The Magnitsky blacklist, released by the U.S. on Friday, is laudable for its attempts to punish officials responsible for the prosecution and death of Sergei Magnitsky and their alleged participation in a $230 million corruption scheme connected with it.

But the effect of the blacklist and the accompanying U.S. Magnitsky Act on an anti-corruption campaign in Russia may be limited. Most of the Russian officials included on the blacklist were probably never seriously interested in investing into the American economy nor in living in the U.S. Moreover, the way that the Magnitsky Act was adopted opens the door for the argument that U.S. authorities are meddling in Russian domestic affairs and unfairly trying to punish people who never were found guilty by any court.

The U.S. and other Western governments should consider using other measures that might be more effective and at the same time provoke a more favorable reaction in Russian society.

Here's an example: Recently, President Vladimir Putin banned Russian officials and their direct family members from having foreign bank accounts and holding stocks and bonds overseas. They are also prohibited from acquiring dual citizenship or even long-term residence permits. While this measure might be in large part symbolic, Western governments should act as if they were taking the development seriously and express an interest in assisting the Kremlin in tracking lawmakers, high-ranking officials in federal and local governments, and top managers in state-controlled corporations.

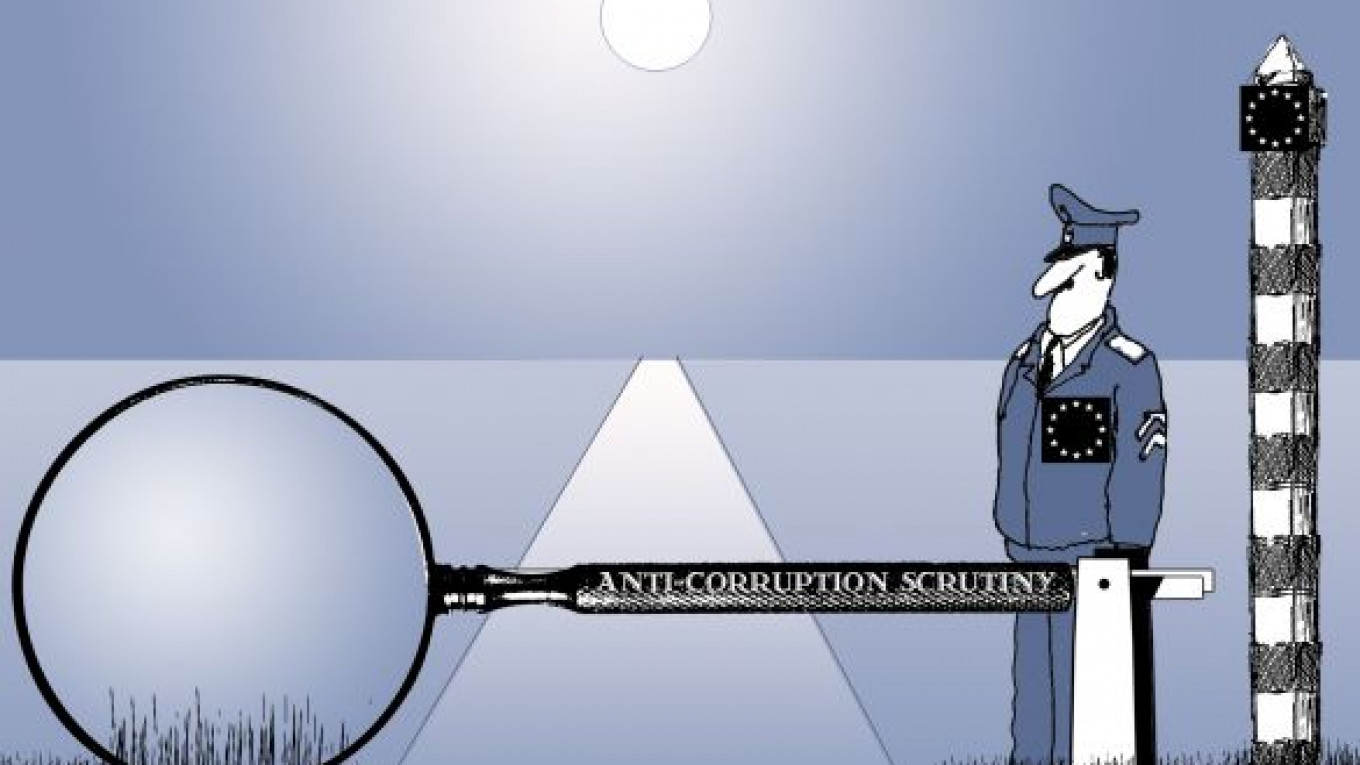

Here's a mechanism that would allow this proposal to work: These days, Russian officials are trying hard to foster a deal on visa-free travel between Russia and the European Union. The stumbling block here is the problem of so-called "service passport" holders. The number of such passports issued to Russian officials exceeds 180,000, and both sides currently are close to reaching an agreement to allow 15,000 of the most privileged of them to enter the EU visa-free.

EU officials should agree to allow these people to visit, but in exchange for official permission from the Russian side to track their legal activities, property, bank accounts and anything else that might look suspicious. In other words, the EU should say, "If the Kremlin is claiming to fight corruption, let us try to help you!"

It's nearly impossible for the European authorities to initiate such a scrutiny of Russian officials on their own, because this would contradict EU laws protecting the privacy of personal data. But if the Russian side officially sanctioned this, it may well happen.

It would be interesting to see how the Russians would respond to such an initiative. They might balk and cite the presumption of innocence, or they might join the fight against corrupt practices. But the Russian side should have every reason to support this move because the officials who hold service passports represent the same group that has come under increasing scrutiny from Putin's anti-corruption initiatives.

Incidentally, the U.S. could eventually join this approach and track senior Russian bureaucrats in the same way.

Whatever the result of such an initiative might be, it would be better both for Western-Russian relations and for Russian domestic politics than the Magnitsky Act, which banned dozens of Russian officials from entering the U.S. and depositing their financial assets in U.S. banks.

After U.S. President Barack Obama signed the Magnitsky Act into law on Dec. 14, Russia initially responded by passing the "Dima Yakovlev law" prohibiting U.S. citizens from adopting Russian orphans. At the same time, Putin declared the fight against corruption as a part of his "renationalization" of the Russian elite. Then on Saturday, the Foreign Ministry released a blacklist of U.S. officials that it linked to human rights violations.

If the Russian side agreed to allow the West to track Russian officials (a very unlikely outcome), EU and U.S. authorities would get an opportunity to unveil the hidden details of rich and powerful Russians' lives abroad. At the same time, the Europeans would get a good reason to go further in EU-Russia visa liberalization talks. If the Russian side disagreed (which seems to be highly likely), Western policymakers would have every reason to believe that the whole Russian elite is corrupt and that Putin's initiatives to fight corruption are deceptive. And, most important, the Russian public would see that the authorities are not so much interested in easing visa rules as in keeping their financial secrets well kept.

By adopting the Magnitsky Act, the U.S. Congress voiced its willingness to fight human rights violations and corruption in Russia. The lawmakers who voted for the legislation deserve respect. But to succeed in the fight against corruption, it's much more important to engage Russian civil society in the anti-corruption effort. The West should empower the public with new information about corrupt Russian officials and businesspeople. It should also reveal evidence that the Russian government's rhetoric is false and empty. Putin's initiatives should be used to outplay him on his own field — and in turn change Russia into a normal country.

Vladislav Inozemtsev holds the international economy chair at Moscow State University's department for public governance. Yulia Zhuchkova is a visiting fellow with the Institut für die Wissenshaften vom Menschen in Vienna.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.