Sergei Prikhodko, a foreign policy adviser to Russia's leaders for more than 15 years, was appointed a deputy prime minister and government chief of staff last week, replacing Vladislav Surkov. President Vladimir Putin did not bother looking for someone outside of the government and did not delegate the post to any of the members of his administration. He simply looked at the men who had been sitting for years on his personal "reserve bench." As it turns out, all the talk of creating a presidential "talent pool" of young and promising politicians and managers who could be called in to fill key government positions was ignored.

Prikhodko is the quintessential technocrat. Putin, who has a particular fondness for these types, previously appointed technocrats Mikhail Fradkov and Viktor Zubkov to the prime minister spot for the same reasons. Above all, Putin values their loyalty and their ability to avoid drawing the attention of the media and public opinion. In contrast to Surkov, Prikhodko knows his role and will never conduct an independent political game of intrigue.

In contrast to Surkov, Sergei Prikhodko knows his role and will never conduct an independent political game of intrigue.

Many journalists have positive memories of the way Prikhodko used to hold frequent foreign policy briefings for the media. He has an easygoing manner and even a sense of humor at times. But, as is the case with all technocrats, journalists could rarely glean anything substantial from his briefings.

Political analysts close to the Kremlin were full of praise for Prikhodko's appointment, claiming that it was a sign of "Putin's faith in Medvedev's government." After all, they argued, Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev managed to have "one of his own" appointed to this post.

But these comments strike me as wishful thinking. First, Prikhodko can hardly be considered "Medvedev's man." Second, his appointment as chief of staff is unlikely to have even the slightest effect on the fate of the current government. After all, the fate of Medvedev's government is not determined by his ability to consolidate a team of loyalists around himself but is entirely dependent on Putin's will. When Putin decides he no longer wants this government, he will dissolve it along with all of "Medvedev's people," including Prikhodko.

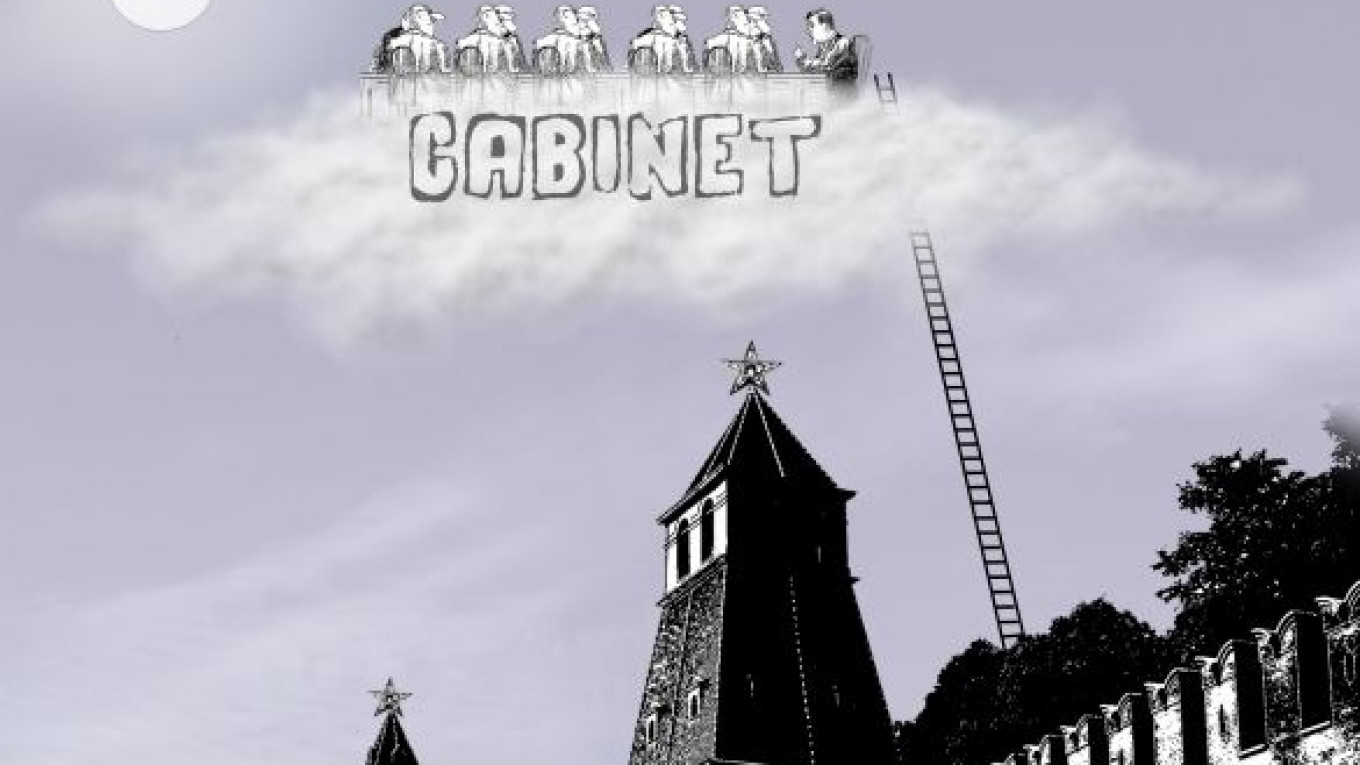

The first year of the Cabinet's work was summed up recently, and the result was hardly inspiring. It couldn't claim a single outstanding achievement — not even a bill that was introduced and adopted at the initiative of the government. Putin has not hidden his displeasure at the way the Cabinet has failed to implement the so-called social decrees he issued one year ago. Although Cabinet members themselves do not dare to oppose Putin, outside experts argue that it would be impossible to implement Putin's costly populist decrees in a stagnant economy.

The Kremlin, however, ignores such reasoning, just as it ignores evaluations from independent experts that simply issuing decrees to raise pensions and salaries of state employees will not spur the economy. They argue that economic development depends upon fundamental reforms to the political and economic institutions that have remained dependent on the Kremlin. In addition, the Kremlin must initiate a real battle against corruption.

In the end, every practical step required for stimulating the economy requires basic political changes. But even Medvedev looks on passively as Putin dismantles nearly all of the "liberal legacies" of his presidency piece by piece. The only element that remain is his initiative to institute zero tolerance for drivers with even the most minor levels of alcohol in their blood. (His attempt at reforming daylight savings time doesn't count because it failed.)

Despite direct orders from Putin, the government is dragging its feet in reforming the pension system. It understands that pension reform is a no-win situation. Given Russia's economic problems and its aging population, it is practically impossible to create a pension system that would make everybody happy. Putin has already said the retirement age cannot be raised and is shifting the burden onto the government to figure out how to pay pensions and to whom. What's more, with a worsening global economy and economic stagnation at home, the government might have to implement a number of other unpopular measures as well.

Putin can thereby comfortably remain above the fray, occasionally criticizing the government for failing to fulfill its duties, while it is clear to most that the Kremlin calls all the shots and should take responsibility for the government's failures. Putin will dissolve the government only when it begins to negatively influence his own popularity. After all, people could argue he was the one who appointed the government, so why does he tolerate its poor performance and incompetence?

But before Putin dissolves the Cabinet, he must first appoint a new, servile technocrat as prime minister, one that will be just as low-profile and loyal as Medvedev and Prikhodko.

Georgy Bovt is a political analyst.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.