Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev recently said: "I don't deny that my colleague, Vladimir Putin, and I are comfortable enough in talking with the U.S. But our positions differ seriously concerning certain issues. One of them is the question of weapons, including missile defense. On this topic, unfortunately, despite all our attempts to explain to the Americans that we consider the European missile defense system — in the form it is planned — as essentially aimed against Russia and its nuclear potential, our arguments have not been heard by the U.S. or by NATO." That lengthy statement provided many opportunities for comment prior to the meeting Feb. 26 in Berlin between Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov and U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry.

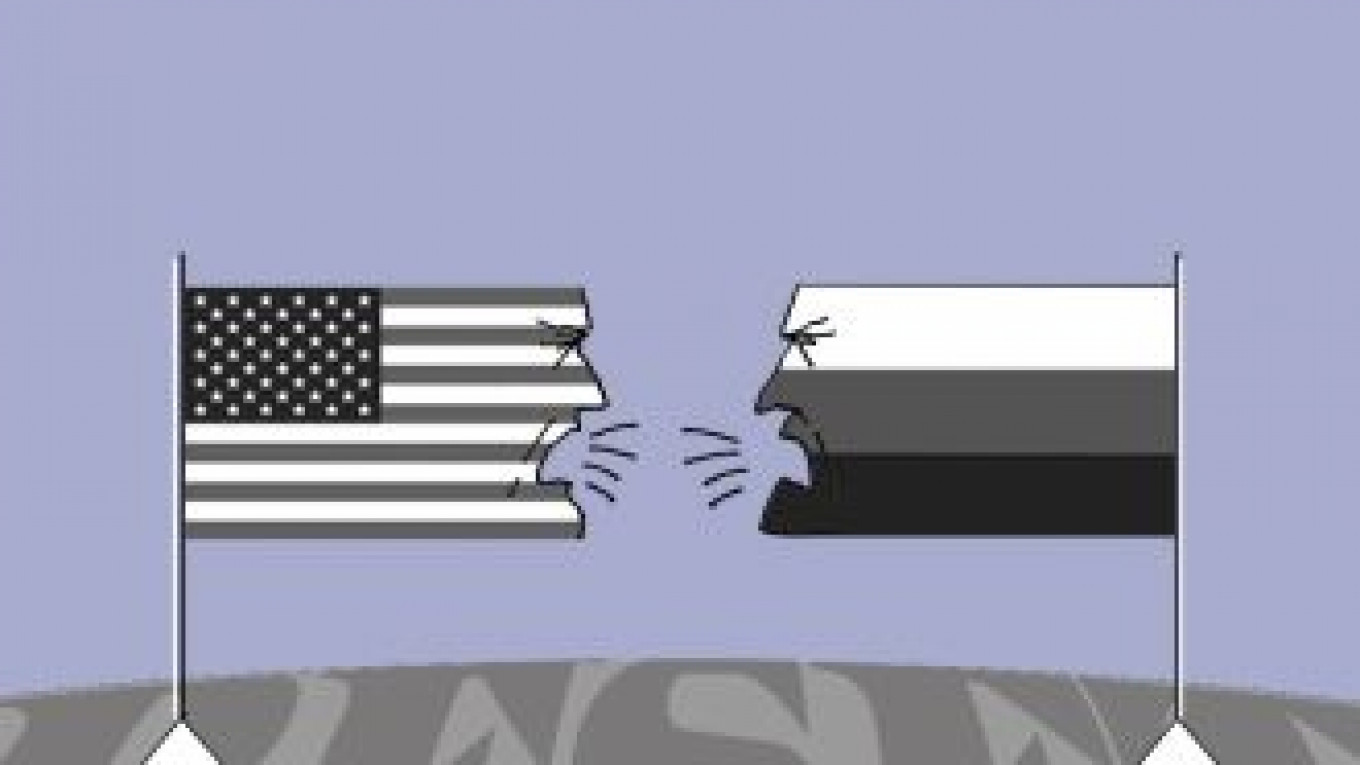

Against the backdrop of current U.S.-Russian relations, Medvedev's assertion that he and Putin are "comfortable communicating with the U.S. administration" sounds rather tongue-in-cheek — all the more so because almost nobody can be found in Washington who would say the same for the U.S. side. In my opinion, it would be more accurate to say that U.S.-Russian relations currently consist of little more than petty squabbles punctuated by moments of hysteria.

