Although the "reset" in U.S.-Russian relations has been sapped dry, Moscow and Washington can still find ways to cooperate on combatting global terrorism, arms control and the resolution of regional conflicts. The time has come to set the agenda for such talks. Considering, however, how deeply President Vladimir Putin has taken offense with Washington over the U.S. Magnitsky Act, it would be unrealistic to expect constructive proposals from Russia anytime soon. That means the initiative should come from the U.S. side. The U.S. should take the first step because Russia is not an enemy or even a threat.

Russia wants to build a global financial center in Moscow, but it turns out that even tiny Cyprus is more of a financial center for Russian businesses and depositors than Moscow. Russia believes that it will supply Europe with oil and gas forever, but the first wave of European Union states will largely switch to buying shale oil and gas from the U.S. or switch to renewable and alternative sources of energy by 2025.

The main problem that the West currently faces with regard to Russia is not its strength, but its instability. Russia's position today is closer to that of the Soviet Union of 1988 than 1962. Given this situation, the new U.S. strategy toward Russia could be based on three fundamental policies:

The measure of wisdom for a great power like the U.S. is its ability to treat influential partners like Russia as equals.

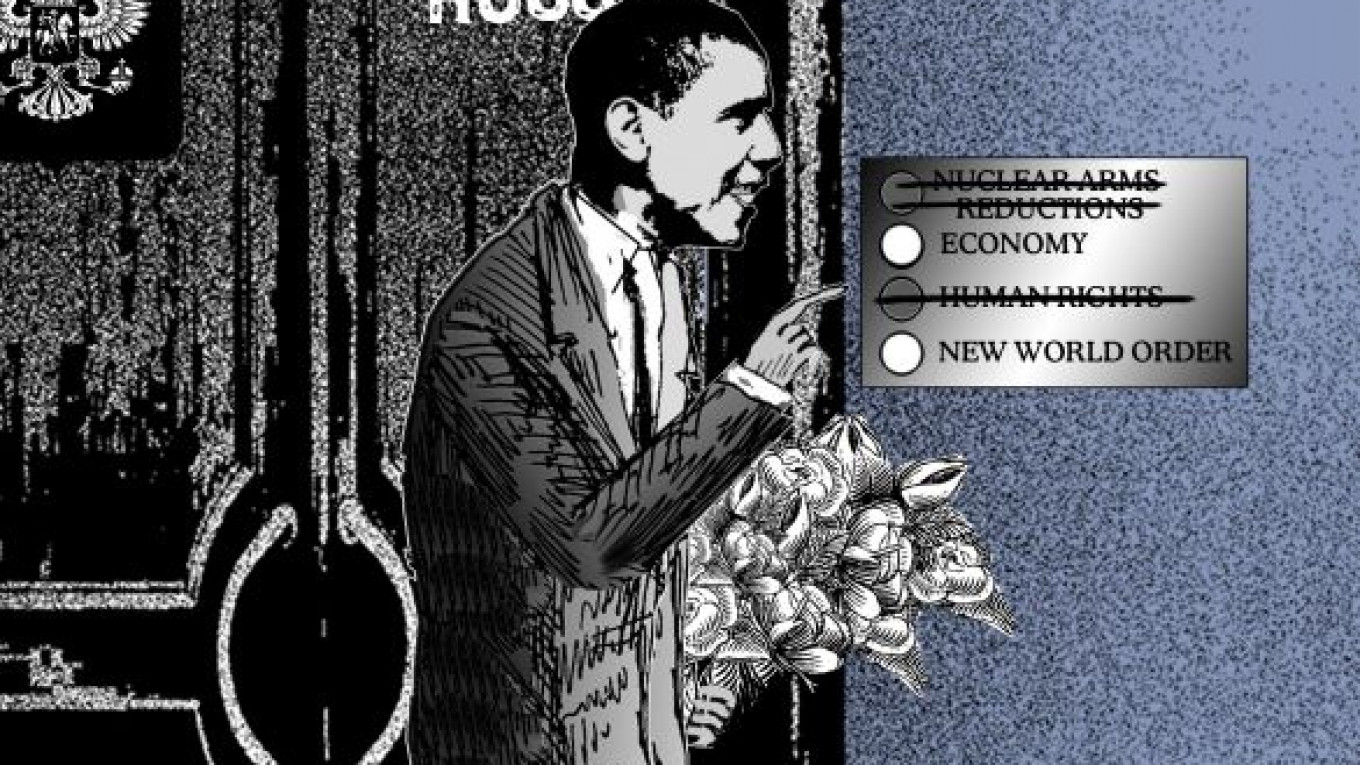

First, it would be pointless to pursue a political dialogue with Russia based solely on the old, worn-out issues of arms control and human rights. The emphasis should be shifted from politics to the economy, and Washington should be prepared to offer Russia substantial economic incentives in return for political concessions. If U.S. President Barack Obama wants Moscow to agree to major bilateral cuts in nuclear arsenals, he should promise a sharp increase in U.S. investment in Russia, cooperation on advanced technologies and willingness to sell U.S. assets to Russian companies that are interested in them, even if those companies are partially owned by the state. Washington should take the lead in engaging Russia with economic and investment initiatives to aid the development of both countries. For example, this could include a free trade zone like the one Moscow is currently negotiating with the EU and Japan. Russia is not a competitor to the United States. It is more likely an additional market for its goods and services. Washington can best achieve its military and political agenda with Russia by offering economic cooperation on any scale Moscow desires. This would be advantageous to both sides.

Second, it is fruitless to continue emphasizing human rights and other sore spots with Moscow. It would be much more productive to focus instead on general issues concerning the new world order. Russia wants its voice to be heard on the global arena. Why couldn't the U.S. work with Russia to formulate principles governing, for example, humanitarian intervention or limited sovereignty? Why not actively involve Russia in a dialogue on issues of global governance? Working together, they could define a new world for the 21st century in which the U.S., Russia and Europe would team up to retain their leadership positions in the face of rising threats from global terrorism, rogue states and competing centers of power.

Third, the U.S. has de facto disengaged from Europe politically and militarily, and it has yet to establish strong economic ties with Russia. That means Moscow and Washington should look for a new area of cooperation. One good place to start would be the Pacific Rim. Alaska, which borders Russia, currently does more trade with Ukraine than with Russia.

Just like Washington, Moscow would also like to "pivot" to the East. But in addition to China, that East should also include Japan, South Korea and, strangely enough, the United States. The U.S. and Russia could even create an alliance called the "North Pacific Treaty Organization." It sounds like a joke, but for Russia the East includes countries that for many years were part of the West. With this pivot to the East, the U.S. should become Russia's best "Eastern" ally.

Twenty-five years ago, the Soviet Union initiated perestroika and glasnost, a reform program that the U.S. supported wholeheartedly. But even after the Soviet collapse, the full potential of that bilateral cooperation was not realized because the U.S. side did not treat Moscow as an equal partner, particularly during the 1990s.

Now that Russia has recovered from the chaos, instability and poverty of the 1990s, the U.S. must take the lead in U.S.-Russian relations. Washington should start by speaking with Moscow on equal terms and with respect. The measure of wisdom for a great power like the U.S. is its ability to treat large, influential partners like Russia as equals. That approach has always been very effective in global diplomacy and international relations. The alternative — acting like a global gendarme — is not only ineffective, but it is also dangerous and destructive to global security.

Vladislav Inozemtsev is director of the Moscow-based Center for Post-Industrial Studies.

Related articles:

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.