The bill protecting "believers' feelings," which rights activists and analysts have called a "step back" for Russia, a legal "Pandora's Box" and a return to the Dark Ages, looks set to take effect in July after sailing through the State Duma with a unanimous vote on Wednesday.

The so-called "blasphemy law," which stipulates criminal prosecution for any abuse of religious feelings, has already provoked a chorus of criticism, with many warning that it will be applied selectively, increase religious intolerance and violate the Constitution's recognition of Russia as a secular state.

In a preview of how the law may be applied if it gets final approval from the Federation Council and President Vladimir Putin, a Muslim organization on May 27 called for "legal liability" to be imposed on a children's book publisher whose illustration it said offended Muslims. The illustration in question was a picture of a crocodile holding what Islam.ru said resembled a torn-out page from the Koran.

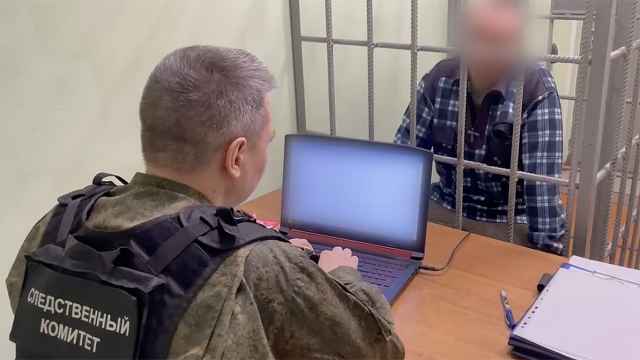

The new legislation came about after Orthodox believers cried foul over the female punk band Pussy Riot's controversial performance in Moscow's Christ the Savior Cathedral last year, a performance which saw three young women repeatedly denounced during trial for "offending religious believers" and sentenced to two-years behind bars for "hooliganism motivated by religious hatred."

Conservative-leaning segments of Russian society have said the new law, initiated last September by deputies of the State Duma's four factions, would serve to protect the Russian Orthodox Church — whose image observers say has worsened significantly in the last several years — from actions similar to those of Pussy Riot.

But human rights activists say the legislation is one of many repressive bills drafted by the State Duma last year amid a burst of opposition activity. They say the legislation is aimed at blunting criticism of the Kremlin and the Russian Orthodox Church, a crucial part of the president's patriotism program to rally Russians together.

Experts fear that other religious groups will be excluded from the law's application and that dividing the rights of believers from those of individuals will spark violence and increase repression of minority groups.

"This bill could open a judicial Pandora's Box of potential abuse and arbitrary rulings, and cases could be brought against members of religious minorities, atheists, and agnostics, as well as against activists in social and political movements or members of alternative ways of life alleged to have offended Moscow Patriarchate structures," said Catherine Cosman, a senior policy analyst with the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom, an independent body within the U.S. government that monitors violations of religious freedom abroad.

Overkill?

One of the bill's authors, Liberal Democratic Party member and head of the Duma's Social and Religious Organizations Committee Yaroslav Nilov, called 2012 "a year of vivid blasphemous challenges to society," making the bill a high priority for Russian society.

Cosman, however, said blasphemy should not be controlled by law at all.

"Laws are meant to protect individuals, not beliefs," she said. "The Russian Constitution recognizes the separation of religion from the state and the right to believe — or not to believe — in religion. I do not see how this law is compatible with such Russian constitutional principles."

Although the bill was ready for consideration last fall, the Duma was told to improve its ambiguous wording and delete from it those norms that were already regulated by other laws.

After six months of wrangling, the Duma's Social and Religious Organizations Committee, the Kremlin human rights council and the Public Chamber prepared a number of amendments to the original bill, though observers said the main drawbacks remained.

The new draft of the bill lowers the maximum prison sentence for "offending the feelings of religious believers" to three years, while the maximum fine stays at 500,000 rubles ($16,000).

In addition, prosecutors have to prove that the offenders' actions were premeditated. The bill would also punish "desecration of religious literature, marks, labels and symbols."

Olga Sibiryova, a religious issues expert at the Sova think tank, said that even though the new bill was better than the previous one, it still contained articles similar to those the current legislation has.