How else would you characterize the propagandistic hysteria surrounding the U.S. death of another adopted Russian child, Maxim Kuzmin? Children's ombudsman Pavel Astakhov did not even wait for the cause of death to be determined before accusing the boy's adoptive parents of murder. The issue was raised in the State Duma, and deputies observed a minute of silence in memory of the "murdered" child. U.S. Ambassador Michael McFaul was invited to testify before the parliament, but he refused to appear for the "public flogging."

Practically every state-controlled television channel ran reports on the "American killers" and featured Yulia Kuzmina, the biological mother of Maxim and his brother, Kirill, who was also adopted by the same family. Kuzmina, who had been deprived of her parental rights because of alcoholism and antisocial behavior, was cajoled out of her home in Pskov and into the public spotlight to declare before the cameras that she had experienced a change of heart and wanted Kirill returned to her. Following the taping of the program, she got drunk on the train back to Pskov, a fact duly reported by the newspapers, thus adding a grotesque turn to the scandal.

The politicization of the issue of orphans has become downright indecent. It actually required presidential spokesman Dmitry Peskov to intervene and call for everyone — including Astakhov — to tone down the emotions. Incidentally, Putin has discreetly and prudently distanced himself from the story of Maxim Kuzmin by saying that it is more important to encourage Russians to adopt Russian children than to focus on foreign adoptions.

The news on the diplomatic level is no better. No sooner had Kerry been appointed U.S. secretary of state than he spent five days trying to reach Lavrov on the phone to discuss the recent nuclear tests in North Korea. That was followed by a petty scandal over an as-yet unapproved U.S. Security Council resolution condemning a terrorist act near the Russian Embassy in Damascus that claimed more than 70 lives. When the U.S. insisted that a second point be inserted condemning Syrian government methods under President Bashar Assad, Moscow balked. It is therefore unclear why the Foreign Ministry recently hinted that Washington has shown greater understanding of the Russian position on Syria despite no outward evidence to support such a claim. On the contrary, Washington and Moscow display very little willingness to cooperate or compromise with each other on UN matters.

In the run-up to the meeting between Lavrov and Kerry, the hurried claims by Medvedev and other Russian politicians that the relationship with the U.S. was not hopelessly spoiled and that issues remained that could serve as the basis of dialogue did not sound very convincing. All the more so considering that in addition to propaganda, very concrete legal steps had been taken to dismantle recently signed bilateral arrangements that had been achieved only after great difficulty. This includes Washington's decision to withdraw from the Civil Society Working Group of the U.S.-Russia Bilateral Presidential Commission and Moscow's decision to terminate its agreement with the U.S. on law enforcement and drug control. And coming as it did soon afterward, Russia's ban on imports of U.S. meat appeared to be politically motivated.

Against this backdrop, it is difficult to believe the sincerity of claims by both sides that the two countries are still able to conduct meaningful talks on issues of mutual interest such as the nuclear programs of Iran and North Korea, achieving a settlement in Syria or cooperation on Afghanistan. Both Washington and Moscow are well aware that no real progress can be achieved on any of those questions at present. In particular, it is difficult to imagine that Moscow would agree to stiffer sanctions against Iran at a time when practically every Russian politician is insisting on the need to "oppose the United States." As for North Korea, any attempt to influence that regime seems to be a waste of effort. And regarding Afghanistan, the current arrangement, under which the U.S. transports nonmilitary cargo through Russian territory, represents the upper limit of possible cooperation. However, that might change once U.S. troops withdraw from Afghanistan and Russia's underbelly is threatened by the spread of radical Islam and drug trafficking to nearby Tajikistan and Uzbekistan — and then to Russia's border.

As for missile defense, given the current political landscape, it is difficult to imagine any arrangement that would simultaneously satisfy Moscow while not making the Obama administration look as if it were betraying U.S. national interests. The only real question is just how strong a military response Russia would make to deployment of the missile defense system in Europe, how that response would be perceived by NATO and how the situation could affect Russia's relations with the U.S. and all of Europe.

In fact, the slowly building crisis in U.S.-Russian relations was predictable. It is largely a result of trends in Russia itself, primarily the series of counterreforms that have been adopted with increasing rapidity since mid-2012. As a result, the mildest response to that process that the Obama administration might take is not continued attempts at a "reset" but a downgrading of bilateral relations. The problem is those relations have already degenerated into scandal and skirmish, as evidenced by the U.S. Magnitsky Act and Russia's decision to ban U.S. citizens from adopting Russian children.

Georgy Bovt is a political analyst.

Related articles:

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.