The recent crisis between Russia and the U.S. over the Magnitsky Act has once again provoked speculation of a new cold war in the making. The U.S. Congress led the way by passing the Magnitsky Act, which denies visas to Russian officials presumed responsible for human rights violations and freezes their assets.

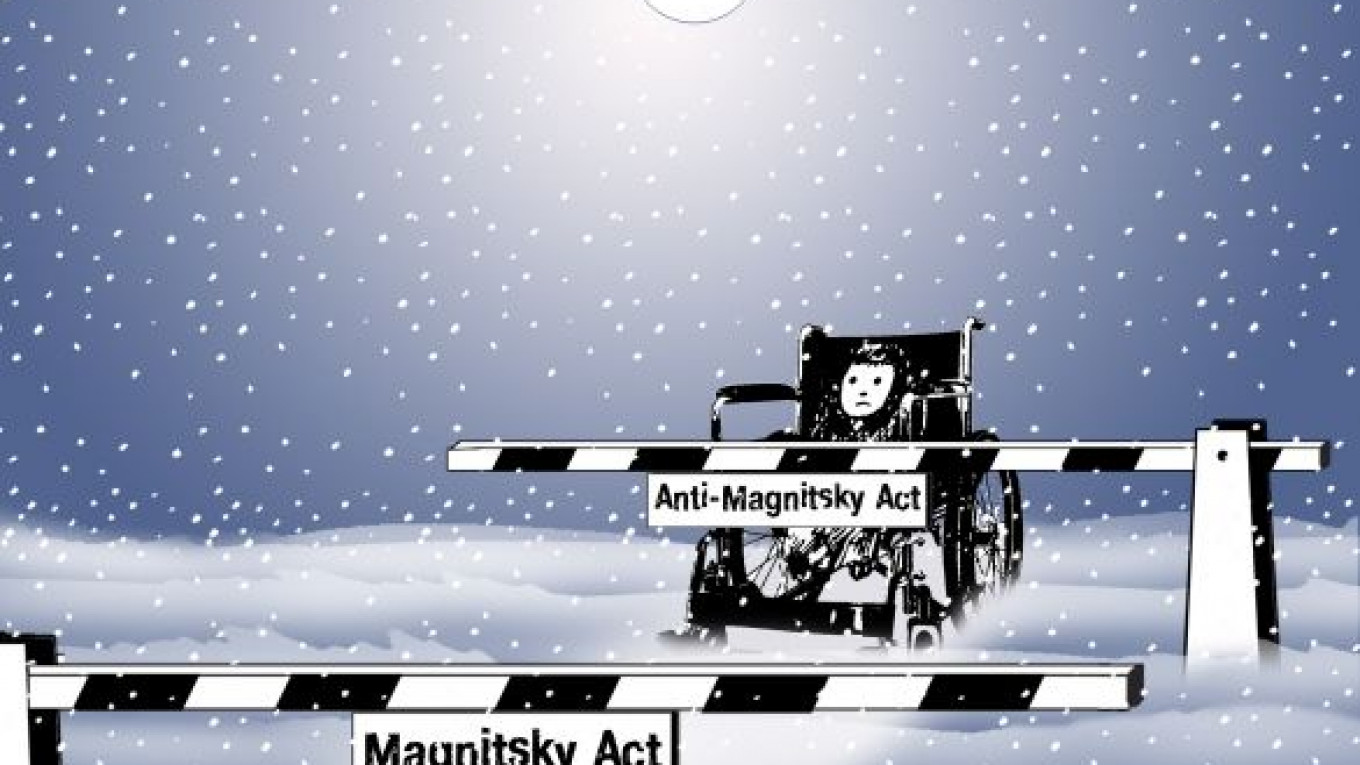

The State Duma retaliated by passing the "Anti-Magnitsky Act," which targets U.S. citizens who Russia considers to be violators of human rights. They include officials linked to torture and other violations at the Guantanamo Bay prison and judges who acquitted or gave light sentences to U.S. parents who abused or committed involuntary manslaughter against adopted children from Russia. In addition, deputies banned the adoption of Russian children by U.S. citizens.

U.S. policy toward Russia continues to be shaped by the anti-Russia lobby. It views the U.S. as the leading democracy in the world and Russia as one of the main global obstacles to this world order. The Magnitsky Act not only punishes Russian officials without any proper investigation or trial but also targets Russia exclusively as if it were the worst violator of human rights in the world. This confirms that the U.S. anti-Russia lobby's main goal is to isolate and discredit Russia, while human rights are used cynically as moral cover for Washington's geopolitical strategy against Russia. Hermitage Capital CEO William Browder, the main lobbyist for the Magnitsky Act, and Senator Benjamin Cardin, who became the main spokesman for the bill in Congress, were primarily driven by desire to humiliate and shame Russia.

As was the case under former U.S. President George W. Bush, the success of the anti-Russia lobby is predicated on a weak presidency and Russia's careless attitude toward its image abroad. U.S. President Barack Obama showed his desire to work with Russia on a number of issues of mutual importance, from missile defense to counterterrorism, nonproliferation and economic development. Obama did not initially support the Magnitsky Act, but he was all but forced to sign it because the repeal of the Jackson-Vanik amendment, something Obama overwhelmingly supported, was attached to the Magnitsky Act. In addition, there was so much support in both chambers of Congress for the bill that a presidential veto would have been useless.

At the same time, however, Russia's response was clearly foolish. For all the talk about the importance of soft power, the Kremlin chose a retaliation that will shape Russia's negative image in the West for years to come. From a reputational standpoint, penalizing U.S. adoptive parents, the overwhelming majority of whom are law-abiding, loving and caring, and punishing Russian children, many of whom are disabled and waiting for adoption, was the worst possible choice.

Russia's anti-U.S. campaign remains largely reactive. The Kremlin's retaliation by supporting the anti-Magnitsky act has little to do with human rights and is almost exclusively about protecting Russia's sovereignty. The official reaction to the Magnitsky Act may only be the prelude of other blunders to follow. The emotional side of such a reaction is frustration and anger, and it is notoriously difficult to successfully channel anger into moderate policies. Russia and the West have been through this cycle before and are still recovering from its consequences.

If European countries adopt their own versions of the Magnitsky Act or if Obama eventually agrees to expand the Magnitsky list to include senior Russian officials, the crisis in U.S.-Russian relations has the potential to escalate into a more serious and long-term cold war. As feelings of anger and frustration continue to penetrate Russian and Western societies, worse may be yet to come.

To resolve this crisis in U.S.-Russian relations, Obama needs to control the Russian agenda and not let the anti-Russia lobby dictate its terms and conditions. Obama's proposed trip to Moscow early this year should be used for a thorough assessment of a broad range of issues that separate the two countries. What is now required is an approach that avoids missionary claims and recognizes Russia's right to have its own distinct institutions and path toward development and democracy.

In addition to devising interest-based arrangements with Russia in international relations, the U.S. should develop a framework for gradually extending Russia social recognition and engaging it as an equal participant in various economic, political and cultural projects. The "reset" diplomacy never meant to serve as such framework and expired before such projects could have been identified.

At the same time, the Kremlin should learn to control its emotions and not allow them to shape the country's foreign policy. Instead, Moscow should concentrate on articulating a long-term strategy of Russia's presence in Western media markets and projecting a favorable image abroad.

Andrei Tsygankov is professor of international relations and political science at San Francisco State University.

Related articles:

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.