This weekend Moscow and St. Petersburg will host one of the biggest jazz festivals in Russia, "Triumph of Jazz," which was initiated by saxophonist and United Russia party member Igor Butman.

The festival introduced a great number of jazz newcomers over the last few years, but also gave tempting opportunities to Russian jazzmen to show their ideas and music both to wider audiences and to American colleagues. As another timely motivation to examine the phenomena of Russian jazz comes to our attention, we decided to catch up with a number of musicians to understand what is happening to the genre that had been a synonym to high treason decades before.

Stars and stripes in Russia

It is extremely difficult to catch Igor Butman, the most well-known Russian jazz musician worldwide, a week before his festival "Triumph of Jazz" starts. This year the festival, which has taken place in Moscow annually since 2001, expands to St. Petersburg.

"I basically invite those artists that seem interesting to me. My personal taste and my understanding of jazz forms the choice, and the audience, acute and knowledgeable, responds of course," said Butman, who also owns a record label and two clubs in Moscow. "We try not to repeat ourselves and always invite new musicians. However, some legendary names have been in the festival several times in different bands and acts."

This year the festival welcomes jazz-funk guitarist Lee Ritenour and his band, pianist Bill Charlap Trio and legendary drummer Roy Haynes and his Fountain of Youth ensemble as headliners.

Lee Ritenour started his music career with the Mamas & Papas, has appeared in over 3,000 sessions and has recorded 42 albums. This will be his first visit to Russia.

"I have been encountering great people all over the world who are interested in music in general, not just my music. And I have heard from other musicians that there is a great audience in Russia," he told The Moscow Times. "I will have my eyes and ears open for a dialogue with Russian people and hopefully we will enjoy spending time with each other."

