Any discussion about the Russian work ethic inevitably ends up focusing on the Soviet Union, which did more than any other period in the country's history to corrupt work habits. Although much has improved since the Soviet collapse, Russians haven't been able to shake off some of the worst legacies of the Soviet work ethic.

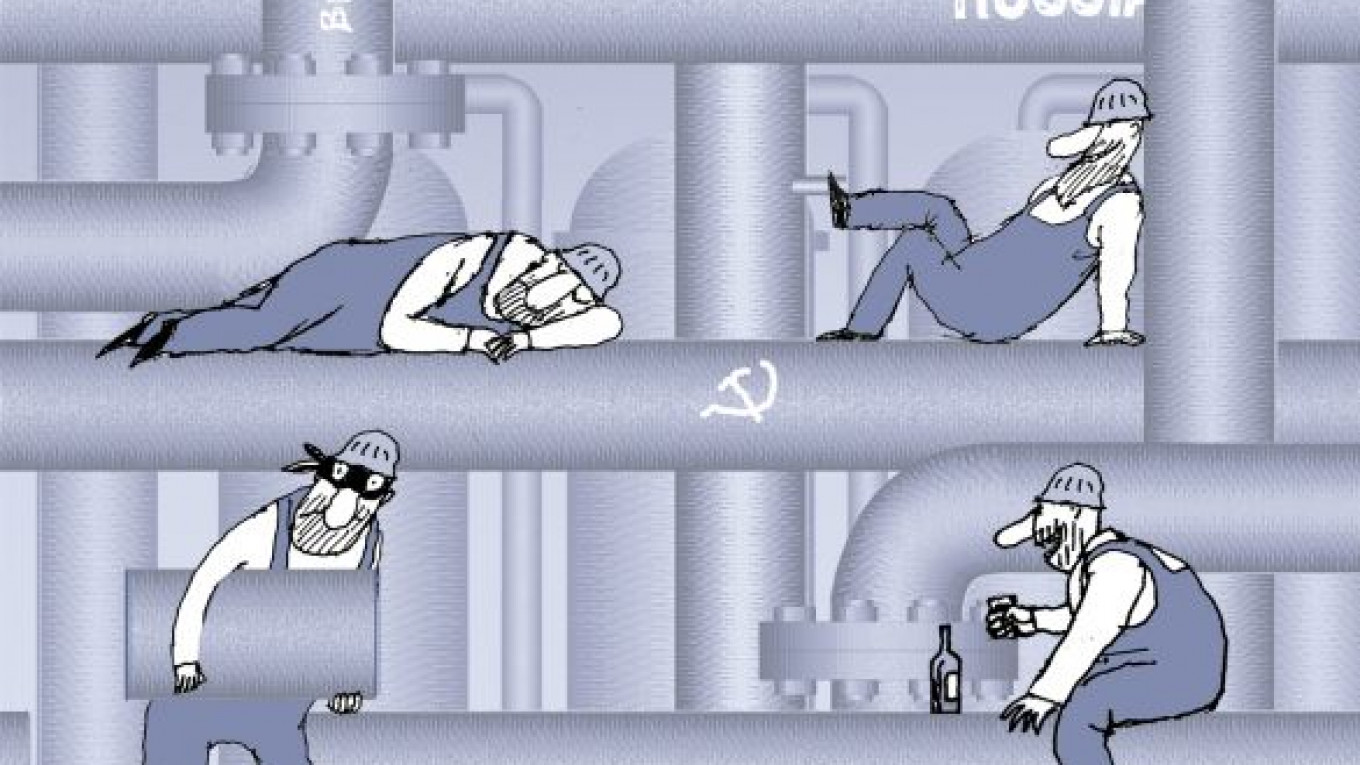

Here are the top seven components of the poor Soviet work ethic:

1. Pofigizm. Combining apathy, indifference and fatalism, pofigizm can be translated as "I don't give a damn." To be sure, pofigizm existed as a national phenomenon long before the Soviet Union. Take, for example, the centuries-old Russian folklore hero Yemelya or the 19th-century literary character Ilya Oblomov, both of whom were quintessential national symbols of pofigizm. Yet nothing did more than the Soviet Union's systemic political and economic stagnation, particularly in the Brezhnev years, to exacerbate the key elements of pofigizm — inertia, hopelessness and disillusionment — in the workplace.

Russian's poor work ethic has more to do with the country's distorted political and economic environment and less to do with a distorted "Russian mentality."

Today, pofigizm helps explain, for example, why several years ago construction workers putting up a billboard in central Moscow didn't bother investigating what was underneath the ground and drove a pillar directly into a metro car beneath it. "Why bother with all of that tedious surveying work?" they (and presumably their management as well) said. "Maybe we will get lucky and not hit anything." This type of pofigizm, combined with its close relative avos (on the off-chance), is still encountered quite often in the Russian workplace.

