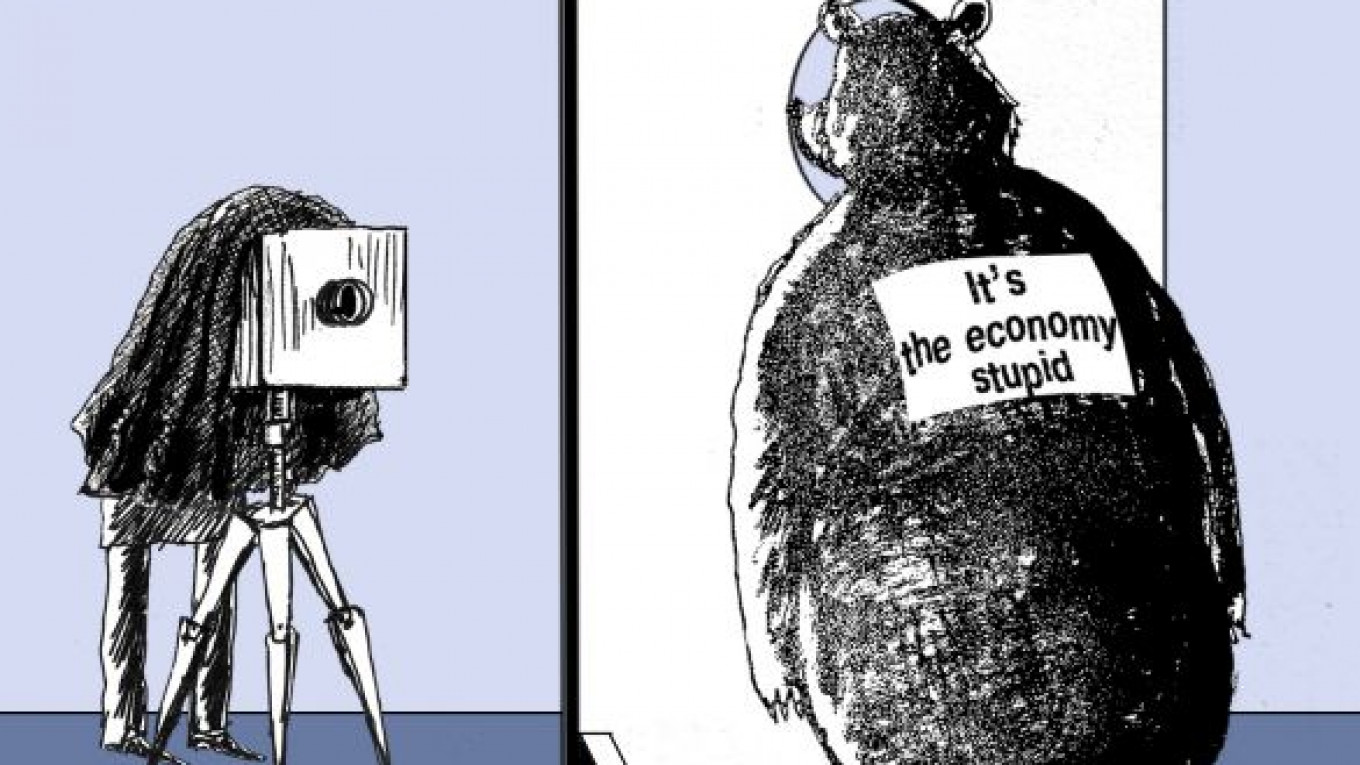

The core of the argument taking place at the top of government right now is about how to boost mid- and long-term economic growth without risking a loss of the current relative stability in the economy and the country. Or, to refine it even more basically, what measures can be agreed to today which will best ensure public support for the Kremlin's preferences during the State Duma and presidential elections in 2016 and 2018? In this regard, Russia is no different from most other countries. Political leaders everywhere are constantly balancing short-term populist measures with longer-term strategy. Most leaders probably have the slogan that U.S. presidential candidate Bill Clinton adopted for his 1992 campaign — "It's the economy stupid" — hanging on their office walls.

To be sure, economists have been talking for many years about the need for radical reforms and warning of the dire consequences for both the economy and social stability if those reforms are not implemented. But it is only relatively recently that the message of "something needs to be done" appears to have reached the top of the country's to-do list. This maybe a legacy of the pre-election protests or quite possibly a realization that the price of oil is now living on borrowed time. Shale oil and gas is no longer a vague threat to traditional oil and gas producers. It is now a very stark reality. If it weren't for the ongoing conflict in Syria and the street protests in Istanbul, the price of Brent and Urals would surely be closer to $90 per barrel today than sitting above $100 per barrel. At $90, Russia's flaws become more obvious and the future more uncertain.

