When a childhood friend said he was thinking of not returning to Russia after a concert tour abroad in 2000, Sergei Magnitsky gave him a copy of "Brat 2," a popular movie released earlier that year, in the hope of dissuading him from emigrating.

"Brat 2" tells the story of a justice-seeking rebel, played by the actor Sergei Bodrov Jr., who goes to the United States to rescue his brother from gangsters. He quickly becomes disillusioned with the country, where he thinks people "seek truth in money" and, after helping his brother, returns home to Russia.

Described as "a very Russian man" by friends, Magnitsky also was not impressed by London's narrow streets when there on business, and he enjoyed traveling around Russia. He once made a trip to Odessa, where he was born.

"The word 'patriot' might sound vulgar, but he loved Russia," said Tatyana Rudenko, Magnitsky's aunt, who was close to her nephew throughout his life.

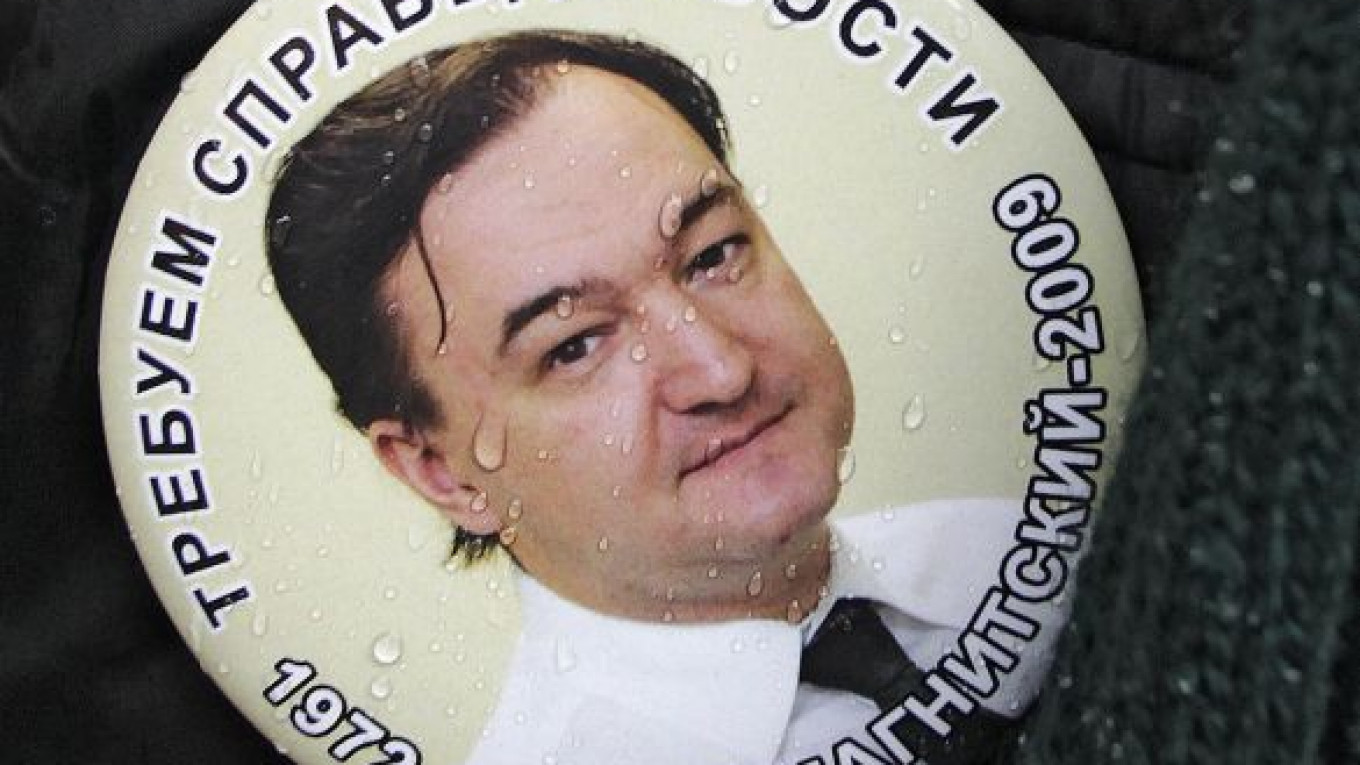

Magnitsky, a senior auditor and tax attorney for the Moscow-based law firm Firestone Duncan, died on Nov. 16, 2009, in a Moscow prison, where, according to a Kremlin human rights council investigation, he was badly beaten by guards shortly before he died.

A criminal investigation was carried out, but no senior prison or police officials have been prosecuted in connection with his death.

On Nov. 16 of this year, the third anniversary of Magnitsky's death, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the Sergei Magnitsky Rule of Law Accountability Act, which seeks to punish Russian officials implicated in his death as well as other Russian officials linked to human rights abuses.

