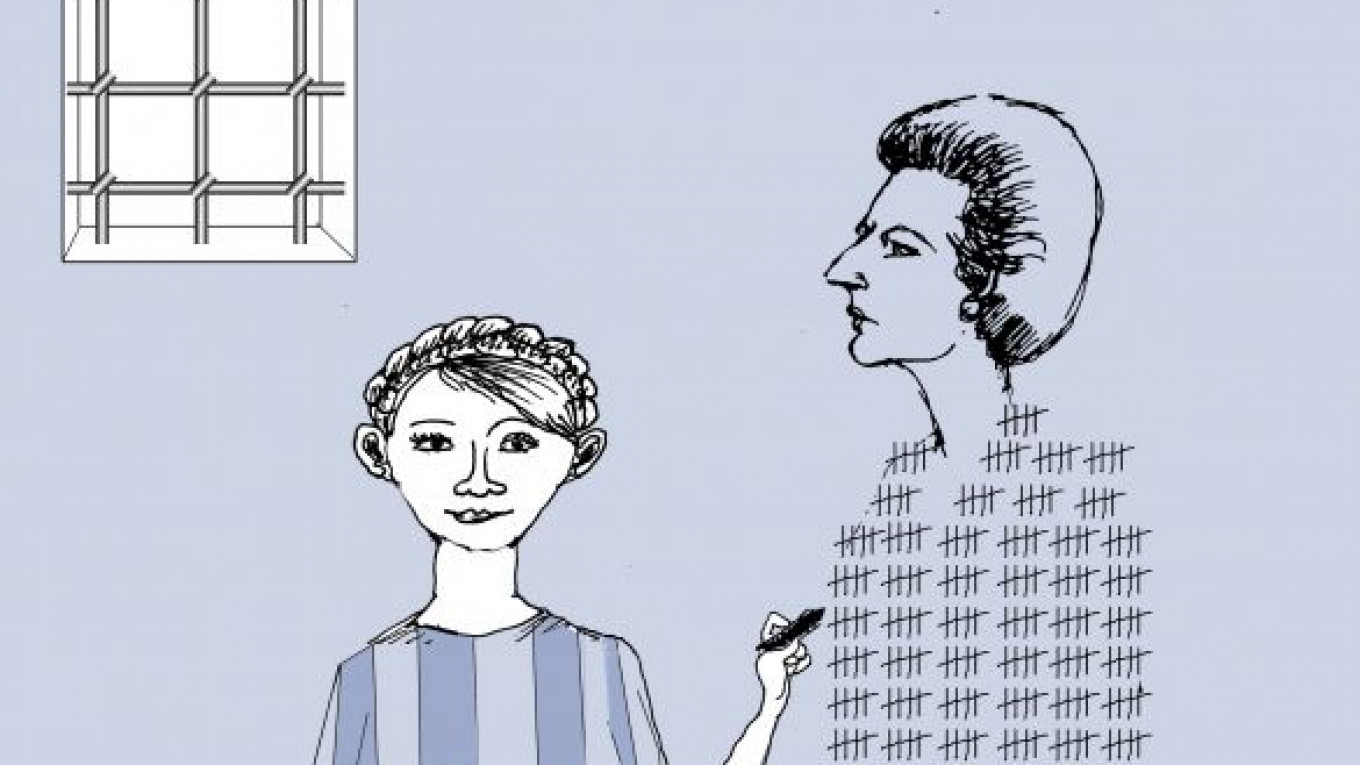

Prison is always a place of mourning. But perhaps learning of former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher's death in this place is grimly appropriate because it made me remember the imprisoned society of my youth that Thatcher did so much to set free.

For many of us who grew up in the Soviet Union and its satellites in Eastern Europe, Thatcher will always be a heroine. She espoused the cause of freedom, particularly economic freedom, in Britain and the West, and by proclaiming former Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev a man "we can do business with" at a time when almost every democratic leader was deeply suspicious of his policies of perestroika and glasnost, Thatcher became a vital catalyst in unlocking our gulag societies.

Indeed, for everyone in the former Communist world who sought to build a free society out of the wreckage of totalitarianism, the "Iron Lady" became a secular icon. Her qualities of courage and persistence provided a living example for people living in the Soviet Union and Warsaw Pact countries of a type of leadership that does not buckle at moments of political peril. I have certainly taken inspiration from her fidelity, solid principles and absolute determination to fight, and fight again, when the cause is just.

For those of us who lived in the Soviet Union, Thatcher was a heroine who stood up for freedom and helped end Soviet tyranny.

One of the true joys of my life in politics was the opportunity to have a quiet lunch with Thatcher in London some years ago and express my gratitude to her for recognizing our chance for freedom and seizing the diplomatic initiative to help realize it. Throughout my years serving as Ukraine's prime minister, I kept a quote of hers in mind: "I am not a consensus politician. I am a conviction politician." Her rigorous sense of the true duty of a politician always gave me comfort during a political struggle. After all, our duty as leaders is not to hold office but to use our power to improve people's lives and increase the scope of their freedom.

When Thatcher first expressed her belief in the potential of Gorbachev's pro-democracy reforms, I was 24, recently graduated university and was just beginning my career. There was scant hope that my life would be better than that of my mother and, more dispiriting, even less hope that I would be able to build a better life for my young daughter.

Thatcher's embrace of the cause of our freedom was electrifying for me. The great dissident writer Nadezhda Mandelstam had seen for us a future in which we could only "hope against hope." Yet here was a leader who saw for us a future of freedom and opportunity, not of squalor and moral compromise. I still shake my head in wonder that she could embrace the abandoned hope of liberation when almost no one else — not even Gorbachev — could even imagine it.

But Thatcher understood freedom because it was in her very veins. She was assuredly not for taking orders or settling for the restricted life that her society seemed to hold in store for her. In a Britain where social class still typically determined one's destiny, the grocer's daughter from the north made her way to Oxford and starred as a student of chemistry.

Then she dared to enter the exclusive male preserve of politics. When she became the first woman to be British prime minister, she fired the ambitions of countless young women around the world, including mine. We could dream big because of her example.

As a woman, Thatcher knew that she brought something unique to the corridors of power. As she said on taking office in 1979, "Any woman who understands the problems of running a home will be nearer to understanding the problems of running a country." That common-sense fusion of family values and fiscal probity set an example for every elected leader who has followed her.

Of course, I well understand that many in Britain felt left behind by the economic and social revolution that Thatcher unleashed. But the entire point of Thatcherism, as I understood it from afar, was to create conditions in which everyone could work hard and achieve their dreams. That is what I — and all of Ukraine's democrats — want for our country: a society of opportunity, under the rule of law in an open Europe, not under the thumb of cronies and corrupt oligarchs.

The record speaks for itself. Before Thatcher's premiership, Britain was widely considered the "sick man of Europe," a country afflicted by stifling regulation, high unemployment, constant strikes and chronic budget deficits. When she stepped down 11 years later, Britain was among Europe's — and the world's — most dynamic economies. As a result, we are all Thatcherites now.

Yulia Tymoshenko, twice prime minister of Ukraine, has been a political prisoner since 2011. © Project Syndicate

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.