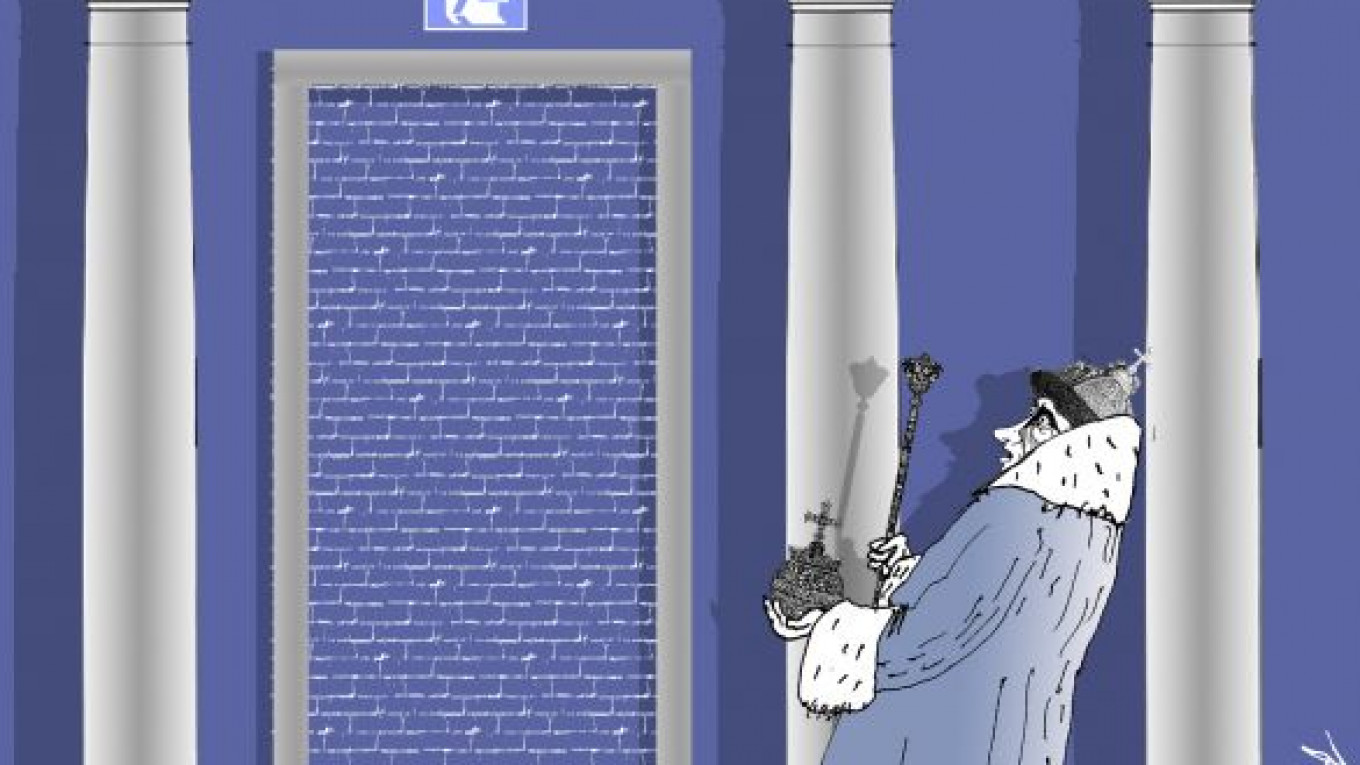

Will President Vladimir Putin ever relinquish power voluntarily?

This is one of the most important questions in Russian politics today. The entire political system is built around a single individual, and the system will undergo radical change when somebody else finally comes to power. But nobody, and perhaps not even Putin himself, knows the answer to when he will step down. In fact, history shows that entrenched leaders almost never have a plan for leaving office. They are either overthrown or die.

In the 20th century, more than 30 leaders, not counting monarchs, held onto power for more than 30 years. Of those, only a very few stepped down voluntarily or left office after losing elections. They include: Senegalese President Abdou Diouf, who lost the vote in 2000 and handed over power without challenging the election results; Vietnamese Prime Minister Pham Van Dong, who voluntarily resigned in 1987; and Singaporean Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, who handed over much of his authority to his chosen successor, Goh Chok Tong, in 1990, although he retained the title of senior minister for another 21 years.

Only failing health forced Cuban leader Fidel Castro to hand power over to his brother Raul. A brain hemorrhage left Portuguese dictator Antonio Salazar mentally deranged; although he was effectively removed from power, he still believed that he was the country's supreme leader. Former Libyan leader Muammar Gadhafi paid the ultimate price for his refusal to leave office, and many others were expelled from their countries or brought to justice.

But for the majority of the world's top dictators and authoritarians, they have little intention of stepping down. Six of them remain in power today. How do dictators manage to hold onto power so long? U.S. political scientist Bruce Bueno de Mesquita lists five rules that authoritarian leaders must follow to extend their political lifespans:

1. They must rely on as small a circle of close associates as possible. All critical decisions must be made by as few people as possible.

2. They should be able to easily replace any of them.

3. They should control the country's main source of wealth.

4. Their supporters should be amply rewarded for their loyalty.

5. All potential rivals must be ruthlessly eliminated.

Recent events in Russia tend to bear this out. Rosneft's buyout of TNK-BP might have seemed dubious from an economic standpoint, but it served to further concentrate all decisions regarding the oil sector within the tight circle of Putin's cronies. The surprise dismissal of Defense Minister Anatoly Serdyukov in November and the campaign to force out a handful of State Duma deputies serves as a reminder that nobody is irreplaceable. The systemic corruption, including that in the courts and law enforcement agencies, acts as a means of rewarding loyalty, while the growing wave of political repression intimidates potential opponents of the regime.

Dictators following these five basic rules of political survival almost always work against the interests of society. Their policies also lead to slow economic development. The exceptions are very small countries — Singapore being the best example — in which the leader requires the support of the country's entire population to retain power. In such cases, the dictator has good reason to fight corruption because it adversely affects the very people whose support he needs. But a large country like Russia requires a different strategy. It must allow the police and courts to extract bribes from the people and will compensate directly only those specific individuals whose support the regime absolutely requires.

It will be truly bad news for Russia if Putin plans to remain president for life because that would force him to follow the five rules of political survival. The fight against corruption will be announced, but nothing of substance will be accomplished. Elections will continue to be held, but without real competition. With the exception of a few military dictatorships and absolute monarchies, all nondemocratic countries feel the necessity of holding sham elections. The pressure on the media is almost certain to continue, and billions of dollars will continue to be spent on megaprojects, such as last year's APEC summit and the 2014 Olympic Games in Sochi, to try to boost Russia's image abroad at the expense of vitally needed funding for education and healthcare.

If Putin refuses to stop down willingly, society's main task will be to try to evict him peacefully and through constitutional means. To accomplish that, a great many Russians will have to band together in a display of mutual trust, civic responsibility and personal courage.

Alexei Zakharov is a professor at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow. This comment appeared in Vedomosti.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.