In Magnitsky's home country, senior government officials have lambasted the U.S. legislation as an "insult" and said Russia will retaliate if the act becomes law.

The bill is expected to be passed by the U.S. Senate and signed into law by President Barack Obama by the end of the year.

Upon his death, Magnitsky became a symbol of injustice around the world. But his life reveals a man who was in many ways ordinary — a husband and a father, a diligent auditor and tax lawyer, a helpful colleague and a devoted friend, who felt compelled to fight a state machine he had trusted his whole career.

Pressure in Prison

Magnitsky's saga behind bars began on Nov. 24, 2008, when he was arrested in his Moscow apartment by investigators.

He was accused of having assisted William Browder, the head of private equity fund Hermitage Capital, a Firestone Duncan client, in committing tax evasion. Prosecutors have since alleged that Magnitsky and Browder avoided paying 522 million rubles ($16.8 million) in taxes by falsifying tax declarations and illegally using tax breaks intended for companies employing disabled people.

A month before his arrest, Magnitsky had presented evidence against two police officials, implicating them in a tax fraud scheme in which Magnitsky said $230 million was stolen from the Russian budget. Magnitsky said he had been "taken hostage" by investigators because of this evidence.

Magnitsky said police officials had used Hermitage Capital documents and seals seized in a 2007 raid to steal Hermitage's investment companies, which then requested and received the $230 million tax refund from the state on the basis of fraudulent information.

When Magnitsky was arrested, his friends worried about how he would hold up in Moscow's notorious pre-trial prisons, known for crowded cells, lethal infections and brutal personnel.

Under what he said was pressure by investigators to recant his testimony against them and to implicate himself and Browder, Magnitsky was moved between four different detention facilities and between countless cells at the jails.

A voracious reader, Magnitsky sought relief in books, though they were often hard for him to come by. Rudenko said that Magnitsky was once brought some old women's magazines with articles about dieting. At one point he managed to get ahold of Leo Tolstoy's novel "Resurrection," which depicted the squalid conditions of Russian prisons at the turn of the 20th century.

"Nothing has changed — it has even become worse," Magnitsky wrote to his lawyer after reading the book.

But Rudenko said her nephew tried to hide his suffering from friends and family members when writing to them from prison.

She recalled that in one of his letters, he referred to a picture of an imperial palace built by Catherine the Great and later used by Peter the Great that was printed on an envelope Rudenko had sent him. "He said it would be a great place to visit," she said.

In another letter, Magnitsky gave her advice on creating a children's book she wanted to make at a publishing house where she worked as a graphic artist.

Despite stark differences between Magnitsky and the other inmates, Rudenko and Magnitsky's friends said he was able to get along with them, even helping them with their legal appeals.

"He could find a common language with anyone, a homeless person or a professor," Rudenko said.

Magnitsky's mother, Natalya Magnitskaya, told the BBC Russian Service last year that his family had asked Sergei in letters about his health, which quickly deteriorated in the harsh prison conditions, but that he had not complained. She said prison authorities allowed her just one visit with her son during his time behind bars.

Magnitsky was more forthcoming about his prison life in a diary he kept, in which he described conditions in the Butyrka jail. In one entry, he wrote about being punished for complaining about such mundane things as a lack of hot water in his cell.

"The reaction was immediate. On the same day I was transferred to cell N59, where conditions were much worse," he wrote.

His diary was later used for a macabre play titled "An Hour and 18 Minutes" done by Moscow's Teatr.doc theater. The name of the play refers to the time he spent in an isolation cell in the Matrosskaya Tishina prison, where he died in severe pain. The authorities initially blamed his death on a pre-existing health problem.

Over the year he spent in detention, Magnitsky wrote a number of lengthy appeals for the authorities to uphold his rights, and he maintained his innocence, holding out hope that he would be released.

"He knew the law, so he felt sure of himself because he understood that he had broken no laws. He had an idealistic approach, which led to his death," Rudenko said.

Jamison Firestone, managing partner at Firestone Duncan and Magnitsky's boss, said that Magnitsky had been given opportunities to leave Russia — as other lawyers for Hermitage did — but had refused.

"Sergei could have left. He had many offers of help to get out. He simply believed in his country and his government and never thought he had a reason to flee," Firestone said.

Childhood friend Roman Mamayev, a noted Russian accordionist who received the copy of "Brat 2" from Magnitsky, said Magnitsky didn't think that leaving Russia would solve any problems.

"He gave me that movie and said, 'You might change your mind if you watch it,'" Mamayev said.

Mamayev ended up staying in Russia, although he said it wasn't only the movie that kept him here.

