A recent exhibition of work by St. Petersburg-based underground arts group New Artists, active between 1982 and 1990, was intended to be a homage to the rebellious spirit of artists during the last decade of the Soviet era. Instead, it resulted in lawsuits when four artists discovered works that they thought they had lost displayed at the state-owned Research Museum of the Russian Academy of Arts.

"Assa: The Last Generation of the Leningrad Avant-Garde" was held in May and June and was organized by Sergei "Afrika" Bugayev, who was also a member of the group. It was organized under the aegis of his Institute of New Man, a virtual organization involved in mounting exhibitions, performances and lectures.

Intended to re-establish the reputation of the controversial Bugayev as one of the seminal figures of the perestroika era's explosion of underground art and music in Leningrad, the exhibition resulted in yet another controversy, adding a rather new attribute to the image of the underground artist-cum-art dealer and pro-Kremlin sycophant.

The artists Oleg Maslov, Inal Savchenkov, Oleg Zaika and Evgeny Kozlov have filed lawsuits against Bugayev and the venue, demanding that 25 works made in the 1980s be returned to them.

They believe that Bugayev misappropriated the works during the late 1980s and early 1990s, when he was active in presenting Russian underground visual art abroad and is believed to have become friends with many Western art dealers and gallery owners. Many artworks never returned from those exhibitions, with Bugayev offering different explanations until the losses were forgotten, say the artists.

A number of exhibitions were held in Western art galleries during the perestroika years and early post-Soviet period, with artworks secretly taken across the border via diplomatic mail or represented to customs officials as decorations for concerts by Pop Mechanics, Sergei Kuryokhin's flexible avant-pop ensemble that included both musicians and artists.

When the works believed to have been long lost reappeared on the walls of the Research Museum gallery, they were listed as coming "from the private collection of Sergei Bugayev" in the exhibition catalog.

"There is a long list of my 'lost' works from the 1980s," Kozlov said via e-mail from Berlin on Saturday.

"I have always suspected that Sergei Bugayev, 'Afrika,' [holds] at least several of them because of the information gathered in the 1990s by the German art critic and curator of my work, Hannelore Fobo. At that time, she exchanged letters with the organizers of the New Artists exhibitions in Stockholm (1988), Denmark and Liverpool (1989). She inquired about my paintings, since they had not been returned to me. As we all know, Bugayev accompanied these exhibitions as an artist and musician, and these letters gave evidence of the fact that he gave away my paintings or sold them as if he were the legal owner, which, of course, he was not."

"Now, many journalists wonder why there is no way to settle the conflict with Bugayev over a nice cup of tea. We would have loved to do that! Alas, not only has he ignored all my attempts to find out which of my works he [has], including Fobo's letter from March 2012. On top of that, when Andrei Khlobystin called him in July and suggested [he] simply give back the paintings by Oleg Zaika, Inal Savchenkov, Oleg Maslov and myself — 25 altogether, five of which are mine — Bugayev literally invited us to take legal action before the courts. He refuses to avoid a scandal and says we just want to see our names in the press.

"I would like to make two points very clear. First, we are not talking about any paintings in the collection of the State Russian Museum, as Bugayev constantly claims — neither in my case nor in that of the other artists. We are talking about works that reappeared unexpectedly after 25 years in the Assa exhibition, organized by Bugayev. Secondly, if Bugayev wants to organize exhibitions with my paintings, this is perfectly fine with me as long as he acts in a professional way and signs a loan contract with me. Instead, in an interview with Sankt-Petersburg Television, he calls our action 'the screaming of some strange sort of animals, little jackals, wishing to attack a proud animal.'"

The reappearance of the long forgotten works in such number at the exhibition came as a surprise to their authors, according to artist and art historian Andrei Khlobystin.

"These works are from the 1980s, and no one has seen them since then. Many people forgot even to think of them; it was some 20 years ago," said Khlobystin, who is the plaintiffs' media representative and negotiator.

"And now, all of a sudden, they have surfaced at the exhibition and in the catalog, so the artists rejoiced thinking that they could get them back. Many knew that these works existed, but did not suspect where they were. For many it was not a surprise— [Bugayev] is known for selling other people's artworks. He just made a mistake in displaying them all together. Perhaps he believes in his absolute impunity."

According to Khlobystin, it is the fact that the artworks were displayed that made it possible for the artists to sue Bugayev.

"Many artists have had claims on him, but could not file complaints," Khlobystin said.

"It was the 1980s, and even the photographs of the works did not survive, not to mention any documentation. The police would laugh if someone came and started describing, say, some skull driving a nail into itself or beating itself with a dumbbell. It would be ridiculous."

The artists believe that Bugayev has many more paintings in his possession that belong to other people.

"For instance, I know that he holds some of my works," Khlobystin said.

"I think we can speak about dozens of works, at least. He exhibited a small portion of what he has at the Academy of Arts. Some artists died and cannot complain. But one artist who is now abroad wrote to me: 'Yes, I see the works that I have never given to anybody. How could he get hold of them?' He can make a statement, if he wishes."

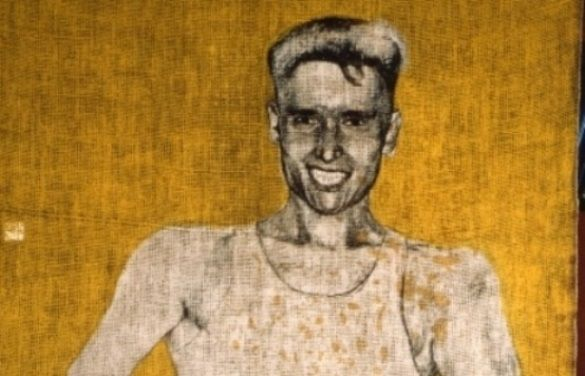

A portrait of the artist Georgy Guryanov is one causing the controversy.