2. Irresponsibility. Since there was no private ownership in the Soviet Union, factories and other workplaces formally belonged to everyone, which, in reality, meant that they belonged to nobody. As a result, workers felt little personal responsibility for their work or the end product. And even if they did care, there was little in their power they could do to improve the quality of their work because of the poor quality of component parts — or because these parts were chronically unavailable to begin with. The lack of responsibility, combined with pofigizm, was a driving force behind the Soviet Union's systemic low productivity, inefficiency and low-quality goods.

3. "Equality in Poverty." The Communist Party tried to use the principle of "poor but equal" as a palliative and opiate to the masses to extinguish jealousy and "class-based antagonism." But the only thing it extinguished was initiative, innovation and motivation in the workplace.

4. Mukhlyozh. Encompassing swindling, padding production numbers and other measures to deceive the bosses, the bosses' bosses and regulatory authorities, mukhlyozh — and not hard, honest work — became the most valuable and useful "business skill" during the Soviet Union. It is not hard to fathom how much 70 years of ubiquitous mukhlyozh destroyed the Soviet work ethic.

Today, mukhlyozh and more sophisticated forms of corruption are still considered an important "business skill" to get ahead. To make matters worse, Russia's weak rule of law only serves as a catalyst for even more mukhlyozh and corruption. Not surprisingly, in a Levada Center poll published this week, 73 percent of Russians think it is impossible to become wealthy in Russia through honest means.

5. Lack of ambition. In the West, an ambitious person — one with drive and initiative — is highly regarded in society and often rewarded by employers. But during the Soviet period, an ambitsiozny chelovek (ambitious person) was an "individualist" or "careerist," which were pejorative terms according to the collectivist Soviet ideology, and someone who didn't fit into the workplace.

Even today, the negative Soviet connotation of "ambition" remains. To most Russians, an "ambitious person" is vain, arrogant and pretentious and someone who is willing to do anything — including using deceit, guile and even betrayal — to get ahead of others at work.

6. Lack of a competitive work environment. Although competition permeates most workplaces in the West and is a powerful engine that drives innovation and progress in a capitalist system, Soviet ideology demonized the Western concept of competition, claiming that it was cruel, cutthroat and inhumane. Western competition, according to Communist propaganda, destroyed the work ethic in the West by pitting one employee against the other in a vicious and nefarious dog-eat-dog world. In contrast, Soviet communism provided lifetime guaranteed employment for everyone, which, Soviets were told, led to social harmony, high job satisfaction and high productivity in the workplace.

Notably, many Russians whom I interviewed for a five-year study that I carried out on the Russian work ethic still have a negative association with competition. During my research, I often encountered Russians who were unhappy with their dead-end, low-paying and generally uninspiring jobs. I suggested that they go on 10 or 15 interviews with better, Western-oriented companies that they would be qualified to work for. The first reaction I often heard was: "Job interviews? No way! They are so degrading!" This was often followed by: "And besides, what if they reject me?"

7. Blat. Although several of the components of the poor Soviet work ethic have been mitigated by the end of the Communist ideology and the emergence of a profit-driven private sector over the past 20 years, blat, or connections, is the one feature of the workplace, in addition to corruption, that has actually gotten worse in post-Soviet Russia. In every society, people use blat to help them find work, but this phenomenon is much more pervasive in Russia than in most Western countries.

Even President Vladimir Putin and Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev have spoken openly about blat, admitting that the system of finding work and receiving promotions is far too closed for a country that wants to develop a modern, Western economy. When blat and nepotism takes precedence over a merit-based system, this can have a disastrous impact on the Russian work ethic.

But it is clear that the negative aspects of the Russian work ethic have much more to do with the country's distorted political and economic environment and less to do with a distorted "Russian mentality" or inherent national traits. The best proof of this is to look at Russian emigres who, in general, do quite well in the U.S. and Europe.

Their work habits dramatically improve once they encounter a healthy political, economic and legal environment in the West and find themselves in a workplace that inspires and rewards personal initiative, drive and motivation. In many cases, the former "poor Russian work ethic" quickly turns into a "Protestant work ethic" once they are paid better and treated with more respect, once they are provided with pensions and subsidized health insurance, once the law protects their rights and their private property, once corruption in the workplace is minimized and once there are more opportunities to build a career and advance within a company based on merit.

So where does the Russian work ethic stand now?

Although several elements of the poor Soviet work ethic still remain in the Russian workplace, there are several signs of progress. First, a relatively large private business sector has emerged over the past 20 years. Second, free-market competition and the profit motive have forced these companies to increase innovation, productivity, motivation and efficiency just to stay afloat, much less prosper. Third, more Russians are studying abroad in MBA programs and bringing back to Russian companies valuable Western management techniques and skills.

And last but not least, over the past 12 years Russians have become closely familiar with a leader who has set a new standard for working hard — a person who truly does work like a "slave in the galley."

Now if only Putin could do as much to curb mukhlyozh and corruption as he has to counter Russian pofigizm, not only would the Russian work ethic improve, but the whole economy and investment climate would benefit as well.

Michael Bohm is opinion page editor of The Moscow Times and author of "The Russian Specific: An Analysis of the Russian Work Ethiс" (A. Golod, 2007).

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.