Indeed, Russia's disingenuous reaction to the NSA's foreign intelligence-gathering activities is like a boxer who trains all year for the big match against his arch-rival, and, after he is knocked out in the third round, claims that boxing is "bad" because it is a violent sport.

Michael Bohm is opinion page editor of The Moscow Times.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.