Kozlov, the Leningrad-born, Berlin-based artist, believes that five paintings belonging to him, including his iconic portrait of the recently deceased artist and musician Georgy "Gustav" Guryanov, are now unlawfully possessed by Bugayev.

The first court hearing of Kozlov's lawsuit, on Thursday, Aug. 8, was brief and focused on technicalities. Judge Olga Knyazeva ruled that the case be heard by Judge Anna Isayeva, who is handling the second lawsuit filed by the other three artists, which will resume Aug. 27. The first hearing of the second lawsuit filed by the other three artists took place Monday, Aug. 12.

According to the lawyer for artist Andrei Vasilyev, the two lawsuits are likely to be united into one in the course of the trial. Speaking to journalists outside the courtroom, Vasilyev, who is the director of Vasilyev Legal Group, said the four artists are suing only Bugayev and the Research Museum of the Russian Academy of Arts for the return of their artworks, not for any financial compensation.

However, the representatives of both "categorically" refused to return the paintings to the artists, but made no further comment to either the court or the plaintiffs, Vasilyev said. Bugayev has also declined to comment on the case to the press.

Khlobystin believes that Bugayev's sense of immunity comes from his work for the Kremlin and his relationship with Vladislav Surkov, the Kremlin's once-omnipotent "gray cardinal" who resigned as deputy prime minister on May 8.

"The man has a criminal consciousness; he believes that the world is built on corruption and mafia-type relationships," Khlobystin said.

"He thinks that the whole world consists of swindlers and that the smarter swindlers deceive the less smart, less lucky swindlers. [He also believes] that [some people] are simply fools, and it is sinful not to make use of them. This kind of criminal consciousness, this kitchen-sink Nietzscheism, is just the same as provincial criminals possess.

Evgenij Kozlov's mixed media work from the second half of the 1980s.

"I think he simply did not expect that Surkov would be sacked just ahead of the exhibition, and came out into the open because he thought that nobody would have the guts to make any claims. But the artists are also from the 1980s, they are the veterans of the scene and are not afraid of him or anything else. The fact that there are four artists, who are old friends, of course, but do not speak to each another that much, [suing Bugayev] means that they express the opinion of many more people in the artistic community."

Bugayev was born in Novorosiisk in 1966. He came to Leningrad in 1980 and met the influential underground musician Sergei Kuryokhin in 1981. He took part in Kuryokhin's Crazy Music Orchestra and, later, Pop Mechanics. He also appeared a few times at concerts by Akvarium's Boris Grebenshchikov and with Kino as a drummer or percussionist.

In Russia, he is best known for his role in Sergei Solovyov's perestroika crime thriller "Assa" (1987), which took its name from the late artist Timur Novikov's gallery and was influenced by the New Artists, featuring underground rock music and alternative art objects.

During the past few years, Bugayev has made a career as a pro-Kremlin activist, which landed him the position of Putin's official advocate.

In July 2010, Bugayev visited Seliger, the summer camp created by the Kremlin for the pro-Putin youth movement Nashi. Reports of his visit cited some of his typically awkward ramblings.

"We were the Komsomol members, the pioneers, whose task was to build power plants," Bugayev said to the Nashi activists at the camp. "Your task is to destroy these plants and build fundamentally new ones."

However, Khlobystin alleged that his visit to Seliger was handsomely paid. For representing the art world at the youth forum, Bugayev was rewarded with funding for his Institute of a New Man, he said.

"I don't know what kind of 'institute' it is," Khlobystin said.

"But Afrika is a 'musician,' about whom [the late Kino leader Viktor] Tsoy said that he had never been a musician with Kino and that he was no musician at all. He is [the kind of] 'artist' who can't draw anything. He is a member of the 'international association of psychiatrists' and so on, while he is a man with an eighth grade education. He is a cynical opportunist, but he has finally outfoxed himself."

In March 2011, Bugayev was the only contemporary artist from among 55 people who signed a letter effectively supporting the prosecution of Mikhail Khodorkovsky, a former oligarch and one of Putin's political opponents.

Widely seen as politicized and without basis, the trial led to protests, petitions and criticism from some of Russia's leading public figures. The Kremlin reacted with a letter from a group of people, including Bugayev, that was called "An Open Letter by the Members of the Public Against Undermining Confidence in the Judicial System of the Russian Federation by the Means of Information."

In February 2012, Bugayev was chosen as one of Putin's 499 official advocates for the 2013 presidential election campaign. In interviews, Bugayev said his role was to promote Putin's ideas while speaking before audiences across Russia. A recent controversy involving the late artist Vladislav Mamyshev-Monroe, however, speculates that he was allegedly involved in secret projects to smear opposition leaders.

"I must stress that this case is not based on politics," Khlobystin said.

"The artists from the 1980s, this entire generation, are apolitical. Afrika is the only activist. But I am sure that his activism has been created out of commercial interest. When the regime changes, he disavows it as soon as possible, he's a totally unprincipled and cynical man.

"He tries to pull us back into those crooked associations that have been left in the past. But I think that it is very important to show everybody else that the times have changed and one can sort out things in an impartial, civil court — that it's purely a property case, a purely domestic case. Because Afrika's position is weak, apparently he will try to move it into the political sphere, asking such questions as 'Who is behind them?' and claiming [that we are agents of] the Orange Revolution, which is absolutely ridiculous. Neither me, nor these four artists who filed the lawsuits have anything to do with politics at all."

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.