It is clear why raising its credit rating has become a top priority for Russia. Above all, it would make it easier and cheaper to access debt markets.

So while former Finance Minister Alexei Kudrin and others continue to call for the government to move away from short-term populist measures in favor of real budget and policy reforms, what can we actually expect from the current debate in government? Unfortunately, the only actions already agreed offer no basis for raising expectations. Instead of agreeing on measures to slash budget spending in nonproductive areas, such as defense procurement and subsidies to state enterprises, the government is still focusing its efforts on "investment populism." Instead, it should focus on investing more in education, infrastructure and support for entrepreneurs.

Earlier this year, the Kremlin awarded a $500,000 contract to investment bank Goldman Sachs for the purpose of boosting Russia's investment image. In May, Moscow signed a contract with another heavyweight Wall Street bank, JPMorgan Chase, with the more specific goal of helping the country gain a credit rating of A from the major debt rating agencies by 2016. Of course, rating agencies are no more likely to succumb to a slick advertising campaign than are investors, either foreign or domestic.

Russia needs a big increase in investment spending directed at areas of the economy that can boost average annual economic growth and sustain it close to the targeted five percentage points. It doesn't much matter whether that increase comes as a result of restructuring federal budget spending or a reversal of domestic capital flight or an increase in foreign direct investment — that is, real equity investment and not just round-tripping Russian cash via offshore centers such as Cyprus — or from easier access and confidence to borrow by businesses. What is most important is that the country sees a real increase in investment spending.

It is clear why the government would like a higher rating. If the rating of sovereign debt was to be raised to the level of A, then it would both be easier and cheaper for the Finance Ministry to access debt markets. Russia's biggest corporations would also benefit as many of them have a rating that is linked to that of the state. Today Russia sovereign risk is rated at BBB by both Fitch and S&P. That rating is three levels below single A and two above minimum investment grade. Moody's are marginally better with a Baa1 rating, which is three places above the minimum. In practical terms, that means Russia pays more to borrow than would be the case if the ratings were higher.

The government is about to embark on an investor roadshow aimed at attracting support for a forthcoming $7 billion bond issue. At the current yield of Russia long-term debt, the annual interest cost of borrowing that money will be about $250 million. If Russia debt were to be rated similarly to that of the hugely indebted U.S., the annual interest cost would be $150 million. If rated similarly to AAA-rated German debt, the interest cost would be closer to $110 million annually. So there are good practical reasons why the government is frustrated at the low credit rating. It does not reflect the country's relatively better debt position to that of the U.S. or Germany. It also leads to higher annual debt service costs and sends a negative signal to potential investors.

But that is almost a side issue now because the rating agencies have made it very clear that they are now completely focused on the same issues as are investors — that is, what actions the government is taking to lessen commodity risk and to boost sustainable growth rates. There was a time when the criteria for a sovereign credit rating was simply the willingness and ability to repay debt. If that measure were applied in isolation today, Russia would absolutely be one of the world's few AAA-rated borrowers. Instead, Moody's, Fitch and S&P want to know the answers to the same questions being asked by investors: How will the government cut oil risk in the budget? What practical measures will be undertaken to attract a higher volume of investment into the country and to retain domestic capital? How will the economy be made more competitive? The list is a familiar one.

Better public relations may help. Investors already committed to Russia have been regularly frustrated at widely disseminated negative perceptions of Russia risk and have been pleading for years for a more realistic message about the country. The popular view of high Russia risk is surely at odds with an economy that has grown from about $200 billion in 1999 to about $2 trillion this year (based on purchasing power parity), and an economy that today boasts the world's fifth-largest consumer market and the highest spending power per capita amongst all emerging economies.

From 2004 to 2008, the economy was growing and the stock market was the best performing in the world. During this period, an effective PR campaign would have worked well and created a better risk perception legacy. But that time is long gone, unfortunately. Today, the rating agencies, foreign investors and domestic businesses want real actions such as budget and policy reforms. If we do see progress in these areas over the next few years, this will be something worth shouting about to the international business community. If these changes are not forthcoming, however, a PR campaign will only serve to highlight the deficiencies in the story and confirm the rationale for the relatively poor risk assessment.

We can only hope that somewhere on a Kremlin office wall Bill Clinton's campaign slogan has a prominent position. Perhaps JP Morgan can offer a gold-plated, framed print.

Chris Weafer is senior partner with Macro Advisory, a consultancy advising macro hedge funds and foreign companies looking at investment opportunities in Russia.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.