U.S. President Barack Obama's decision Wednesday to cancel the planned bilateral meeting with President Vladimir Putin in early September was the right thing to do for many reasons. It also marked much-needed corrections in Obama's "reset" policy toward Russia.

An accumulation of factors went into Obama's decision. The White House press secretary's statement cited "the lack of progress on issues such as missile defense and arms control, trade and commercial relations, global security issues and human rights and civil society in the last 12 months."

Obama elaborated on this in a news conference Friday. "I think we saw more rhetoric on the Russian side that was anti-American, that played into some of the old stereotypes about the Cold War contest between the United States and Russia," Obama said of Putin's return to power last year. "I've encouraged Mr. Putin to think forward as opposed to backwards on those issues, with mixed success."

U.S. officials realized that there would be no deliverables to justify a summit in September. When they last met in June on the margins of the Group of Eight meeting in Northern Ireland, Obama and Putin issued a joint communique that absurdly spoke of " principles of mutual respect."

But the U.S. side should have zero respect for Putin's brutal crackdown against human rights, the worst since the Soviet collapse. Despite the complaint from Putin's foreign policy adviser, Yury Ushakov, that the U.S. "is still not ready to build relations with Russia on an equal basis," the U.S. and Russia, in fact, are not equals.

The G8 communique also spoke of "genuine respect for each other's interests." But Obama should have no respect for Putin's demonization of the U.S. or for his support of Bashar Assad, Syria's murderous leader,.

We are on diametrically opposite sides on Syria with Putin having aligned Russia with Hamas and Iran while supporting and arming Assad. The latest examples of the unprecedented assault on human rights under Putin include the posthumous conviction of lawyer Sergei Magnitsky, the absurd five-year sentence handed down to opposition leader Alexei Navalny, and the hundreds of nongovernmental organizations that have been raided for not complying with the requirement to adopt the title of "foreign agent." In addition, those linked to the Bolotnoye protest more than a year ago still face trial, many while sitting in prison; Russian security services blatantly monitor and follow activists and opposition figures; and the Kremlin has sponsored an anti-gay campaign that has generated outrage in the West.

Even if some of these actions play well among the Russian population, they contradict the interests and values of the U.S., and Obama could no longer look the other way. The Edward Snowden case was the final straw for the White House, but not the main consideration, nor should it have been. As Putin said, he didn't invite Snowden to Moscow.

Obama's reference during his news conference to Putin's anti-Americanism hit at a central problem. On a regular basis, Putin trashes the U.S. and describes it as a threat. Recall his blast against the West in his speech in Munich in 2007 and then his comparison a few months later of the U.S. to the Third Reich, or his attacks against former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, whom he blamed for stirring up the protests in Russia in December 2011. He evinces disdain for his current U.S. counterpart and disrespect for the U.S. in general. Granting Snowden asylum a month before Obama was to come to Moscow to meet with Putin was the latest manifestation of Putin's anti-U.S. campaign.

