Britain definitely had a thing for Russian culture in November. And there was pretty much something for everyone. The month's events involved the works of numerous Russian film directors, a touring production from a venerable Moscow playhouse, a dramatization of a Russian political and legal scandal, an art exhibit and an exhibit of photographs of Russian theater.

Last week, The Moscow Times reported on "Gaiety Is the Most Outstanding Feature of the Soviet Union: Art From Russia," an exhibit of 18 artists at the Saatchi Gallery. But there was a lot more than that going on.

Andrei Konchalovsky, the film and theater director who began his career 50 years ago apprenticing with the great Andrei Tarkovsky, belatedly celebrated his 75th birthday with a retrospective festival of his films in numerous cities, a lecture at Oxford and a master class at Cambridge. Among the films shown were "The Story of Asya Klyachina" (1967), "Uncle Vanya" (1970), "Sibiriade" (1979), "Gloss" (2007) and "The Nutcracker" (2010). Also included were some of the director's Hollywood films, including "Maria's Lovers" (1984), starring Nastassja Kinski, Keith Carradine and Robert Mitchum, and "Runaway Train" (1985) starring Jon Voight.

Alongside Konchalovsky, the Russian Film Festival in London presented the works of over two dozen contemporary directors, ranging from documentaries and experimental works to mainstream entertainment. Cherry-picking titles from a complete schedule published on the Academia Rossica website, I would highlight Vasily Sigarev's "To Live," Alexei Balabanov's "Me Too," Pavel Lungin's "Conductor," and Boris Khlebnikov's "'Til Night Do Us Part."

Meanwhile, across town at the Noel Coward Theatre, Moscow's Vakhtangov Theater was in residence for six days with its award-winning production of "Uncle Vanya." As Kate Mason wrote on the One Stop Arts website, "This 'Uncle Vanya' is not the cosy sort of Chekhov that made his plays British favourites, with their tea, petty conversation and the suffocating ennui of the rural bourgeoisie. In director Rimas Tuminas' production, there is no samovar and not a lace doily in sight."

That said, the responses appear to have been split. Even those leaving comments beneath a negative review by David Nice on ArtsDesk.com engaged in heated exchanges, some finding the show "self-indulgent" and "unforgivably dull," while others found it "incredible."

"Why is it that people who review Chekhov seem incapable of accepting anything other than realism?" this latter, unidentified commentator asked. "The Arts Desk must get someone else — I won't trust this reviewer ever again!"

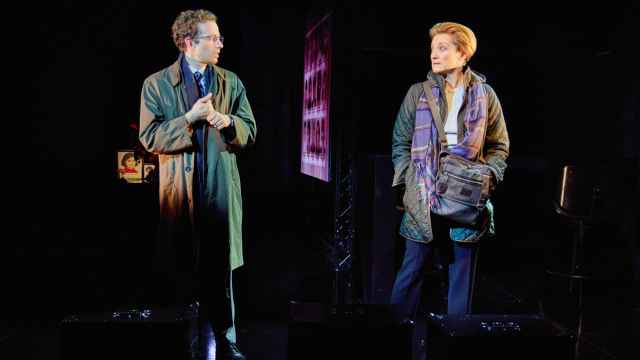

Noah Birksted-Breen has made herculean efforts over the last seven years to bring cutting-edge Russian theater to London. His Sputnik Theatre has staged English-language, and sometimes world, premieres of works by important new playwrights Yury Klavdiyev, Natalya Moshina, Yaroslava Pulinovich and others. Over the last three weeks of November, he presented his latest, a rendition of Yelena Gremina's politically charged docudrama "One Hour Eighteen Minutes," at the Diorama Theatre in London.

"One Hour Eighteen Minutes" tells the story of the demise of Russian muckraking attorney Sergei Magnitsky in prison. It is cobbled together from interviews with, and press reports about, many of the people who were around Magnitsky at the time that he was "allowed to die" from pancreatitis in November 2009. Gremina put together her first version of the play in early 2010, shortly after Magnitsky's death. For the recent London run, Birksted-Breen used an updated and expanded text which is premiering in Moscow now.

Many reviewers and commentators have pointed out the play's importance as an act of civil awareness and social conscience. Tom Stoppard, speaking after seeing "One Hour Eighteen Minutes" on Nov. 20 pointed out that without the efforts that have been made to keep Magnitsky's name in the news, "this case would have been forgotten, it would have been a dim memory."

Photographer Ken Reynolds opened an exhibit, Russian Theatre in Performance, of his extraordinary photographs at the Pushkin House in London in mid-November. As explained in promotional material on the Pushkin House website, it features shots "drawn from complete rehearsals and actual performances, never from photo calls; invariably taken from just one position, using very fast black and white film, and never using flash."

Reynolds has a genius for textural images, and it shows in the best of his photos, which use the grain of his ultra high-speed film to capture the soul of theatrical performance. His photos often allow us to glimpse deeply expressive, frozen action — actors flying, spinning, falling, gasping or laughing. The current exhibit presents images of productions by Lev Dodin, Kama Ginkas, Genrietta Yanovskaya, Dmitry Krymov, Boris Yukhananov and nine other prominent directors. "Dodin and Ginkas are the most strongly represented," the photographer wrote to me in an e-mail. The exhibit continues through Dec. 21.

Finally, in a semi-non sequitur, I am pleased to report that Georgian director Robert Sturua has been reinstated as the artistic director at the Rustaveli Theater in Georgia. There is a British connection here not only because Sturua has often worked in London, but because he is one of the featured directors in the Ken Reynolds exhibit. The Russian connection is that Sturua has worked even more in Moscow than in London. Since being fired from the Rustaveli in August 2011 following a flap with president Mikheil Saakashvili's administration, Sturua has been the chief director at Moscow's Et Cetera Theater.

According to a report on Lenta.ru, Sturua was also named the head of his own small theater, which he will open in January with a production of Terrence McNally's "Maria Callas."

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.