A major business deal in which Rosneft would deliver Russian oil to China for the next 25 years was announced at last week's St. Petersburg International Economic Forum. President Vladimir Putin set the value of the deal at $60 billion, while Rosneft CEO Igor Sechin put it at $270 billion, apparently multiplying the $100-per-barrel figure by the total number of barrels to be delivered to China under the agreement. But the real question is: How advantageous is this contract for Russia over the long-term?

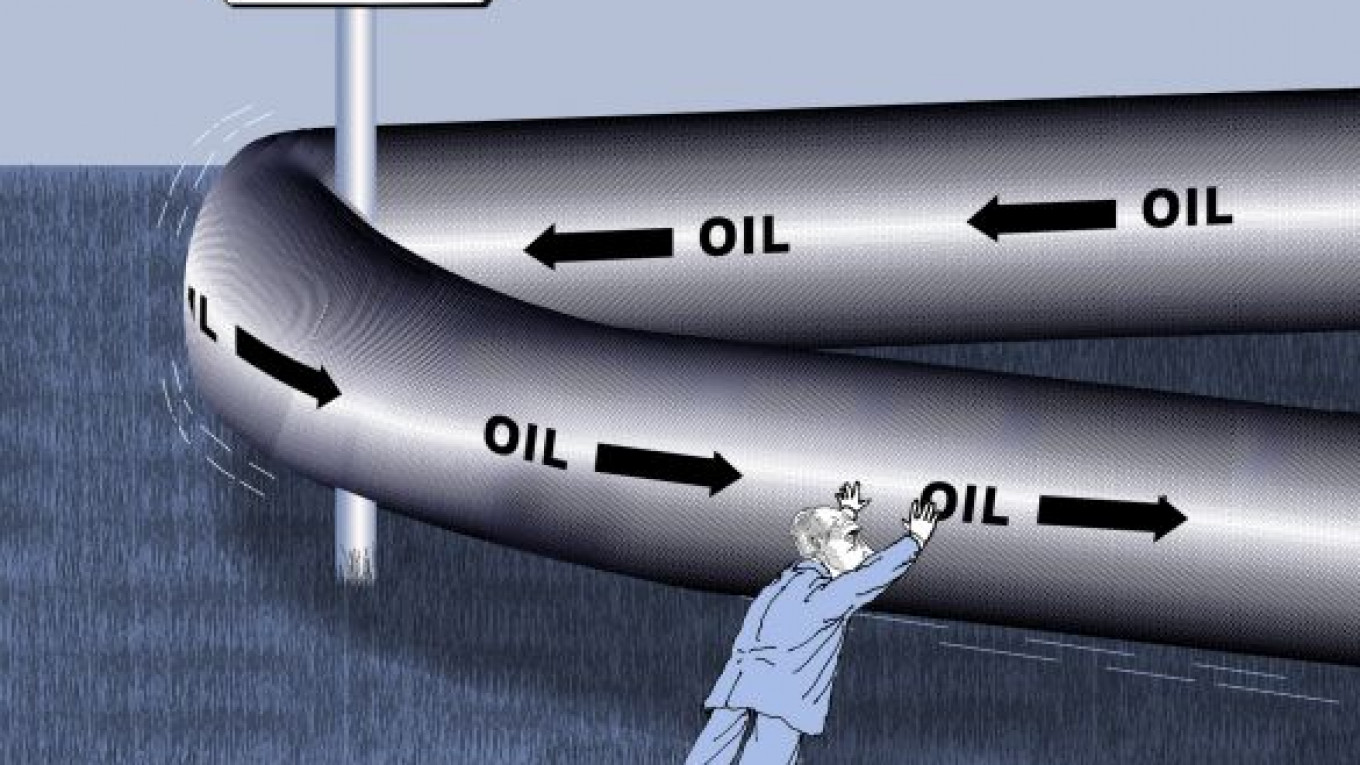

Rosneft has now become a powerful player in the energy market, acting as the de facto and autocratic "steward" of all oil in the country's eastern regions. At the same time, Rosneft is fulfilling the state's strategic goal of diversifying oil deliveries. Although Russian leaders and Rosneft managers have made assurances that oil deliveries to China will in no way affect deliveries to the West, Moscow is, in fact, playing the "Chinese energy card" against the West, and primarily against Europe.