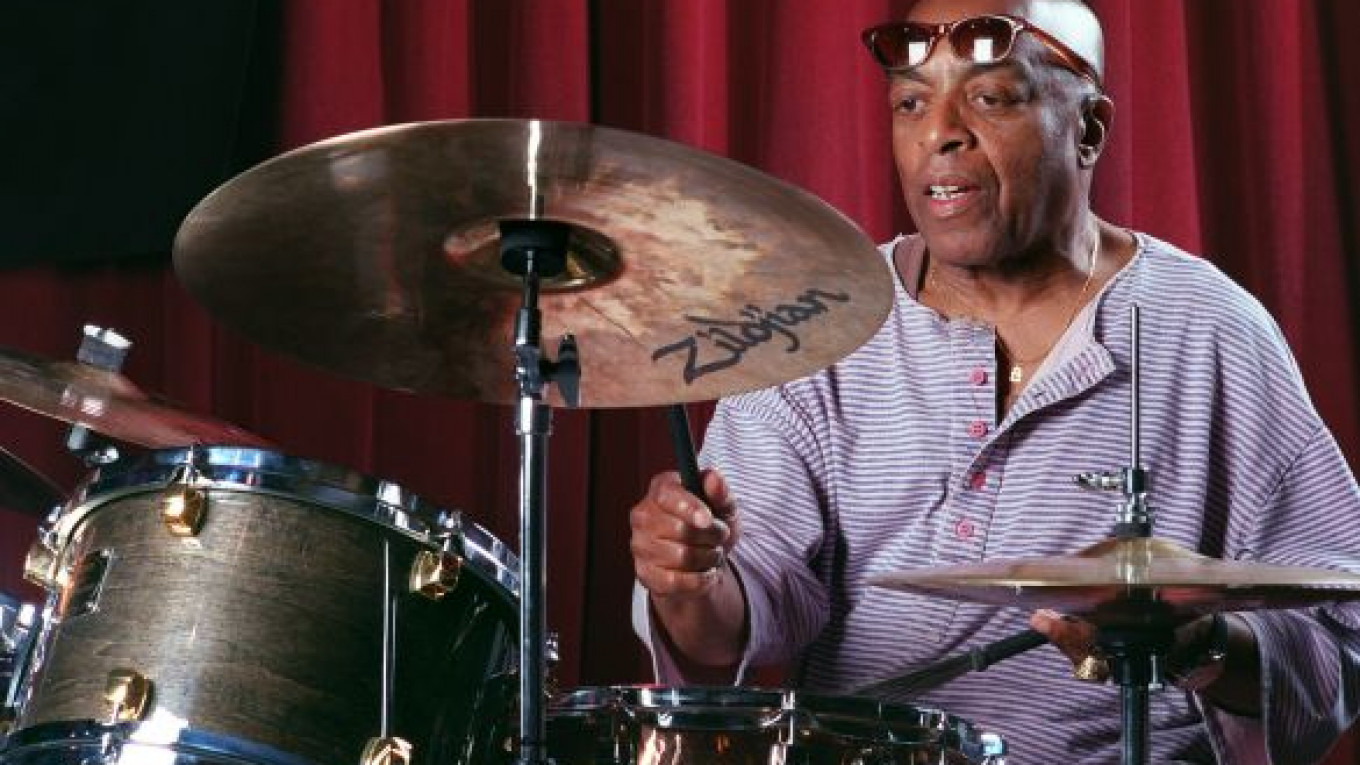

Drummer Roy Haynes, 87, is another must-see artist who will perform in Russia for the first time. He has contributed to a wide range of genres from bebop to fusion and avant-garde jazz. Nick-named "Snap Crackle" for a distinctive style of playing drums, Roy Haynes used to be a partner of the legends — saxophonists Lester Young and Charlie Parker and singer Sarah Vaughan, among others. He released as many as 26 albums as a leader, and in recent years has been touring with his Fountain of Youth band, which is made up of young musicians only, becoming Haynes' own personal source of youth.

Festivals like "Triumph of Jazz" open opportunities for Russian musicians as well. Although traditionally American ensembles form the majority of the lineup, there is always an interesting Russian addition to the festival's program, which definitely does not trail the headliners in terms of sound, originality and quality.

This year there will be two bands from Moscow: Igor Butman Moscow Jazz Orchestra, which triumphantly returned from New York City less than a month ago, and the Dmitry Mospan Quartet.

In the U.S., apart from giving shows in a number of clubs in New York, the Jazz Orchestra also checked into the studio to record its next album with past headliners of the festival — guitarist Mike Stern, bassist Tom Kennedy and drummer Dave Weckl.

In this interesting set, they recorded the originals of pianist Nick Levinovsky, the veteran of Russian jazz who repeatedly cooperates with Butman's Orchestra and currently lives in New York. Levinovsky will join the Jazz Orchestra in Moscow to perform with the Australian-based singer Fantine.

As for saxophonist Dmitry Mospan, he is also a member of the orchestra but a distinctive composer and bandleader himself. Mospan, who is turning 30 this year, started his career at the age of 14 when he was invited to join the Oleg Lundstrem Orchestra. Mospan's debut album was also recorded in New York with U.S.-based musicians and is proposed for release under the Butman Music label in 2013.

"We have put together a program of original music. It is called 'Motivation,'" Mospan said about his forthcoming appearance in the festival. "Actually there is no special story behind it. I just wanted to play some of my music, which is closer to American mainstream jazz in its sound. In terms of influences, I still think that there is something from Russian, maybe European or Oriental music, in these songs, but it happens subconsciously."

The search of the Russian accent in jazz music has become a vital topic for discussion in previous years. Jazz adepts in the business agree that there is a great number of interesting and skilled musicians who are ready to compete with American stars, but the lack of recognition of their talent by local audiences is an obstacle.

"Jazz is not in demand in Russia," said Anna Buturlina, one of the most well-known Russian jazz vocalists and an actress in the Stas Namin Theater. "The feeling of jazz is what few people have. I think it is an arduous path and you should work on yourself for a lifetime."