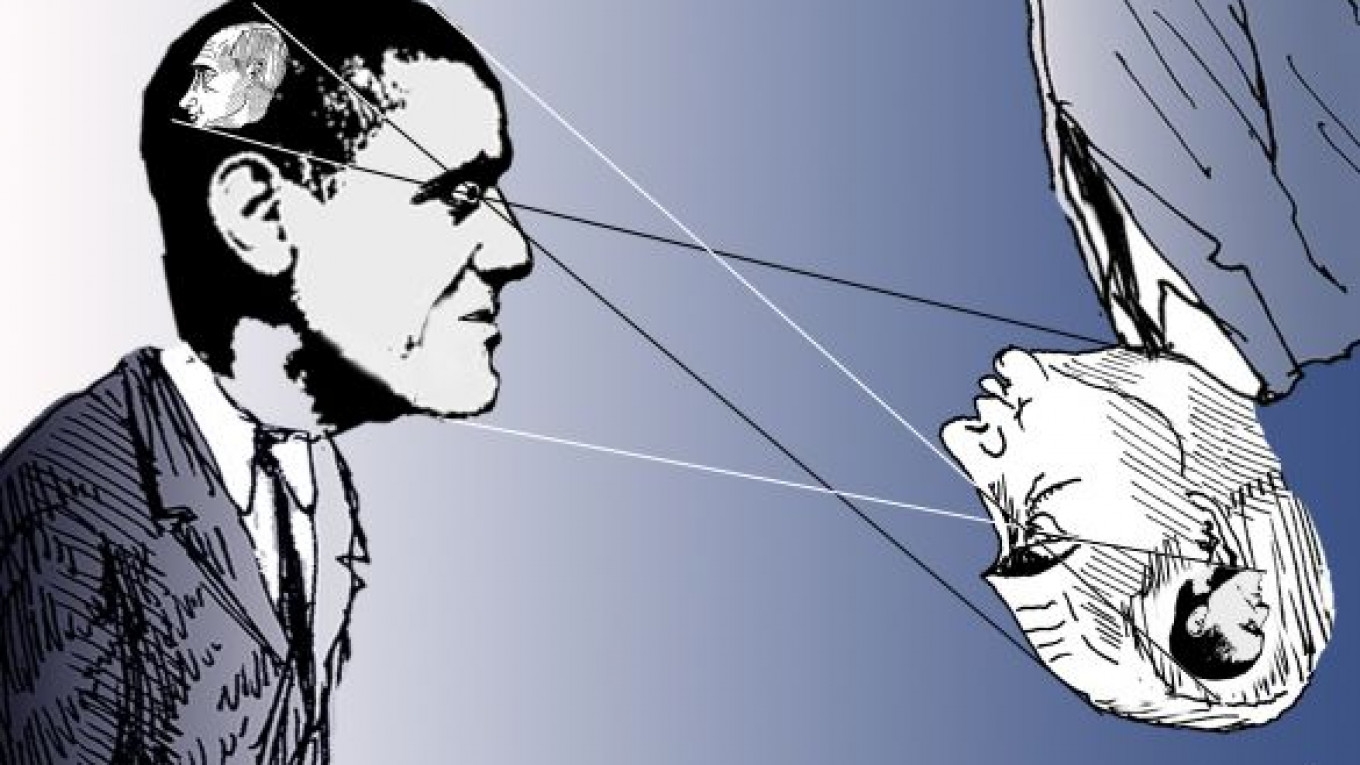

This typifies a schizophrenia Putin has toward the U.S. On one hand, he demonizes the U.S. and cites it as a threat to try to justify his way of ruling the country and consolidating power, starting with the takeover of television networks in his early presidential days, to his abuse of the legal system to go after leading opposition figures such as Mikhail Khodorokovsky in 2003 and Navalny. In overseeing a corrupt regime, Putin seeks to instill a sense of fear among those who might challenge his grip on power while manufacturing threats from the West to justify whatever he needs to do to preserve that power. According to a new Levada Center poll, disappointment in Putin among Russians is on the rise, and the economy is facing serious challenges. As a result, we can expect the U.S. to become even more of a punching bag.

But at the same time, Putin wants the legitimacy and acceptance of the West to accompany his tough-guy image. Standing together with his G8 colleagues, whom he is scheduled to host next year, or sharing a stage with the U.S. president are, in his mind, ways to legitimize his rein both internationally and at home.

Last week, finally, Obama broke his painfully long silence over Putin's brazen behavior and rhetoric, essentially saying that enough was enough. In canceling his meeting with Putin, Obama also abandoned two central tenets of his reset policy: his happy talk of a "win-win" approach to relations and his public and repeated rejection of linkage. Putin's zero-sum mindset simply doesn't have room for thinking in mutually beneficial ways.

Until last week, the U.S. administration had made clear that Putin's human rights crackdown and anti-Americanism would not affect the broader U.S.-Russian relationship. Such an approach irresponsibly sent Putin a green light to engage in egregious abuses without having to worry about paying any price in bilateral ties. Last week, however, in a long overdue policy correction, Obama changed the green light to at least a yellow one. This sent an important signal both to Putin and to Russians that there indeed are costs to bad behavior.

David J. Kramer is president of Freedom House in Washington.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.