Life in Nalchik

Sergei Magnitsky was born on April 8, 1972, in Odessa, Ukraine, where his parents were attending the Polytechnic Institute. But he grew up mostly in Nalchik, the capital of the North Caucasus republic of Kabardino-Balkaria.

Sergei's father, Leonid Magnitsky, and his wife, Natalya, both worked for the electronics industry, a field closely connected to the defense industry, in Nalchik and in various other parts of the Soviet Union, including in Kazakhstan and Ukraine. Sergei Magnitsky's mother later taught computer classes to children.

But Sergei Magnitsky was especially close to his stepfather, a former Soviet naval officer whom Natalya Magnitskaya married when the boy was 12 years old, after divorcing her first husband.

Mamayev, who remained close to Magnitsky since childhood, said he was first drawn to Sergei after watching him surrounded by other children during recess at school. Magnitsky gained the nickname "Magnet," a shortened version of his last name.

"He was able to attract kids because he could explain the essence of things," Mamayev said.

Rudenko, Natalya Magnitskaya's sister, who spent a lot of time with Sergei and his mother in Nalchik, said that the young Sergei was a good student but "not a nerd."

She recalled being impressed with the boy's intelligence. As an example, Rudenko cited a drawing Sergei made of a pirate, with long curls, an eye-patch and two dark lines for a mustache, along with a speech bubble that said, "Why am I like this?"

"I was impressed with how a little boy could draw this picture. It wasn't a simple drawing. It made you think," said Rudenko, who keeps a copy of the drawing on her wall.

In school, Magnitsky combined a devotion to history books and scientific magazines, including his favorite, the popular Soviet publication Science and Life, with an interest in international economics.

Mamayev said Sergei would take a routine task, such as doing a report on Namibia, and put a lot of effort into it, finding interesting details about the country's development. "I think he was the first person who taught me the meaning of GDP," Mamayev said.

As children, the two boys liked to play Monopoly — although the original board game, being a celebration of capitalism, was not available in the Soviet Union. Instead, they made a copy by hand.

Magnitsky's interest in economics and finance led him to apply to the accounting department of the well-regarded Plekhanov Institute in Moscow, a choice that disappointed his family.

"We didn't understand his choice at first because we thought this profession was completely uninteresting," Rudenko said. She explained that being an accountant in the Soviet Union was considered tedious work and therefore not something they considered suitable for a bright student like Sergei.

His mother had wanted her son, who graduated from school with high marks, to enroll in the prestigious Moscow State University department of math and physics.

But Mamayev said Magnitsky had great respect for economics, believing it to be of vital importance in the world.

"He always told me to look at economics, saying that it was the cause of everything," Mamayev said.

'Soft-Spoken and Thoughtful'

Magnitsky's accounting education helped him secure his first job, in 1992, at Ernst & Young, which had opened an office in Moscow three years earlier. He started working for the international auditor while still a last-year university student.

During the tumultuous reforms of the late 1980s enacted by Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, Magnitsky followed politics but was not interested in getting involved in the government, Rudenko said.

Magnitsky held conservative values and went against certain societal trends, his aunt said. In the early 1990s, as many people began avidly reading the literature of Alexander Solzhenitsyn, whose books were banned for years, he told his aunt that he wanted to finish reading Lev Tolstoy's works first.

After getting his first job, Magnitsky began wearing smart suits during business hours, but friends said he didn't change much from the person he had been before.

In 1995, Magnitsky left Ernst & Young to join Firestone Duncan, a small law firm started in 1993 by American attorneys Jamison Firestone and Terry Duncan.

Duncan was killed in October 1993 during a bloody standoff between Interior Ministry troops and demonstrators at the Ostankino television tower, part of the constitutional crisis that year that pitted President Boris Yeltsin against parliamentary leaders. Witnesses said Duncan was trying to rescue people from gunfire.

"They probably would have liked each other," Firestone said about Duncan and Magnitsky. They were "equally fierce about honesty and fairness, though with totally different emotional characters. Terry was emotional and Sergei soft-spoken and thoughtful."

Firestone said he didn't remember the details of how Magnitsky first came to the company but said the job was a chance for him to advance faster than he could have at Ernst & Young.

Magnitsky was a licensed auditor but worked mainly as a tax attorney, according to Firestone. "He hardly did any audits. He advised clients on how to structure their businesses efficiently and how to comply with Russian tax law," Firestone said.

Former colleagues said Magnitsky was hardworking and a mentor who trained a generation of tax consultants and auditors.

"He wasn't involved in politics, he wasn't an oligarch, and he wasn't a human rights activist," reads a tribute to Magnitsky written by colleagues. "He was just a highly competent professional — the kind of person whom you could call up as the workday was finishing at 7 p.m. with a legal question and he would cancel his dinner plans and stay in the office until midnight to figure out the answer."