"There is already a law that guarantees human dignity — It can be applied to religious feelings as well," she said. "The [new] bill also stipulates punishment for vandalism in sacred places, while there is already a law punishing acts of vandalism committed anywhere."

Representatives of several religious organizations interviewed by The Moscow Times said that there was no need for a new law and that the current laws were enough to ensure the rights of religious people.

"The needs of believers don't differ from the needs of any other people," said Dmitry Blagochinkov, pastor of the Moscow Bible Church. "So, if someone breaks a crucifix it is vandalism; if someone offends a pastor, it is hooliganism."

Sibiryova agreed. "Putting religious feelings in a separate category is unreasonable. What makes religious feelings more important than any other feelings? This very question makes the situation in society potentially conflictive," she said.

Abdelmalek Hazrat, from the Muslim organization Mercy, agreed that all Russian citizens, regardless of their religious beliefs, should be guaranteed their rights.

Complicating things further, observers and members of religious organizations say that the term "feelings" is far too vague, and that law enforcement authorities and judges would interpret the term differently in different situations and possibly use the bill to protect powerful interests.

For instance, Sibiryova said, the bill is likely to allow any criticism of the Russian Orthodox Church to be considered blasphemy.

Alexei Voskresensky, secretary of the church council at Word of Life, an evangelical Christian church, said the term "religious feelings" was unclear and open to different interpretations. "It is very difficult to define a provision of law for a thing that doesn't physically exist," he said.

Boruch Gorin, a spokesman for the Jewish Community Center, said he was more concerned not with the bill itself but with how it would be implemented. According to him, religious organizations should not use the law at all to avoid increasing antagonism toward religion in society.

"There isn't even a high-quality expert assessment to give a precise definition of xenophobia. So how can we define what feelings are?" Gorin said.

Cosman, of the USCIRF, said the only way to avoid the pitfalls of such vague terminology was to limit prosecution of abuse of "believers' feelings" to threats of imminent violence or actual violence against a specific individual.

Warnings of Intolerance

While Russia would not be the first country to have a blasphemy law if it is approved, many countries are freezing such laws or deleting them from the books altogether.

Denmark has a law under which a person could face time in prison for insulting or ridiculing any religion, but it has not been used since 1938. Similarly, the U.K. scrapped a blasphemy law in 2008 at the initiative of then-Prime Minister Gordon Brown's Labour Party. Sweden discarded its blasphemy law in 1949 and later replaced it with a religious freedom law.

According to Cosman, blasphemy laws are incompatible with international human rights standards, since they protect beliefs over individuals and thereby empower governments and majorities to enforce particular religious views against individuals and minorities.

"There is catastrophe waiting to happen in this bill. Its implementation will be like a witch hunt in the Middle Ages, and every punishment will be seen as a convergence of the church and the state and an attempt to strangle freedom of belief," Gorin said, adding that relations between different religions in Russia's multi-ethnic society could also be damaged.

Although the legislation says that offending the feelings of any religious group will be punished, Sibiryova said it was unlikely that the law would be used to defend the rights of small groups like Jehovah's Witnesses.

Some experts cite Russia's laws against extremism as an example of how the blasphemy bill could be selectively applied to only certain groups.

According to the International Religious Freedom Report for 2012 issued by the U.S. State Department in May, the Russian government "targeted members of minority religious groups through the use of extremism charges to ban religious materials and restrict groups' right to assemble."

In one such example, a Novosibirsk court convicted two imams for spreading religious literature that the court deemed extremist. The Memorial human rights group said the prosecution was illegal.

The government said on May 28 that its legislation commission had approved for consideration by the Duma a bill that would stipulate larger fines and longer prison terms for "destructive activity by religious organizations."

Observers warned that the consequences of both these bills could be dangerous for society.

"The blasphemy bill, whose supporters often justify it by saying it is necessary to promote religious harmony, in fact is likely to have the opposite effect, exacerbating religious intolerance, discrimination and violence," Cosman said.

Contact the author at e.kravtsova@imedia.ru

Related articles:

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.