Rosneft will help the Kremlin finally realize its dream of selling lots of oil to China and reduce its dependence on energy exports to the West.

The Kremlin is infatuated with the idea of finally being able to reduce the country's dependence on exports to the West. In 2009, it released a document titled "Russia's Energy Strategy Through 2030" that contained the following passage: "The share of liquid hydrocarbon deliveries to Europe should steadily decrease in favor of deliveries to the east. The share of the latter should increase from 6 percent to from 20 percent to 25 percent for oil and from 0 percent to 20 percent for gas. These deliveries should contribute to the development of Russia's eastern territories, reducing the number of people leaving that region."

Rosneft is doing exactly what Yukos wanted to do more than 10 years ago. Before Yukos was swallowed up by Baikal Finance Group — that is, Rosneft — in 2004, former Yukos CEO Mikhail Khodorkovsky was the first person to initiate serious talks with Beijing in the late 1990s regarding the export of oil through new pipelines to China.

The deal with China puts Rosneft in a position to fulfill its chosen mission to become a major global oil corporation. Rosneft used two large loans from China to help acquire Yukos after the company's auction in 2004. Now Rosneft will use part of the anticipated profits from oil shipments to China to pay down its enormous debt from the acquisition of TNK-BP in March.

The current contract calls for Russia to supply China with 365 million tons of oil over 25 years. But there is a possibility that the Russian budget, in the form of state-controlled Rosneft, will not earn as much money from this deal as today's jubilant news releases suggest. Russian oil will be delivered through the Eastern Siberia–Pacific Ocean pipeline, which was essentially built with Chinese money — a $25 billion loan that the Chinese Development Bank extended to Rosneft and Transneft, the state-controlled pipeline company. When the decree to build the pipeline was signed in 2004, Putin hailed it "breaking a window through to the East." Unofficially, the pipeline was meant to apply pressure on Europe. Construction of the pipeline to China has given impetus to the development of oil deposits in Eastern Siberia, the majority of which are now owned by Rosneft, that had remained untapped for lack of a client in the region.

What's more, China recently received oil from Russia, including deliveries made by a different pipeline built in the early 2000s. That oil was purchased at far below market price — estimated to be about $60 per barrel. Rosneft will now be hard-pressed to fulfill its obligations under the contract signed at the St. Petersburg forum. It must find money to increase the carrying capacity of the pipeline to China as well as enough oil to fill the pipeline, pitting Rosneft in a dispute with Transneft over who will pay those costs. It is very possible that the pipeline expansion will be accomplished at the expense of other oil companies, meaning that Russian consumers will end up footing the bill. To fulfill its export commitments to China, Rosneft has already stopped fulfilling its contractual oil supply obligations to the Omsk Oil Refinery that produces gasoline for Russia's domestic market.

China is in a very strong negotiating position and can obtain significant oil concessions from Russia. On one hand, Rosneft has already exceeded its strategic goals, exporting 15 million tons of oil to China of the more than 18 million tons it exported to the Asian-Pacific region in 2011. At the same time, however, China has been very careful to diversify its oil imports, buying only 10 percent of its oil from Russia, while 90 percent of its imports are from Africa, the Middle East and South America.

Since Russia entered China's oil market far too late, it won't be able to become a major player there. Nor will it be able to dictate its own terms. Of course, that does not stop Moscow from playing its "Chinese oil card" in its relations with the West — even if it does so at the cost of lost markets and profits.

Georgy Bovt is a political analyst.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.