In his free time, Magnitsky liked to listen to classical music — which he warmed up to as an adult, having been a fan of Western rock bands like Kiss and Slayer in his youth — and kept a set of CDs near his desk at work.

"He used to get a season ticket each year to attend concerts with his family," Firestone said. "It was the only time he ever left the office early."

Rudenko said one of Magnitsky's favorite groups was the Alexandrov's Army chorus, part of his fascination with military history.

"I thought from my childhood that nothing more horrible than this chorus could possibly exist," Rudenko said. "But then when I heard them sing live, I was blown away."

Magnitsky lived in several different rented apartments in Moscow, some very small ones, before being able to buy an apartment for his family.

Rudenko said that while doing renovations in his newly bought apartment, Magnitsky kept its original windows intact, saying he wanted to preserve the historical interior.

Magnitsky and his future wife, Natalya Zharikova, dated in high school but broke up, and Zharikova married another man. The two began seeing each other again in Moscow, however, and Zharikova divorced her husband, with whom she had a son. After the marriage — another decision Sergei's parents opposed because Zharikova already had a child Sergei would need to support — the couple had a second son of their own. One boy is around 8 and the other is in his early teens.

Mamayev said the atmosphere at the family's three-room apartment in the Chistiye Prudy neighborhood in central Moscow was sometimes friendly, although he recalled that Magnitsky could be strict with his sons. He remembered Sergei becoming angry on one occasion when one of his sons used the English word "juice," telling him to use the Russian word "sok" instead.

He could be stern with his friends as well, such as when giving someone a loan.

"He might give you money, but he would lecture you on how to spend it properly," Mamayev said.

Magnitsky's widow keeps a low profile, and family friends said she does not give interviews.

Rudenko said the family had a cat named Fedot that Sergei asked about in his letters from prison. The cat died exactly a year to the day after Sergei's death.

The Hermitage Case

Jamison Firestone, the former boss, said Magnitsky's involvement in the tax embezzlement case that led to his death began slowly.

At Firestone Duncan, Magnitsky worked as one of the external lawyers for the Hermitage Fund in Moscow.

The Hermitage Fund is part of Hermitage Capital Management, an international investment firm co-founded by William Browder, who was one of the largest foreign investors in Russia in the 1990s and 2000s, putting billions of dollars into Russian companies. Browder, who gained a reputation as a crusader for shareholder rights, was refused entry to Russia in November 2005 on the grounds that he posed an unspecified threat to national security.

In June 2007, Moscow police raided the offices of Hermitage and Firestone Duncan, saying they were investigating whether a firm with suspected links to Hermitage Capital had underpaid millions of dollars in taxes.

Magnitsky began to investigate what was going on.

"First he just tried to figure out the tax case and challenge it and try to get back all the documents that were taken that had nothing to do with that case," Firestone said.

In July 2008, Magnitsky filed a criminal complaint with various government agencies, alleging that he had found evidence that Interior Ministry officials were involved in requesting and receiving a fraudulent $230 million tax rebate using documents stolen during the raids of Hermitage Capital and Firestone Duncan.

Four months later, Magnitsky was detained on suspicion of tax evasion, charges he denied and said were fabricated to put pressure on him to withdraw his accusations against the Interior Ministry officials.

The tax evasion case against him has continued to move forward even after his death three years ago, and it was passed to a Moscow court for trial last week.

Meanwhile, Firestone said he recently received a letter from the Interior Ministry saying no evidence had been uncovered to support Magnitsky's criminal complaint against police officials.

Justice for Magnitsky

While an independent Kremlin human rights council investigation found in July 2011 that Magnitsky had been badly beaten by prison guards shortly before his death, prison officials have insisted that he was the victim of neglect by prison doctors.

Some of the officials implicated in creating harsh conditions for him in prison — including Oleg Silchenko, who handled the Interior Ministry investigation into his death — have received promotions and awards. A week before the one-year anniversary of Magnitsky's death in November 2010, the Interior Ministry conferred upon Silchenko the honorary title of best police investigator.

Dmitry Kratov, the deputy head of the Butyrka prison where Magnitsky was held before being transferred to Matrosskaya Tishina, is the only person currently on trial over his death. He is accused of negligence, a charge he denies, and faces up to five years in prison if convicted.

Kratov said in July that Magnitsky could have died from "extreme stress."

Magnitsky's friend Mamayev recalled seeing Sergei two weeks before his arrest. They ate at a Ukrainian restaurant, teased each other, and sang loud songs while walking home.

Mamayev, who began weeping as he recounted seeing Magnitsky for the last time, said he learned about his death while on a concert tour in Nalchik.

"The news killed me. He was a very special man," he said. "To say that he was my brother does not even come close to describing him."

Related articles:

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.