We can always count on the Americans to do the right thing, after they have exhausted all the other possibilities," Winston Churchill once famously remarked.

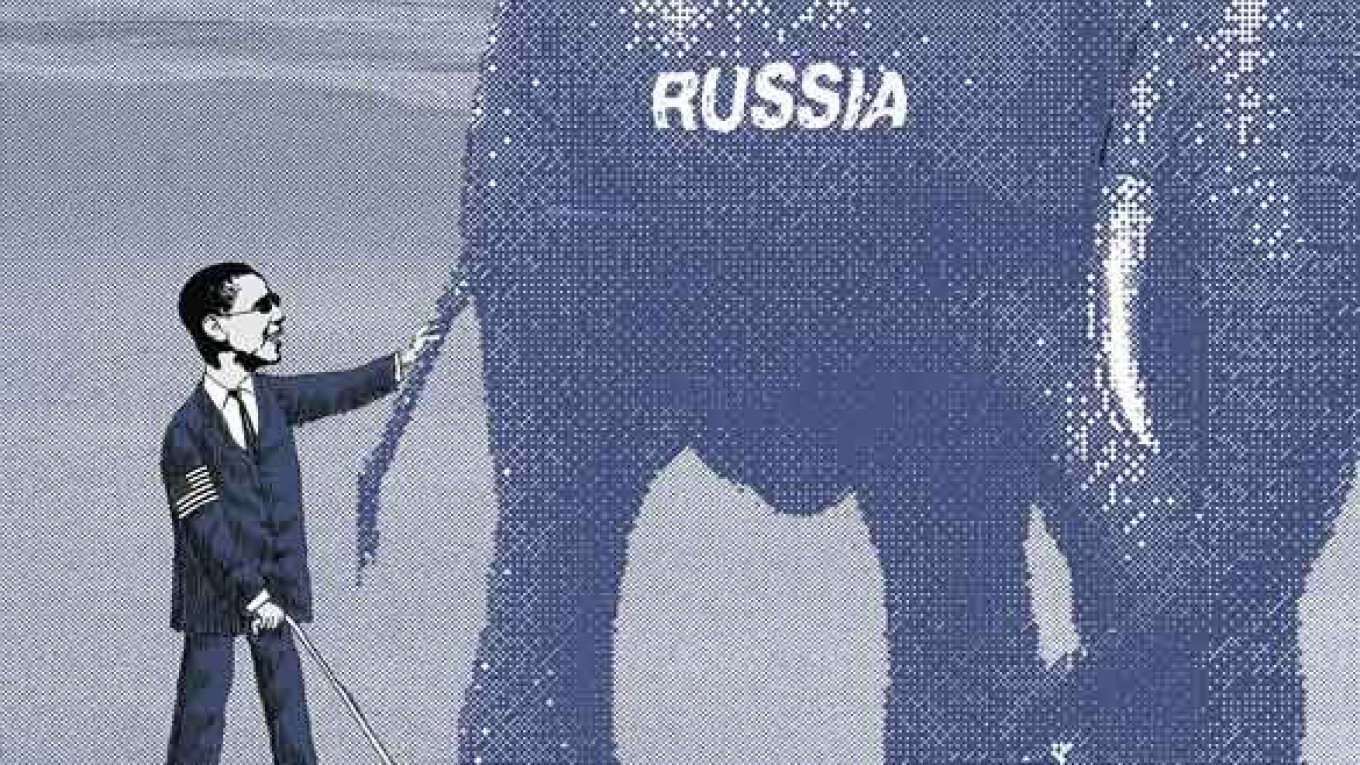

In light of that dictum, we are still at the exhausting-other-possibilities stage — at least with regard to U.S. policy on Russia. Doing the right thing in this area appears to be as remote as ever. During the Cold War, the rhetoric on U.S. right and left somewhat balanced each other, but today they are practically unanimous: President Vladimir Putin's Russia is bad, and the only way to deal with it is to contain it politically and economically using freedom and democracy promotion slogans as cover.

The U.S. political establishment stubbornly sticks to this position, blindly ignoring the disastrous failures of color revolutions in several former Soviet republics and the equally disastrous results of the "Arab Spring." The prevailing attitude in Washington is: The democracy show must go on, and damn the realities.

As Sean Scallon rightly noted in the Aug. 20 issue of The American Conservative, U.S. foreign policy became very confused after the end of the Cold War. The White House's flawed Russia policy has caused considerable damage to U.S. security interests. Russia is the only country in the world that has achieved parity with the U.S. in terms of nuclear warheads. This by itself must imply careful handling of U.S.-Russia relations. Putting off negotiations in Moscow on nuclear arms reduction was extremely irresponsible on U.S. President Barack Obama's part, particularly given the fact that he received the Nobel Peace Prize. Another important reason why such unwise behavior by Obama undermines U.S. security interests is that it pushes Russia into China's welcoming embrace, the two countries edging toward a powerful, U.S.-unfriendly alliance.

One would have thought that the end of communism and the collapse of the Soviet Union was the right time to grab huge peace dividends by integrating Russia into the Western orbit. But every U.S. president after Ronald Reagan chose an anti-Russian policy to one degree or another.

NATO's eastward expansion was perhaps the most egregious error in U.S. foreign policy, but there were smaller mistakes as well, such as Obama's recent summit cancellation and his announcement that the U.S. needs to take a "pause" in the "reset" to re-evaluate relations with Russia.

The other mistake was the U.S. unequivocal support for anti-Russia leaders such as Georgian President Mikheil Saakashvili during the 2003 Rose Revolution and Ukrainian President Viktor Yushchenko during the 2004 Orange Revolution. The failure of these policies became evident once these "democratic heroes" who were spun so actively by U.S. propaganda, disappeared from the political scene.

The other anti-Russia component of U.S. foreign policy is Washington's intention to weaken Russia's financial well-being and international standing — not through some covert CIA operation but through urging European Union and NATO countries to dump Russia as their energy supplier and to switch to alternative sources of energy.

Few in Washington care whether the alternative oil and gas suppliers are democratic or not, as long as they squeeze Russia's position in the global energy market.

Certain members of Congress are just as outspoken on this score as Obama. "Our policy will promote the energy security of key U.S. allies by helping reduce their dependence on oil and gas from countries such as Russia and Iran," Senator John Barrasso said.

Representative Ted Poe chimed in, saying: "The risk of high reliance on Russian gas has been a principal driver of European energy policy in recent decades … From the U.S. perspective, cheap but reliable natural gas would reduce Moscow's clout while shoring up goodwill among our allies."

Azerbaijan, which leaves a lot to be desired in terms of human rights and democracy, nevertheless has full Senate Foreign Relations Committee praise as a reliable gas supplier for NATO countries that will "fend off reliance on Russian gas."

So despite all the talk about a reset in U.S.-Russian relations, U.S. geopolitical strategy is still dominated by blind, outworn instincts of the 19th and 20th century Great Game. With or without the Communists in power, Russia is still the bad guy that must be contained and weakened.

How can we expect cooperation from Putin on Syria, Iran, Edward Snowden or a variety of other issues when we are openly trying to undermine him both politically and economically?

If we wait long enough, Washington may eventually do the right thing in terms of its Russian policy — but only after exhausting all the other possibilities.

Edward Lozansky is president of the American University in Moscow and professor of world politics at Moscow State University.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.