Buturlina, who is going to join vocalists Polina Kasyanova and Mariam Merabova on stage at the Jewish Cultural Center on Feb. 21, recently started to perform a program of famous songs from Soviet films.

"You have to come up with something original. What, precisely, is needed abroad is music with a national shift, something distinctive and produced in Russia," she said.

A rollicking history

Jazz's current humble status in Russia does not come as a surprise considering its troubled beginnings in the country.

Jazz came to Russia as long as 90 years ago. In 1922, the poet, dancer and translator Valentin Parnakh gathered an ensemble with a straight-forward name, the First Jazz Band of the Republic.

Parnakh brought a full set of instruments from Paris and tried to represent the fresh sound that had caught European clubs and concert halls a few years before. Shortly after, Parnakh's band was hired by the renowned theater director Vsevolod Meyerhold to become a symbol of the "mechanical civilization of the West."

More than two decades after jazz became popular though misrepresented in Russia, a number of orchestras and bands performed a variety of dance music under the label "jazz."

These common misuses of the style provoked the first notorious saying about it in the Soviet Union. Proletarian writer Maxim Gorky affably described jazz as the "insulting chaos of the crazy sounds," though this description actually referred to foxtrots that the writer had to endure from his son. From the official standpoint, however, jazz would assume all the blame.

Things changed during the 1950s when a younger generation of amateur musicians encountered contemporary modifications of American jazz by listening to the latest recordings of trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie, saxophonist Charlie Parker and the likes on rare records and on air of the Voice of America. There was a man responsible for a boost of interest in American music throughout Eastern European countries and Russia particularly, and his name was Willis Conover.

"We listened to Conover's program on short waves and the signal was fine," remembered trumpeter Alexander Fisher in an interview with The Moscow Times.

Fisher was born in the Far Eastern city of Khabarovsk and eventually become a member of legendary Soviet jazz ensembles, such as the Oleg Lundstrem Orchestra or Nick Levinovsky's Allegro. He now resides in Vienna.

"From Khabarovsk, Alaska and the rest of America was close at hand," he continued. "Obviously we not only listened to Jazz Hour, but also recorded the music through the noise. We also took small wireless radio sets with us when traveling, the ones that were distributed only in the Baltic region. We called them 'little slanderers'."

During the 1960s jazz bands from the Soviet republics accepted their first invitations to participate in international jazz festivals. The first festival of jazz in Moscow also took place at this time.

A number of striking live recordings had been released on the Melodiya label in the 1960s, until finally the ambiguous events in Czechoslovakia in 1968 provoked another wave of toughened control.

Being part of an endless push and pull story, jazz embodied the idea of freedom for artists born under the totalitarian regime, which has always been very strict in what to approve in art for the masses. The regime was definitely aware of the rebel character of improvising music and was on alert until the invasion of rock music.

Coined by the Soviet authorities, the popular saying, "He plays jazz today and betrays his motherland tomorrow," even nowadays seems the first association made in most Russian minds. However, things obviously changed a lot since then: though the Russian president does not play the saxophone like Bill Clinton, at least one deputy does.

Back in the Soviet years, as a sign of indulgence, "national music" had to prevail over American in the repertoire of jazz musicians. Years later, when artists had been forced to deal with total freedom and indefiniteness during the collapse of the music industry, this formula proves its effectiveness again. There are a number of notable musicians and composers who tend to rethink their national music heritage when producing something of their own.

While the forthcoming festival is a three-day precedent to get new audiences involved, the flow of improvisation never ends. Fortunately, the genre here in Russia is untouched with marketing, so the best idea is to go and listen.

The XIII International Festival Triumph of Jazz runs from Feb. 22 to 24 at the Moscow International House of Music, 52/8 Kosmodamianskaya Naberezhnaya, Tel. +7-945-730-1011, and The Igor Butman Club at Chistye Prudy, located at 16A Ulanskyi Pereulok, Tel. +7-495-792-2109.

Related articles:

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.