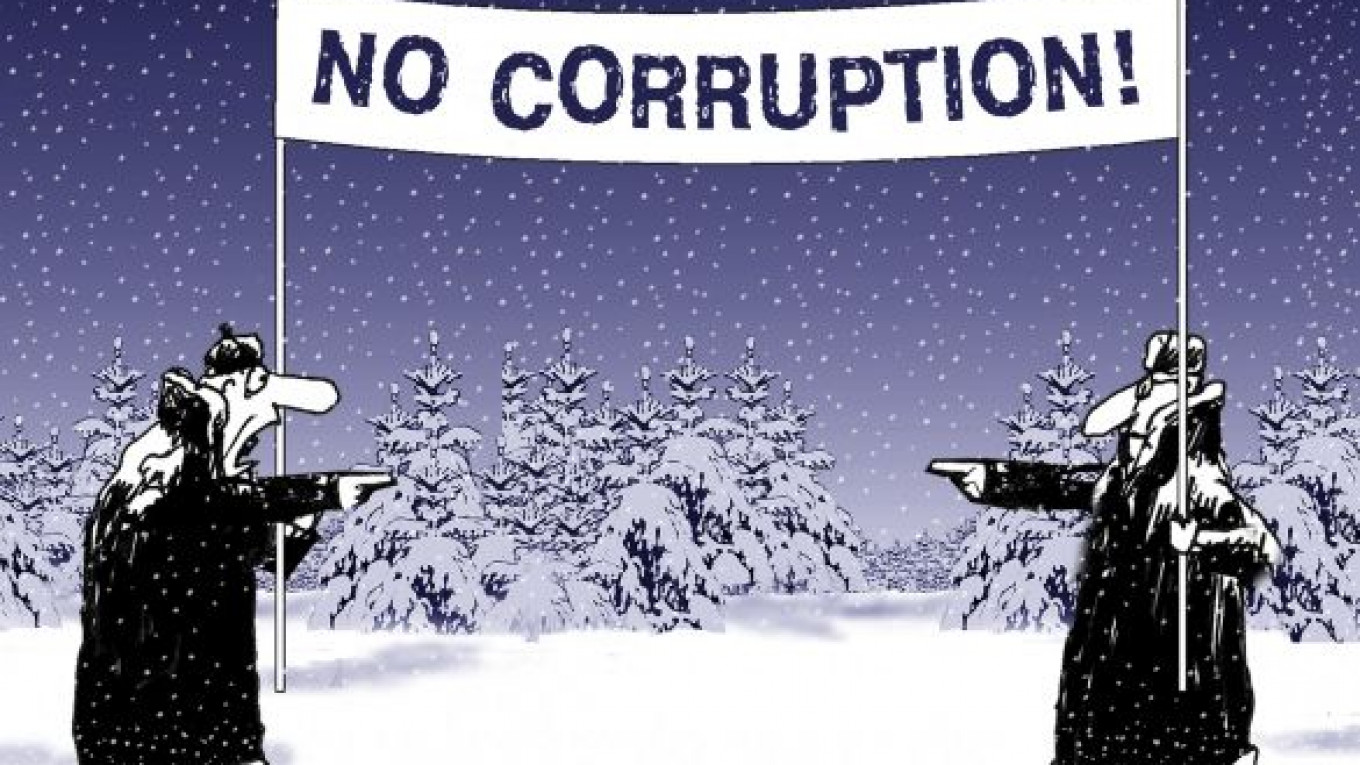

Journalists and political analysts have been speculating about whether the Kremlin's anti-corruption campaign will cause a split among Russia's ruling elite. Even if this is only a PR stunt by the authorities to co-opt the opposition's main demand, it will not produce any serious or systemic changes. But as some analysts contend, even this "innocuous" battle with corruption might prove too much for some politicians to bear. They might react by launching counterattacks of their own against the political clans assaulting them. This could trigger a chain reaction resulting in the final collapse of Putin's elite and lead to the political destabilization of the country.

Until recently, the stability of the bureaucratic elite was based on certain rules of the game that permitted corruption in return for loyalty to the Kremlin. But now faith in the old rules has been undermined, and no new rules have been introduced to replace them. It is not even clear if any new rules even exist.

Putin and other top leaders have not yet given any explanation of what is happening, while state-controlled media are almost daily "exposing" one senior official after another being caught red-handed in a police raid linked to corruption charges.

Whenever I hear talk of an impending revolt or schism among the ruling elite, I always recall my visit some years ago to a history museum in a little town in the Moscow region and the story the curator there told me. She spoke in a calm and quiet voice, like a parent might use to tell bedtime stories to a child.

"In was the late 1930s," she said. "The regional headquarters received orders from Moscow. No fewer than 3,500 people must be 'exposed' and then shot. This village received its own mini-quota from the regional center. The party leaders gathered and began discussing what to do.

"The people didn't know who to shoot because it was just a small village," the curator continued. "Everyone knew each other. The dekulakization campaign had already passed, so there were few people who could still pass as enemies of the people. At the same time, after years of civil war and Stalinism, repression had become almost habitual for them. In short, they thought and pondered and finally made an unusual decision. To avoid shooting their own friends and relatives, they stopped passing trains and used the passengers to fulfill their quota,"she concluded.

Josef Stalin's tyranny is known for another tradition. After party leaders had received orders from above as to the number of people they must condemn and shoot, they often wrote very obsequious letters back to Moscow asking for their quota on "spies, counter-revolutionaries and saboteurs" to be raised. This was an attempt to demonstrate their zeal to the authorities and their personal loyalty to Stalin. And despite the fact that these officials were themselves often taken out and shot to help fulfill the higher quota, the widespread desire to please the leadership continued.

The people who worked for this murderous system thought that the repression would never touch them. They thought that the most likely victims would be a neighbor they had betrayed, their boss or co-workers, but never them. Nobody stood up to oppose the system; they were too afraid. Many were even convinced that the system was beneficial to society.

Elements of that Soviet mindset are still alive today. It is often said that inertia and passivity are standard Russian traits, and the people's unwillingness to band together to protest violations of their civil and political rights is cited as a good example of this. Most Russians are not prepared to fight injustice with street demonstrations or displays of open resistance.

As Putin said several weeks ago, this is not 1937. But remnants of that fear — so deeply instilled in the Russian psyche — remain to this day. The same fear is held by members of the bureaucratic elite.

In the late 19th century, writer Nikolai Chernyshevsky — the intellectual father to many of the era's leading revolutionaries, including Vladimir Lenin — famously wrote that Russia is "a country of slaves — slaves from head to toe." There are already signs that the fear is waning and that people are gaining confidence in their own strength to protest the government's abuse of power, but it will take many years before that fear is completely gone.

There is at least some comfort in knowing that 2012 is, indeed, not 1937 and that if history repeats itself, it does so in the form of a farce.

Georgy Bovt is a political analyst.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.